Ancient Writing Materials

Contents: Introduction *

Papyrus *

Parchment *

Paper *

Clay *

Wax *

Other Materials **

Reeds, Quills, and other Writing Instruments

* Ink

* Other Tools Used by Scribes **

Technical Terms Used in Describing Writing

Introduction

Biblical manuscripts, with a few minor exceptions such as verses written on amulets and pots, are written on one of three materials: Papyrus, Parchment, and Paper. Each had advantages and disadvantages. Parchment (treated animal skins) was by far the most durable, but also the most expensive, and it's difficult to get large numbers of sheets of the same size and color. Papyrus was much cheaper, but wore out more quickly and, since it is destroyed by damp, few copies survive to the present day, except from Egypt (and even those usually badly damaged). Moreover, heavy usage eventually made it hard to obtain. Paper did not become available until relatively recently, and while it was cheaper than parchment once paper mills were established, the mills had high overhead costs, so they were relatively few and far between; paper was by no means as cheap in the late manuscript era as today (when paper is made from wood pulp rather than rags).

Although we usually will refer to these three types of surfaces as "writing materials," in some contexts, the term "substrate" is used. The difficulty with this term, of course, is that it has a very different meaning in other contexts.

The following sections discuss the various types of ancient writing materials and how they were prepared.

We might note that, once the material was prepared, pages were prepared for writing in much the same way no matter whether they were of parchment, papyrus, or paper: The quires were laid out and the pages pricked and ruled (that is, the pages were measured and holes pricked at regular intervals and grooves scored into the pages using a leaden or sharp point, so that the scribe would have a straight line reference). Ruling styles varied from region to region (e.g. in western Europe, pages were ruled all the way across a folio before being folded; in Britain, they were folded and then ruled page by page; some schools ruled both sides of the page, others only one; some scribed ruled every line, others alternate lines or even, in some Egyptian writings, every third line) and very slightly from material to material (only one side of a papyrus sheet needed to have the lines ruled, since the fibre gave a parallel reference on one side -- and as a result, some papyri do not seem to have been ruled at all, although we observe the pricked holes for ruling in some manuscripts, including 𝔓66). But the general picture of how pages are made ready for writing is the same.

An interesting note about scrolls is that the pricking and drawing of borders was sometimes done before the individual sheets were combined into a roll; there are some with border elements that do not align.

Papyrus

The earliest relatively complete description of how papyrus was prepared comes from Pliny's Natural History (xiii.11f.): "Papyrus [the writing material] is made from the papyrus plant by dividing it with a needle into thin [strips], being careful to make them as wide as possible. The best quality material comes from the center of the [stalk]," with lesser grades coming from nearer to the edges. The strips are placed upon a table, and "moistened with water from the Nile... [which], when muddy, acts as a glue." The strips are then "laid upon the table lengthwise" and trimmed to length, after which "a cross layer is placed over them." These cross-braced sheets are then "pressed together, and dried in the sun."

This statement has its questionable parts -- e.g. there is no evidence that water from the Nile as such can be used as a glue, though it is possible that some sort of glue could be made from some sort of soil found by the Nile. (An alternative possibility that I have not seen elsewhere is that perhaps Nile water was used as a sizing agent to smooth the surface of the papyrus -- it might perhaps have carried a suitable sort of clay. But this is only a wild guess.) Pliny and Varro also state that papyrus as a writing material was unknown in the Greco-Roman world before Alexander the Great, which seems to be false (note the existence of the word χαρτες for papyrus, which became charta in Latin; there seem to be records of papyrus being used well before Alexander), and deny that parchment existed as an alternative until still later than that, which is patently false. Nonetheless the basic description is certainly true: The stalks were divided into strips, braced by having another layer of strips stuck across them perpendicularly, pressed, and dried.

The details are not at all clear. For example, some have argued that the glueing did not involve actual glue -- that the fibres adhered to each other naturally if enough pressure was applied while they were still fresh. And although most have suggested that the pressure was applied by presses, some believe the sheets were hammered to make them bond. And, finally, although most think the papyrus root was sliced, some have suggested that it was peeled.

It should be noted that the core of the papyrus plant was somewhat triangular, so it is not certain whether the core was sliced in parallel lines or triangularly, i.e.

/\ /\ /--\ / /\ /----\ OR / /\ \ /------\ / /__\_\ /________\ /_/______\

Papyrus sheets came in all sizes, depending on the size of the usable strips cut from the plant; the largest known are as much as two-thirds of a metre (say 25 inches) wide, but the typical size was about half that, and occasionally one will find items not much bigger than a business card (presumably made of the leftovers of larger strips trimmed down to size). According to Pliny, these various sizes and qualities were given distinct names (Augustan, Livian, amphitheatre, etc.), but it is not clear that these distinctions were always observed. Various grades of papyrus were reportedly sold, although the details are somewhat obscure and should not detain us.

The best papyrus could be sliced thin enough that the final product was flexible and even translucent, like a heavy modern paper, though it could not be folded as easily. (To be sure, not all papyrus was this good, although I have not seen any information as to why; I have heard that Latin papyri have not lasted as well as Greek papyri, but I have no explanation for this, either. E. G. Turner reports that earlier papyrus was thinner and more paper-like, while late papyrus was thicker and more like cardboard. He blames this on poorer manufacturing, but I wonder -- given that we know papyrus went extinct, might the explanation not be that the best papyrus plants were used first, meaning that gradually only the coarser plants survived, with even those eventually going extinct?)

Papyrus is not paper, though. It is not as absorbent, and does not soak up ink as well. This means that papyrus should not be smoothed or polished; if it is, the ink will spread and puddle. The reason papyrus takes ink is that the surface is rough enough for the ink to have a lot of surface area to adhere to.

The plant itself Cyperus papyrus, shown at left, is a tall, slender stalk topped by a bushy growth of leaves. It grows in water, with the height of the stalk depending on the species and conditions but generally quite tall. The tallest papyrus sheet now known is 53.5 cm. tall (a little more than twenty inches), although 40 cm. (16 inches) is much more typical (that 53.5 cm. item was used for construction drawings).

It will tell you something about its importance that Herodotos seems to have called the plant itself by the "book-name" βυβλος or even βιβλος.

Those wishing to see Pliny's description of papyrus in full can find an English translation in C. K. Barrett's widely available The New Testament Background: Selected Documents; the description begins on page 23 of my 1966 edition. Much of the information is restated in Sir Edmund Maunde Thompson, An Introduction to Greek and Latin Paleography.

On occasion, papyrus would be treated with cedar oil to guard it from moths. This would also improve the smell -- there are reports of people burning papyrus as a sort of incense, and I suspect they were using the cedar-treated type -- but it had the side effect of turning the material yellow.

