Assorted Short Definitions

- [ ] (square brackets)

- A symbol found in the majority of critical editions, including e.g. Westcott & Hort and the UBS edition. The purpose of brackets is to indicate a high degree of uncertainty whether the text found within the brackets is original. For example, the UBS edition, in Mark 1:1, has the final words [υιου θεου] in brackets because they are omitted by, among others, ℵ* Θ 28.

The one problem with the bracket notation is that it can only be used for add/omit readings. Where two readings are equally good, but one substitutes for the other, there is no way to indicate the degree of uncertainty expressed by the brackets. This has caused some editors (e.g. Bover) to avoid the use of brackets; these editors simply print the text they think best.

The third course, and probably the best in terms of treating all variants equally, is to do as Westcott and Hort did and have noteworthy marginal readings. But this policy has not been adopted by modern editors. - Abschrift

- German for "copy, duplicate," and used to refer to manuscripts that are copies of other manuscripts. Normally symbolized by the superscript abbreviation abs. Thus 205abs is a copy of 205, and Dabs1 (Tischendorf's E) and Dabs2 are copies of D/06. Only about a dozen manuscripts are known to be copies of other manuscripts, though more might be recognized if all manuscripts could be fully examined (it is unlikely that there are any other papyrus or uncial manuscripts which are copies of other manuscripts, but few minuscules have been examined well enough to test the matter, and the number of lectionaries so examined is even smaller.)

- Acanthus

- A name for a border or boundary illustration (e.g. ❦ or ❁), often the flowering vines surrounding a text. Despite the name, it generally will not resemble an acanthus plant. The name seems to be more commonly used in descriptions of medieval Latin manuscripts (often secular) than Biblical.

- Accidental

- An element of the text of a particular manuscript which is not of textual significance. So, for instance, the difference between Δαβιδ and Δαυιδ is not of great importance; it may be the personal preference of the scribe, and in any case it was likely abbreviated at some point in the manuscript's history. So accidentals are generally not regarded as having genetic significance. Items regarded as accidentals in non-biblical textual criticism include spelling, punctuation, and capitalization; in the Greek NT, we could add accents and (probably) breathings. Variants which are not accidentals are called "substantives."

- Allograph

- In the usage of Nelson Goodman, a document whose original can be perfectly reproduced, as opposed to a work such as a painting which cannot be exactly recreated. (Note that, just because an allograph can be perfectly reproduced does not mean that it has been perfectly reproduced. In a sense, what an allograph is an object which we can check to see if it matches another copy.) For more discussion, see Archetypes and Autographs.

- Anagrammatism

- More often known as metathesis. It refers to copying letters out of order, e.g. ATE for EAT or TAR for RAT.

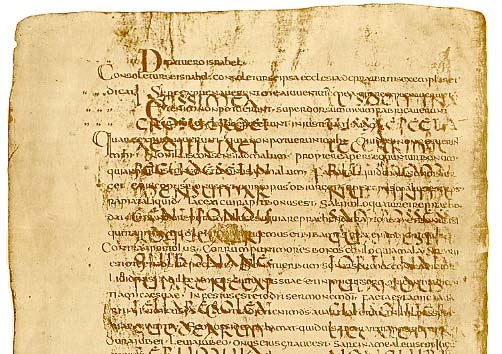

- Atlantic Bible

- So called not because it was written near the Atlantic but because of their large size -- a bible for the Greek giant Atlas. The term refers to extremely large Bibles produced in northern Italy starting in the eleventh century, with the format later copied elsewhere. The Codex Gigas (gig of the Old Latin) is regarded as an Atlantic Bible, although the contents are not entirely Biblical. It is said to have required two men to carry!

For another example of an Atlantic Bible, see the so-called Great Bible of Richard II, which was in fact probably owned by Richard II's successor Henry IV (reigned 1399-1413). This book, British Library MS. Royal 1 E IX, is .63x.43 meters (25x17 inches) and has 250 folios. The text is a Vulgate of the complete Bible plus the Gospel of Nicodemus, with colored decorations on most pages and some beautiful illustrations; the illuminations are thought to be by Herman Scheerre. The British Library has placed digital images on the web, to be found at http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Royal_MS_1_E_IX. Another Atlantic Bible, also in the British Library, is Egerton 617+Egerton 618 (a two volume Bible), which is .44x.29 meters (17x11.5 inches) -- clearly not as big as the examples above, but still not something you hold in your hand!

For something so large and inconvenient, Atlantic Bibles seem to have been fairly common, at least based on the fact that the UCLA library alone has four different fragments it lists as Atlantic Bibles: University Research Library MSS. 1/XI/Ita/3, 1/XI/Ita/5, 1/XI/Ita/12, 2/XII/Ita/13. (All are Vulgates, not Greek Bibles.)

Not all large, heavy volumes were Biblical. The Vernon Manuscript of Middle English romances and poetry (most of it religious, but not Biblical) currently weighs about 22 kg/49 lbs; it has lost quite a few leaves, and very likely been trimmed, so it originally must have weighed at least 27 kg/60 lbs. It gives us some indication of the format of these works: it is about 39 cm. by 54 cm., written mostly in three columns per page but with some parts in two, making for very wide columns; there are about 80 lines per page. The closely related Simeon Manuscript, which seems to have come from the same school and to have contained many of the same works, had even larger page dimensions, 39 by 59 cm., although it has lost so many leaves that we cannot really say how heavy it originally was. Frankly, Atlantic volumes were not just a pain to carry, they were a pain to read. But they stored a lot of information in a relatively small space.

A secular book of similar size might be known as a coucher book. - Atticism

- The conforming of language to the standards of Attic Greek. The New Testament is written in koine Greek (of varying quality, with Mark and the Apocalypse the worst, and Luke/Acts and Hebrews most literary). As time passed and spoken Greek evolved from Koine to Byzantine forms, there was a tendency to apply the rules of pre-Koine Greek, especially as used in Athens. The obvious temptation was to apply this standard of "proper" Greek to the New Testament (and also to the Septuagint).

- Authoritative Reading

- A term used by Ronald B. McKerrow and W. W. Greg for a reading "which may be presumed to derive by direct descent from the manuscript of the author." In other words, a reading not created by an editor.

- Banderole

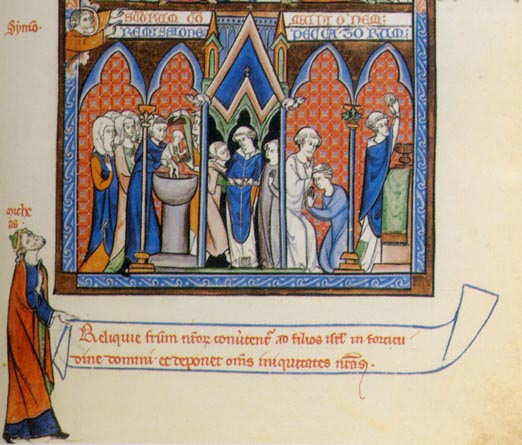

- A banderole is a feature of an illuminated manuscript allowing