What happens after the sheets were made depends on the purpose for which the papyrus is intended. Individual sheets of papyrus were of course often sold for use in record-keeping, memoranda, writing training, etc. It is believed that some really coarse papyrus was used exclusively for wrapping rather than writing. But we are most interested in books. When working with papyrus, the scroll was genuinely the more convenient form. The individual leaves were bound together edge to edge. The standard roll, again according to Pliny, was twenty sheets, (glued together with a flour-based paste or perhaps sometimes sewn) and was called a scapus. This would mean a scroll about 5 metres long. Assuming the sheets were square, this would hold 4000-5000 words, or the equivalent of six to ten pages of a printed book. And this length really does seem to have been standard; many texts of the Ptolemaic period are written with a lot of empty space, implying that they were being puffed up to fill a standard scroll. But there was no reason why such a roll could not be lengthened or shortened; longer scrolls are certainly known -- Papyrus Harris I, British Museum 10053, is roughly 40 metres long). This apparently was just an informal standard. It is perhaps illustrative that Juvenal once made a wisecrack about a play so long that it had to be written on both the inside and outside of a standard scroll (and still didn't fit).

It was also easy to add to a scroll, since you just added a sheet at the end. For a codex, you had to add a whole quire. This might explain why scrolls were still used in the Middle Ages for some specialized purposes such as mortuary rolls, where the particular institution might keep adding more records of the dead.

What's more, a scroll might be cut in half, or even quarters, horizontally, giving a scroll only about 15 cm. or even 8 cm. high (six inches, or three inches). The latter strikes me as difficult to use, because the columns were so short, but it would allow scrolls of the standard length (and hence diameter when rolled up) which still allowed for shorter texts.

In general, according to Pliny, the best sheets were placed on the outer edge, both because they took more wear and tear and because they were the most certain to be written on; the last sheet or two, which were the worst, were the least likely to be used. (Of course, putting the best scheets on the outside also made the scroll look better and more saleable.) The first sheet was a πρωτοκολλον, a word which gave rise to our protocol, although the word εσχατοκολλιον for the last sheet seems to have left no descendents in modern languages.

It was common although not universal to use a few extra cross-strips of papyrus (sometimes re-used papyrus) to stiffen the outer edge of a scroll; such cross-strips are occasionally found at the inner end as well, but this is much less common.

When papyrus sheets were bound together to make a scroll, there was usually an overlap of a centimeter or so between the sheets to hold them together. Normally the sheets were pasted together in such a way that the left hand sheet was placed above the right hand sheet, so that, as one was writing, the right hand sheet was below the left hand -- in effect, one wrote "downhill."

Scrolls have the advantage that they allowed a continuous curve, which did not excessively stress any particular point of the papyrus (at least as long as there was a large empty region at the center; they were usually rolled up to form an open circle ⚪︎ rather than a filled circle ⚫︎). A papyrus codex had to have a single sharp fold (either in a single sheet or at the joining of two sheets). This naturally was a very fragile point; even the nearly-intact 𝔓66 is much broken at the spine, and to my knowledge, only one single-quire papyrus (𝔓5) has portions of both the front and back sheets of a folded leaf (and, in fact, I know of no proof that the two halves -- which are not joined; they are part of the middle of a page -- are in fact part of the same sheet, though it is generally assumed and several scholars have made rather extravagant assumptions on this basis). On the other hand, if a scroll got loose and unrolled itself in the wrong way, it could cause quite a mess, and get damaged by folding, in a way a codex could not.

Scrolls also allowed the reader to read continuously, showing as much of the document as one desired at any given time. This wasn't very helpful for ordinary reading, but it was a big advantage in reading music (as any musician who has to turn pages in the middle of a piece will tell you). Therefore scrolls continued to have a specialized use in the Middle Ages to hold musical works too long to be written on a single sheet or on facing pages.

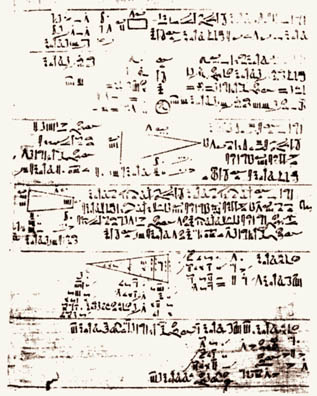

Scrolls were made to certain standards -- e.g. the horizontal strips of each sheet were placed on the same side of the scroll, since only one side was likely to be written upon, and it was easier to write parallel to the strips. See the illustration at right, of the Rhind Papyrus, clearly showing lines between papyrus strips. (The Rhind Papyrus, acquired in 1858 by A. Henry Rhind, is a fragmentary Egyptian document outlining certain mathematical operations. It was written by a scribe named Ahmose probably in the Hyksos period, making it, in very round numbers, 3700 years old; it is thought to be a copy of a document a few hundred years older still, written during the period of the Twelfth Dynasty. This makes it one of the oldest mathematical documents extant.)

It is widely stated that (with the exception of opisthographs) scrolls were only written on one side, and that this was always the side where the strips ran horizontally. As we saw, Pliny stated that poorer quality material was often used on the back of a sheet, since it would not be written on; sometimes papyrus leaves were used for this purpose instead of papyrus fibre, since the goal was not beauty but strength. While it seems to be nearly always true that Greek papyri are one-sided, Egyptian papyri sometimes used both sides, and we are told that some papyri had their texts written on the inside and a summary on the outside.

Most scrolls were set up so that the lines of writing paralleled the longer dimension of the scroll -- that is, if ≈≈≈ represents a line of text, a typical scroll would look something like this:

+---------------------------------------------+ | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | +---------------------------------------------+

Suetonius, however, says that pre-Imperial Roman legal scrolls went the other way, that is

+----------+ | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | | ≈≈≈ ≈≈≈ | +----------+

If there are survivals of this format, though, my sources fail to mention it. There are, among Egyptian papyri, a few (mostly from the Middle Kingdom) which mix the formats!

It is thought that early papyrus rolls were sewn together, but this caused enough damage to the pages that bookmakers early learned to glue the sheets together. From ancient descriptions and illustrations, it seems that the scroll would would then normally be wrapped around a rod, usually of wood (Hebrew Torah scrolls generally had two rods, at inner and outer ends), though few such rods survive. It was not unusual for a titulus, or title-slip, to be pasted to the outside. Indeed, it has been suggested that this explains the mystery of the Letter to the Hebrews, which when originally filed had a slip on the outside listing its author or destination, but that this was lost early in its history (something which reportedly often happened to such slips). I will admit to thinking this unlikely; surely someone would remember what the scroll was, if it was respected enough to eventually become scripture! Other scrolls placed a summary at the beginning of a roll, so that its contents could be easily learned without unrolling the whole thing.

In parchment codices, it was normal for hair side of a sheet to face hair side, and flesh side to face flesh. There was no similar rule for papyrus. Some codices were set up so that the pages with horizontal strips faced those with horizontal strips and vertical face vertical (𝔓66 is an example of this), but others are set up so that the pages have horizontal facing vertical (𝔓75 is of this type).

One of the real problems with papyrus was its fragility. Damp destroys it (there are a few reports of papyrus palimpsests, but they are very rare -- how do you erase a manuscript without wetting it?), which is why papyrus manuscripts survive only in Egypt and a few other very dry locations. And while exposure to dry weather is not as quickly destructive, the papyrus does turn brittle in dry conditions. It would be almost impossible make, say, a volume that would be used for regular reference on papyrus; it just wouldn't last.

(Which makes it somewhat ironic that damp is often used to unroll a scroll which had stiffened in a rolled-up state. The typical approach was to place the scroll in an enclosed space with damp blotting paper and perhaps a chemical to prevent mold from forming. It would be left in this state overnight, then unrolled. If the roll was large, this might have to be repeated. Ideally it will then be placed between glass sheets to preserve it in its unrolled state. Other techniques for unrolling include static electricity and heat, although this is better for making the sheets cease to adhere to each other than for actually unrolling them.)

Papyrus can also attract mold, and it was not unknown for rodents to chew on it. Also, it seems to have attracted insects, particularly white ants. In other words, there were lots and lots of ways for a papyrus document to be destroyed.

On the other hand, if treated carefully, papyrus could last quite well. Galen is said to have studied a papyrus that was 300 years old, and Turner reports a papyrus with writings from two different eras, one three centuries after the other. There are papyri from Egypt that are more than 3000 years old, and although few ancient papyri are known from Europe, there is one (burned) papyrus from Greece believed to date from the fifth century B.C.E.

It will be seen that papyrus was used as a writing material for at least three thousand years. It is nearly sure that the earliest Christian writings were on papyrus. As the church grew stronger and richer, the tendency was to write on the more durable parchment. Our last surviving papyrus Bible manuscripts are from about the eighth century. It is thought that manufacture of papyrus ceased around the tenth century.

This may not have been voluntary. Papyrus plants are now rare in Egypt -- E. Maunde Thompson, An Introduction to Greek and Latin Paleography, p. 21, declares them extinct in that country, although still found further up the Nile. It is reasonable to assume that the heavy demand for writing material caused the supply of the plant to dwindle. Presumably, given time, the population would eventually be restored -- but with the banks of the Nile now having been so heavily developed, and the river itself regulated, the environment is no longer what it was thousands off years ago. A form of papyrus has been reintroduced to Egypt in 1872, according to Richard Parkinson and Stephen Quirke, Papyrus, p. 9 (who say that the original form was extinct by the time Napoleon's expedition went looking for it), but the reintroduced form came from a French botanical garden and may not be the same species as the original. Parkinson and Quirke, p. 8, show a map of where papyrus still flourishes; the northernmost point appears to be right around the Egypt/Sudan border.

Leo Deuel, in Testaments of Time: The Search for Lost Manuscripts & Records (p. 87), reports "[the] Church continued using papyrus for its records and bulls into the eleventh century. The last document of this nature which bears a date is from the chancery of Pope Victor II, in 1057." (The last dated medieval papyrus document of any kind is apparently an Arabic writing of 1087.) Ironically, after that, the material became so obscure that people in Europe forgot what it was -- hence the fact that "paper" has such a similar name; the two were confused, with paper (which had no native name in Western languages) being called by a name derived from "papyrus." It was not until Napoleon's Egyptian expedition that Europe really rediscovered papyrus, and not until 1877 that a large discovery in the Fayyum really made it clear that there were vast riches to be discovered.

There is some uncertainty about how expensive papyrus was. Jac Janssen reports a source that gave the price of a roll -- presumably a standard roll of twenty sheets -- as two deben, which was the price of a large basket or a small goat. Another source gives the price of a roll as one to two days' wages for a laborer -- not horrendously expensive, but not something you just went out and bought on a whim, either. My very rough estimate is that a complete New Testament would have taken twenty such scrolls, so to acquire a New Testament would have required five weeks' wages for a labourer, or a small flock of goats. Which in turn would mean that a church of a few dozen members could probably afford the cost of papyrus for a complete New Testament, but the copying would be another matter....

In ancient Egyptian, papyrus was referred to either as meḥyt or tjufy; the latter, the ancestor of Coptic djoouf, referrs specifically to papyrus while the former perhaps describes a wider class of reeds or water plants. In Greek, παπυρος refers to papyrus as a food plant, while βυβλος tended to refer to the plant when it was used in making a writing material or other manufactured item such as a basket. The resulting writing material itself was χαρτης, which obviously gave us Latin charta and English charter.

The Jews of course continue to use scrolls to this day, although not on papyrus. Jewish scrolls have two interesting peculiarities: Because Hebrew is written from right to left, the scrolls are rolled in the opposite direction from Greek or Latin scrolls, and they also tend to use wider columns than pagan scrolls (sometimes as wide as 20 cm/8 inches).

Although the scroll was the usual format for "books" in ancient times, "letters" were another matter, at least in Egypt. A letter could be expected to be folded up rather than rolled. Given that much of the New Testament consists of "letters," his perhaps has implications both for textual criticism (damage to the text would be most likely along the folds) and literary criticism (letters would break at the folds, and perhaps be reunited out of order or in unrelated blocks, which would help explain letters like 2 Corinthians with its abrupt changes in tone and topic).

Jeremiah tells us that deeds of sale were sealed, and we know that some Egyptian scrolls were also sealed after being rolled up. But they were usually sealed with mud rather than wax, so it is likely that many scrolls which once had such seals have lost them.

(It should incidentally be noted that, although the fibre of papyrus was used as a guide to writing, allowing scribes to maintain a straight line without ruling the papyrus, the fibres often did not run the entire length of a sheet. This can be a problem when reconstructing a sheet from fragments. If you see what appears to be a similar pattern of fibres on two sections, you cannot assume they align unless the two fragments actually fit together.)

Although most "papyri" are made of papyrus, it is reported that a few German writings were made on willow fibre, which could look like papyrus. I know of no Biblical manuscripts of this type.

Incidentally, in this era of manuscript fakes, it is reported that, in ancient times, it was possible to make papyri look older and so more significant: Papyrus writing materials, originally white, were sometimes exposed to wheat to make them look older, yellower, and more worn.

Also, although we often say that papyrus and skin (parchment, vellum) were separate writing materials, it is not rare to see both in the same volume. True, mixed quires were rare (since papyrus was so much more fragile) -- but, for that very reason, papyrus codices were often bound in leather or parchment covers. The Nag Hammadi codices are a good example of this.

Parchment

The history of parchment is among the most complicated of any writing material. The historical explanation, both for the material and for the the name, comes from Pliny (Natural History xiii.11), who quotes Varro to the effect that a King of Egypt (probably Ptolemy V) embargoed exports of papyrus to Pergamum (probably during the reign of Eumenes II). This was to prevent the library of Pergamum from becoming a rival to the Alexandrian library. Eumenes's people then developed parchment as a writing material, and the term "parchment" is derived from the name Pergamum.

The difficulty with this hypothesis is that skins were in use for books long before the nation of Pergamum even existed -- although even as late as the time of Jerome, papyrus was considered a better material for letters (my guess would be that this was because papyrus had a more porous surface, meaning that the ink would soak in and dry quickly, whereas ink on vellum would need an extended drying period. Ink on particularly smooth parchment was in fact likely to flake off, leaving no mark behind; this was reportedly a particular problem with Italian parchment, which was polished very heavily.)

Parchment must really be considered the result of a long, gradual process. Leather has been used as a writing material for at least four thousand years; we have from Egypt the fragments of a leather roll thought to date to the sixth dynasty (c. 2300 B.C.E.), with an apparent reference to leather as a writing material from several centuries earlier -- all the way back to the early fourth dynasty. Given that the handful of clay scribbles from the pre-dynastic period do not seem to involve an actual writing system, this would seem to imply that the use of skins dates back almost to the standardization of the Egyptian writing system. We have a substantial leather roll from the time of Rameses II, and one which cannot be precisely dated but which is thought to go back to the Hyskos era several centuries before that. And, of course, there is the long tradition of writing Jewish scripture on leather. The Dead Sea Scrolls, for instance, are written primarily on leather.

But leather is not truly parchment. Leather is prepared by tanning, and is not a very good writing material; it is not very flexible, it doesn't take ink very well, and it will usually have hair and roots still attached. It's good for book bindings, but that is not the same thing.

|

Parchment is a very different material, requiring much more elaborate preparation to make it smoother and more supple (the technical term is "tawing"). Ideally one started with the skin of young (even unborn) animals (typically sheep, cattle, or goats, but other materials have been used -- in Iceland, there are even instances of sealskin used for books, and Tischendorf thought ℵ was written on antelope skin). This skin was first washed and cleansed of as much hair as possible. It was then soaked in lime, stretched on a frame, and scraped again. (The scraping was a vital step: If any flesh at all remained on the skin, it would rot and cause the skin to stink terribly. Scraping was done with a special knife, the Lunellarium.) It was then wetted, coated in chalk, "pounced", that is, rubbed with pumice (or, in England and other places where pumice was unavailable, in a bread with ground glass baked in to produce a pumice-like texture), and finally allowed to dry while still in its frame. This process obviously required much more effort, and special materials, than making leather, but the result is a writing material some still regard as the most attractive known to us. Certainly parchment was the best writing material known to the ancients. Smoother than leather or papyrus, it easily took writing on both sides, and the smoothness made all letterforms easy -- no worries about fighting the grain of the papyrus, e.g. And it was durable. Plus it was quite light in colour, making for good contrast between ink and background. And, because the surface was smooth, it could be painted. I have never seen an instance of a true oil-color illustration on papyrus (there may be a few, but I don't know of it), but many vellum manuscripts are decorated with miniatures. These rarely add to our knowledge of the text, of course, but many are quite beautiful. |

An illustration from a Latin codex (Copenhagen, Kongelige Bibliotek, MS. 4, 2o, folio 183v) shows a parchment-seller. In the background is the rack on which a parchment is being stretched, as well as a scraper. |

This does not mean that parchment was a perfect writing material. It is denser than papyrus, making a volume heavier than its papyrus equivalent. And the pages tend to curl -- particularly a problem when it is touched by a human hand; the heat of the hand, and the perspiration, cause it to curl even more. Parchment books often had clasp bindings specifically to keep the parchment from curling. Plus it was always expensive. It is noteworthy that not one parchment manuscript was found in the Herculaneum or Pompeii excavations; every one of the surviving scrolls was of papyrus. As long as papyrus was cheap, parchment was a special-purpose material.

And, just as with papyrus, there are differences between the sides: The flesh side is darker than the hair side, but it takes ink somewhat better. The differences in tone caused scribes to arrange their quires so that the hair side of one sheet faced the hair side of the next, and the flesh side faced the flesh side. It is reported that Greek manuscripts preferred to have the flesh side be the outer page of a quire, while Latin scribes tended to arrange their quires with the hair side out.

(There are exceptions to the above rules; in the island of Britain, "insular" parchment seems to have been prepared differently; it was stiffer and had less difference between flesh and hair sides. This reduced the need to place an even number of leaves in a quire, because there was no requirement that hair face hair and flesh face flesh.)

Another disadvantage of parchment, from our standpoint, is that it was reusable. Or maybe it's an advantage. The very smoothness and sturdiness which make parchment such a fine writing material also make it possible to erase new ink, and even old writing. Combine this with the expense of new parchment and you have ample reason for the creation of palimpsests -- rewritten documents. Many are the fine volumes which have been defaced in this way, with the under-writing barely legible if legible at all. And yet, had they not been overwritten, the books might not have survived at all; who can tell?

To be sure, from the writer's standpoint, the ability to erase was an advantage. Because erasures could be partial. A scribe working on papyrus wrote, and having written, moved on. Corrections were simply crossed out. But scribes working on parchment added a sponge and a scraper to their tools. Fresh ink could be blotted up with the sponge. Ink that had dried could still be scraped off. This meant that parchment manuscripts were often more attractive to the reader. One suspects it also encouraged illustrations, since one errant stroke did not have to ruin the whole drawing.

The final problem with parchment was cost -- which was high for many reasons. Animal products inherently cost more than plant products, plus (as we saw) parchment required a lot of preparation. And the supply was limited. On the other hand, the price was not absolutely prohibitive; the cost of copying was generally greater than the cost of the parchment. Cambridge, Peterhouse College MS. 110, for instance, includes a price inventory for its preparation: 3 pence per quire for parchment, 16 per quire for copying, eight for illumination, and two shillings for the binding. Illumination and binding were of course separate from the cost of copying, but it would seem that, by this time (late middle ages) scribal work cost about five times the price of parchment. So if someone could afford a book at all, the parchment was not the limiting factor.

Barring DNA testing or the like, it is rarely possible, just by looking at it, to tell what sort of skin was used to make parchment. There are exceptions, which ironically typically involve cheaper parchment that hasn't been as well prepared. In such parchment, it may still be possible to see the hair follicles. Different animals had different follicle densities, so it may be possible to determine the animal based on the spacing of the follicles.

One of the most interesting contemporary accounts of the preparation of parchment comes from the Old English codex known as the Exeter Book. This contains a series of riddles. Several pertain to the act of bookmaking. #26 is perhaps the most interesting. I won't give you the Old English version (which is incomprehensible to most moderns), but the following is based on a comparison of three modern English translations.

An enemy robbed me of life, stole my strength, then washed me in water and drew me out again. He set me in the sun, where soon all my hair came off. Then the knife came across me, cutting away all my blemishes. Fingers folded me, and a bird's delight spread black droppings over me, back and forth, stopping to swallow droppings from a tree, then marking me more.

Then a man bound me with boards, and stretched skin around me, and covered it with gold. A smith wound his wondrous work around me.

Now let this art, this crimson dye, and all this fine work celebrate the Ruler of nations everywhere, and proclaim against folly. If children of men will use me, they will be safer and surer of salvation, their hearts bolder and their minds wiser and more knowing. Friends and dear ones will be truer, more virtuous, more wise, more faithful. Fortune and honor and grace will come to them; kindness and mercy will surround them; they will be held tight in love.

What am I, this thing so useful to men? My name is renowned. I am bountiful to men, and holy.

The answer considered to be a gospel book. Animals are killed, and their skins made into parchment; they are written upon with a pen of a bird's quill (and, in some instances, a coating derived from eggs), with ink made from tree gum, then are bound, and the binding decorated; the book then goes to serve in a church or monastery.

We might add incidentally that "parchment" is not the native English name for the material; it derives from French. In Old English, the name was bók-fel, book-skin. The French name, of course, came into use after the Norman Conquest.

Although any skin could be used for papyrus, some skins were clearly better than others. It is said that "Fat sheep made good mutton but bad parchment," and of course the largest books required the skin of a full-sized cow -- which in turn tended to mean stiffer skin! And even if the skin was good, it really needed to be supplied to the parchment-maker promptly, before the flesh started to decay.

As mentioned above, without detailed (and sometimes destructive) tests, it is sometimes hard for investigators to tell what animal's skin was used to make parchment, but there are differences. For example, it is relatively easy to erase ink from calfskin, but very difficult to remove it from sheepskin.

Parchment also has an interesting characteristic not shared with paper or papyrus. Both paper and papyrus scorch if heated mildly, and burn if heated heavily enough or exposed to fire. Parchment is much less flammable, and even if exposed to high heat, its behavior may be different. Parchment, no matter how carefully prepared, will usually contain at least some fat -- and fat denatures in heat. It might melt and coat the manuscript. It might melt, run out, and burn, scorching only part of the parchment surface. It might melt in some places and not others, or the collagen fibers which give the parchment its strength might collapse, causing the manuscript to differentially contract. So a parchment exposed to fire may wrinkle badly. This can also cause the parchment to become brittle. It may also seal the volume shut. All of these effects can be seen in the burned volumes of the Cotton Library in the British Museum. To this day, there isn't much that can be done to restore such books -- the standard technique is to humidify the parchment as much as possible (using humid air, not water!), then press the skin to try to flatten it out, and hope the ink and illuminations don't flake off.

Paper

There is little that needs to be said about paper -- odds are that you know what it is! -- except that early paper was made from rags, e.g. of linen, or sometimes cotton or hemp, rather than wood pulp, and that, in the west, it became popular as a writing material only around the twelfth century.

Rag paper apparently was invented in China around the beginning of the second century C.E.; Douglas C. McMurtrie, The Book: The Story of Printing & Bookmaking, third revised edition, Oxford, 1943, p. 61 reports that an official named Ts'ai Lun was given official recognition for the invention in 105 C.E. This early paper typically had a yellowish color.

Paper gradually spread westward, and was in widespread use in the Islamic world by about the ninth century. McMurtrie, p. 65, reports that "The oldest extant European paper document is a deed of Count Roger, of Sicily, written in Latin and Arabic and dated 1109."

The first European paper mill reportedly was opened around 1270 in Italy. The spread was slow; England didn't get its first mill for another two centuries. (And even that was a temporary foundation; although England never ceased to print cheap books, for the next several centuries, English books were printed on higher-quality continental papers.) It is likely that many paper Biblical manuscripts were written on paper from Islamic countries. Acceptance of paper in the west did not come easily -- in the year 1221, the Emperor Frederick II explicitly declared that documents on paper were not legally binding (McMurtrie, p. 67). Fortunately, the Greek East was not so short-sighted, or we would probably have rather fewer New Testament manuscripts. It was not until the mid-fourteenth century that paper was generally accepted in the west. For a time, there were instances of books with mixed parchment and paper -- typically with parchment supplying the outermost leaf of a quire, and perhaps the inner leaf also. This was perhaps to take advantage of the greater durability of parchment.

Although it took less time to prepare paper than parchment, it initially wasn't fast -- there were many steps, and each sheet required some individual handling. (Little wonder that early paper had large sheet sizes, since a large sheet had much more paper but required only a little more work.) The rags from which it was made had to "rot" for four or five days, then were washed clean, pulverized, mixed into a slurry. This pre-paper material was pressed in a frame, laid out on felt, dried, pressed again, sized, and usually pressed some more (see Mark Bland, A Guide to Early Printed Books and Manuscripts, pp. 32-34).

Because the paper was made in metal wire frames, the pattern of wires from the very beginning made it possible to determine whether paper came from the same frame. Starting around 1270 (McMurtrie, pp. 71-72), it became the habit to put a second layer of wire above the bottom of the frame, leaving a signature mark -- a watermark -- on the paper. These can be used as an indication of date -- especially since the frames had to be periodically rebuilt, so the watermark would change very subtly every few years. Curiously, little seems to have been done by New Testament paleographers to take advantage of the information this offers (which can often be used to date a paper stock to within two or three years) -- some manuscript descriptions describe watermarks, but not in enough detail to be useful. Perhaps this is because the watermarks themselves (as opposed to the marks of the wire frames) were so widely used -- some of these watermarks became so standard that they came to refer to a particular type of paper rather than the individual mill which produced it -- e.g. "crown folio" became a particular paper format (Bland, p. 27). But I suspect that it is mostly because manuscripts on watermarked paper are minuscules, mostly late, and not taken very seriously.

After being removed from the frame, paper was typically placed on felt, pressed, and dried, after which it was sized -- that is, coated with size, a gelatin material that smoothed the surface. This made it possible to write on the paper without blotting. (Erick Kelemen, Textual Editing and Criticism, p. 35, compares writing on un-sized paper with trying to write with a fountain or roller pen on a paper napkin. The use of size can be important in detecting forgery, because if a modern forger uses old paper to try to avoid being caught by radiocarbon dating, the size may well have come off the paper, causing the ink to spread out more. Blotty, runny ink can thus be an indication of a forgery, although it's not proof because there were of course papers that weren't very well sized in the first place. ) For more about size, see the article on Chemistry.

Because paper had to be made in a frame that was manipulated by hand, sheets had a maximum size of about 0.7x0.5 meters (about 28 inches by 20 inches) -- smaller than the largest parchment sheets! (Bland, p. 32). The typical "pot" paper of the late Middle Ages was about .4x.3 meters, or about 16 inches by 12 inches.

Some additional detail can be found in the section on Books and Bookmaking.

Clay (and other rock-like materials)

It may seem odd to include clay as a writing material, since there are no clay New Testament manuscripts. But there are ostraca and talismans, some of which are clay, and of course there are many pre-New Testament writings found on clay: The cuneiform texts of Babylonia and Sumeria, plus the ancient Greek documents in Linear B. Since these give us our earliest linguistic evidence for both Greek and the Semitic languages, it is hardly fair to ignore these documents.

Such of them as are left. It is not just papyrus that is destroyed by water. Properly baked clay is fairly permanent, but sun-dried clay is not. Which is probably why our earliest ostraca are believed to be from the Egyptian Old Kingdom. It would be another thousand years before they appear in Greece, and even there, survival is spotty. Most of the Linear B tablets that survive from Pylos, for instance, survived because they were caught in the fire that destroyed the citadel. A number of cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia, initially perfectly legible, are now decaying because they were displayed in museums which did not maintain the proper humidity (in some cases, indeed, the curators left them encrusted with salts, which hastens the process of destruction). We think of clay as if it were a rock, and we think of rocks as permanent -- but it really isn't so. Who can say what treasures on clay have been destroyed, possibly even by moderns who did not recognize what they were....

Fortunately for us, it is unlikely that many copies of the New Testament were written on clay.

The other major disadvantage of documents on clay was their weight. My very, very rough estimate is that a complete New Testament would require about 650 tablets and would be too heavy for an ordinary person to carry. Plus you'd need a way to keep the tablets in order.

In addition to ostraca, there are a few ancient writings on limestone, mostly from Deir el-Medina in Egypt. Presumably limestone was adopted as a writing material because it was cheap, but some of these writings are on surfaces that were clearly carefully smoothed for writing. So maybe limestone became a tradition. And a limestone block would be harder to break than a pot. But probably even heavier....

Wax

As far as I know, there are no New Testament writings preserved on wax. Indeed, as far as I know, there are no ancient writings of any sort actually preserved on wax (we have a number of the tablets which held the wax, but the wax itself, and the writing on it, is gone). We should however keep in mind the existence of wax tables, because there are indications that they were often used to prototype portions of actual manuscripts -- especially illustrations in illuminated manuscripts, but I wouldn't be surprised if they were used for commentary texts as well, because these sometimes required elaborate layouts.

A typical wax tablet was used for jotting quick notes. Apparently the standard was a wooden tablet, lined with beeswax, written with a stylus (metal or bone), and tied with a leather thong so it could be carried around the next.

Wax tablets did have a "security advantage" over something written on another medium: A message could be written in a multi-leaf tablet, and the two leaves bound together by cords, over which a seal was applied. This could be used in several ways: To maintain the secrecy of the inner message, or in some cases to assure that the inner message matched the outer.

Reportedly, the standard for waxed tablets was a black wax (so Maunde Thompson's An Introduction to Greek and Latin Paleography, p. 15), even though it would seem that this would make it harder to tell the writing from the background. Quintillian in fact recommended the use of parchment (which was erasable) for those with weak eyes who could not easily read scribbles on wax.

Styli eventually were created with a sharp end for writing and a broad, flat end for rubbing out any old messages in the wax. Thompson reports that some in fact had three blades: The point, for writing, the flat, for smoothing -- and a third projection, at right angles to the shaft, for drawing lines on the wax. (Although what good lines on wax would do is beyond me. Practice, maybe.)

Other Materials

Many other writing materials have been used at one time or another. In the east, silk was sometimes employed. Linen was used in Egypt, and probably by the Romans as well, although it appears that linen was never woven for the purpose of being a writing material; the cloth in all surviving linen documents had originally been created for a different use. Potsherds were often used for short scribbles -- they were standard for Greek elections, for instance. (Hence the English word "ostracism," because the Greeks voted on who to ostracize, and the votes were recorded on ostraca.) Leaves and bark have sometimes been employed as writing materials -- early palm leaf books have survived in significant numbers. But few trees in the Christian world grew suitable leaves; there seem to be no Christian documents of this type.

Wood was used in a variety of ways. We have a few examples of notes written on wood in ink, or scratched into wood; this may have been relatively common in some areas, but since wooden writings were not kept in libraries, and would gradually decay in damp, very little of this sort of thing survives, and none of it of Christian significance. In Egypt, wood tablets (usually of sycamore) were coated with plaster and written on; this allowed correction or erasure by rubbing or, if that failed, by putting on another layer of plaster. But, as with papyrus, wooden writings rarely survived except in the dry climate of Egypt.

For permanent records, metal was sometimes used, either cast (i.e. molten metal was poured into a mold of some sort) or engraved. Romans had laws written in lead, and even some lead writing tablets, and bronze was sometimes used for very permanent records such as treaties. Bronze was also used by the Romans for the awards given to soldiers who had earned citizenship. It is possible that Paul carried such documentation, although obviously there is no BIblical evidence of this.

I know of only one piece of actual Judeo-Christian writing on metal, however: The famous Copper Scroll from Qumran (and even that did not contain a Biblical text). Although metal might seem like an ideal material for books, it in fact had several disadvantages. For starters, it's hard to write on. Inks normally soak into the surface on which they are written, but not on copper! A copper book, unless engraved (a slow process), would have to use a non-runny ink, and would have to be allowed much time to dry. A metal scroll has an additional disadvantage: The metal will not roll well. Copper is a soft metal, and malleable, so it is possible to make a scroll from it (a scroll of, say, iron, would be almost impossible). But the copper can be bent, or otherwise damaged, and will not take well to repeated rollings and unrollings. And, over time, it oxidizes; the Qumran scroll, when found, could not be unrolled, and had to be sliced apart to be read. (A procedure developed for dealing with burnt papyrus scrolls such as those from Herculaneum.)

Reeds, Quills, and other Writing Instruments

The tools for writing date back so far that the Egyptian heiroglyph for writing seems to have been based on a pen-case tied to an ink palette (one highly detailed carving of the symbol shows the palette as having two wells for, presumably, two different colors of ink).

The first pens we know about were made of rushes (supposedly the Juncus maritimus). They were thick and very difficult to use; rather than having a split tip to hold a significant amount of ink, the tip was placed in water and then rubbed against a pigment, and a few letters would be written before it went dry and the process had to be repeated. And they could only make strokes in certain directions -- a right hander holding a rush pen in a normal way could not make a stroke from lower right to upper left, and all strokes from right to left were difficult. It took practice to write with them.

And Egyptians, based on illustrations, did not use a desk at this time; they just sat with the papyrus in their laps and wrote on it. It must have been a very hard way to write, although rush pens did have minor advantages: they didn't have to be repeatedly re-cut, and they wrote better on non-flat surfaces. And you didn't have to press as hard on the writing material, meaning that the papyrus could be thinner.

Small advantages indeed. It must have been a relief to get rid of those things. It appears that the earliest really practical writing utensils were made of reed (although even these may have used un-split reeds at first). In 3 John 13, we read of the author writing with a καλαμος, which is certainly a reed of some kind. If any New Testament manuscript was written with a rush pen, I have not heard of it.

It is said that the standard plant used to make reed pens was the Phratmites aegyptiaca.

At some stage, reeds started to give way to quills -- feathers of large birds. (The very word pen is from Latin penna, feather; compare English "pinion.") This usage is old enough that Old English called its writing implements "feðer," fether. However, it was not a sudden and complete shift from reeds to feathers. Quills seem to have provided a smoother flow and probably sputtered less, but reeds could have their own advantages -- it was easier to adjust the tip size, and one could also in some instances create a better hand hold. It has been claimed that quills were not suitable for writing on papyrus -- their stiff points would skip and/or scratch. Also, although feathers are common, those suitable for quills aren't, really -- supposedly the only high-quality quills came from geese, swans, and ravens, and the best feathers were the third or fourth of the wing, plus the pinion. To print very large letters, a vulture quill was used; crow quills were used for very small print. A feather from a smaller bird was probably fairly useless. It also took a fair bit of skill and dexterity to cut a quill -- and, indeed, quills had to be cut different ways for different styles of script; it was cut at an angle to write a Gothic hand, while italic hands and others used a rounded tip. Reeds were thus cheaper and perhaps more forgiving.

There is strong evidence that reeds and quills were used simultaneously in Anglo-Saxon England -- one of the riddles in the Exeter Book describes writing a book with a quill, while another describes a reed. The following poetic translation is based on one by R. K. Gordon (I've improved the meter -- at least to my ears -- at slight cost to the accuracy of the rendering):

Beside the shore and near the strand,

Where the sea beats on the land,

I dwelt there, rooted in my place,

And few there were of human race

Who saw my lonely home abode,

Where ev'ry morn the brown wave flowed,

And in its wat'ry clasp me caught,

And little had I any thought

That it should ever be decreed

That by the bench where men drank mead,

I, mouthless once, should speak and sing

Both soon and late. A wondrous thing

To mind which cannot understand

How point of knife and firm right hand

A man's mind coupled with the blade

Cut and pressed me, and so made

Me give a message without fear

To you with no one else to hear,

So that no other man e'er may

Tell far and wide the words we say.

Few modern references even mention pens in this period, but they did exist, made of bronze or bone. It is likely that pens were used primarily for parchment, which had a smooth surface; a hard nib might have damaged papyrus. The suggested rule of thumb is that papyri were written with reeds, parchments with quills or, sometimes, manufactured pens.

A few other writing implements came into existence over the years. Pencils probably need little explanation. But you may also find references to "crayons." This is a doubly deceptive description -- the term "crayon" had not been coined in the manuscript era, and modern wax crayons didn't exist either. But wax might sometimes be used to bind a color, or some sticky material combined with a pigment to create a waxy inscription similar to that of a modern crayon.

Ink

The ideal ink (the name itself being a French word, from enque; the Old English word was blaec) has three characteristics: Permanence, clarity of color, and strong attachment to the page. These three attributes were rarely found together in ancient times.

For a strong black, the ideal substance was lampblack, which is almost pure carbon. By itself, unfortunately, it did not adhere to the page very well, resulting in writing that could flake off. Some scribes nonetheless used a lampblack ink, similar to modern "india ink," which is carbon mixed with a gum or glue.

The other basis for ink was galls -- nutgalls or oak gall, for instance. These are sometimes called metallic inks -- a description that would drive a modern printer crazy. (Metallic inks today look like metals!) Frequently the gall was combined with a "vitriol" -- in modern terms, a metal sulfate. Vitriols were often made with sulphuric acid -- hence a high acidity. The standard formula in England in the late middle ages was five parts gall, three of iron sulfate (FeSO4•xH2O), and two of gum. In Spain, the proportion was three parts gall to two parts iron sulfate to one part gum, and wine was used as the base liquid for writing on parchment, although water was used for ink used on paper. Some vinegar might also be added to improve the flow.

Gall-based ink usually was brown rather than black (modern inks based on metal sulfates and tannic and gallic acid are very dark black, and permanent, supposedly getting darker as they age, but I gather the formulation has changed). Apart from this, it had advantages and disadvantages. It was more acidic than lampblack-based inks -- which meant that it adhered to the parchment better (since the acid etched the surface slightly), but if the acidity was too great, it could damage the surface. (True metallic inks, such as the gold used on some purple manuscripts, were even more acidic and caused worse damage.)

Lampblack-based inks, assuming the ink stayed on the page, are far more color-fast; inks written with this sort of ink (including the Qumran scrolls) usually still look black to this day. Gall-based inks tend to fade -- Codex Vaticanus, for instance, was written with a gall-based ink, and faded enough that it was famously retraced. Codex Bezae is another well-known manuscript written with gall ink.

It is reported that the ink of squid (cuttlefish) was also used on occasion. I know of no manuscripts which have been verified as using squid ink as a source of black, and do not know what the characteristics of such ink are.

Ink was often kept in an inkhorn, which in turn required a special hole in a desk to hold it.

For more on inks and pigments, see the article on Chemistry.

Other Tools Used by Scribes

Obviously pen and ink and writing material were the bare minimum equipment for a scribe. But most used many more implements. An illustration in the Latin Codex Amiatinus shows a picture of Ezra with (among other tools) a pair of dividers or calipers, a stylus for scoring lines, and an unknown triangular tool perhaps used for some sort of illustrations. Other scribes' kits included knives or scrapers for removing ink, as well as a knife (which might or might not be the same sort at the scraping knife) for putting new tips on their reeds or quills. Since these knives needed to be sharp, scribes often had whetstones to sharpen them. Those working on an illuminated manuscript would want a wax tablet to practice their illustrations. Most would need a straight edge for scoring lines. Sponges might be used to erase errors in newly-written text. The scribe might also have a pumice block for smoothing parchment, although ideally this would have been done by those responsible for preparing the parchment. Those doing geometric drawing would need a compass (which might also be used in ruling the manuscript). Some authorities believe scribes also used scissors, although I know of no absolute proof of this.

Technical Terms Used in Describing Writing

The list below shows some of the technical terms used in describing the act of writing.

- Ascender: the stokes of a letter that rise above the medial line (see under linear letters).

- Biting: when writing two letters, typically either with curves (e.g. oo) or with facing vertical strokes (e.g. bd, especially if written in a gothic font, 𝔟𝔡), overlapping the facing vertical or curved stroke to form one letter, e.g. ∞ for oo. Although biting has no significance for meaning, the manner in which it is done, and the frequency, and which letters are bittenn can often be an important clue in identifying scribes.

- Club, clubbing: large serifs used in many blackletter-type fonts, e.g. 𝔑 (N) has a club at the lower left corner.

- Curlicue: a flourish with enough curvature to curl back on itself.

- Cusp: a point at which two curved strokes meet, e.g. the leftmost point of the arrow at the end of this sentence is a cusp: ≺.

- Descender: the stokes of a letter that end below the baseline line (see under linear letters).

- Digraph: see ligature

- Finial: a curved stroke that terminates a letter -- e.g. ϗ as an abbreviation for και is a kappa with a finial; ϱ is a rho with a finial.

- Flourish: an ornamental stroke with no textual meaning (although it might have other purposes, e.g. for emphasis or to mark the end of a line). For example, ⱸ is an e with a flourish. Note that a stroke that looks like a flourish may have meaning -- it has been argued, e.g, that Middle English letters with flourishes should be read as being followed by an implicit e (so "sonɠ" should be read not as "song" but as "songe").

- Graph: essentially, a complete letter. So, for instance, the Greek graph Ξ consists of three rightward strokes one above the other; the English graph ƒ consists of a mostly-vertical stroke ∫ and a cross-stroke -. Note that "graph" does not mean the same thing as "letter"; "letter" is in effect an abstract concept, a way of recording a phoneme; a graph is the actual mark on paper. Thus Σ and Ϲ are different graphs of the same Greek letter, (upper-case) sigma; E and Ɛ are different graphs of the same Roman letter, (upper-case) E; s and ſ are different graphs of the same Roman letter, (lower-case) s, with the ſ being archaic and s being more modern.

- Ligature: the joining of two (or more) letters together, e.g. œ or ff or ffi (æ is not technically a ligature, since, in Anglo-Saxon at least, it's a single letter, aesc/ash). When both letters are vowels, and when joined form a single vowel, as with æ, the specific term digraph is used (because the two aren't just two letters joined together but two letters sounded together)

- Linear and non-linear letters. In most medieval and some more ancient writings, the standard was to write as if using a set of four ruled lines:

---------- top line

---------- medial line

---------- baseline

---------- underline

The baseline was the one used as the reference line; letters were written above it although some extended below it. In normal upper-case letters, every graph in the modern Roman alphabet extends from baseline to top line (i.e. are supralinear letters), and the same is true of most modern Greek letters, but not so in the lower case/minuscule letters.- double-length letters are letters that extend the full possible height, from top line to underline. In modern Roman alphabets, there are no double-length letters, but italic f is often a double-height (ƒ), and so were many medieval versions of the letter. Depending on script, Greek β ζ ξ φ ψ might be double-height letters.

- infralinear letters are letters such as g p q y that extend below the baseline to the underline, and above the baseline reach only the medial line. In typical modern Greek, infralinear letters are γ (η) (μ) ρ (φ) χ (ψ).

- linear letters are letters such as a c e m n o r u w x z that extend only from baseline to medial line. In typical modern Greek, linear letters are α ε (η) ι κ (μ) ν ο π σ τ υ ω.

- supralinear letters are letters such as b d h k l that extend from the baseline above the medial line to the top line. (β) δ (ζ) θ λ (ξ).

- minim: a very small (vertical) stroke, like an iota: ι. In medieval writing in the Latin alphabet, in particular, minims could be strongly emphasized and other strokes de-emphasized, so that the word "minim" itself could look like ιιιιιιιιιι, or ιιιiιιiιιι. Roman letters that, in medieval scripts, consisted primarily of minims were i m n u. For more, see the entry on minims

- Pen lift: the act of raising the pen from the writing surface between strokes.

- Single movement: a stroke which proceeds in a single direction without a pause or change in motion. So / would be a single movement stroke, but >, although a single stroke, is not a single movement.

- Stem: the primary upward stroke of a letter. Many letters are built around a single vertical stroke, although some, such as o, do not have a stem.

- Stroke: any mark made by a pen on the writing surface, as long as the pen is not lifted. There are various types of strokes:

- Broken stroke: a stroke which sharply changes direction, although without lifting pen from paper, as opposed to a single movement stroke. So v is a broken stroke, as compared to |, which is a single movement stroke.

- clockwise stroke: A circular or ovoid stroke drawn in the clockwise direction. So if the scribe draws a letter o like this, ⟳, it is a clockwise stroke.

- counter-clockwise stroke: A circular or ovoid stroke drawn in the counter-clockwise direction. So if the scribe draws a letter o like this, ⟲, it is a counter-clockwise stroke.

- cross-stroke: a horizontal stroke crossing a stem relatively close to the center of the stem.

- downstroke: a single movement stroke proceeding from top of the writing area toward the bottom. These are usually thicker than upstrokes.

- headstroke: a horizontal stroke crossing a stem near the top of a letter, such as the upper stroke of an E.

- left-handed stroke: a stroke where the pen touches down to the right and strokes toward the left.

- otiose stroke: a symbol which has no meaning. An example would be a suspension which does not symbolize an actual suspended letter. For example, "the word stokē in this sentence has an otiose stroke over the letter e, since the word is intended to be 'stoke,' not 'sroken' or 'stokem.'"

- right-handed stroke: a stroke where the pen touches down to the left and strokes toward the right.

- upstroke: a single movement stroke proceeding from bottom to top. Upstrokes are usually thin, at least by comparison to downstrokes.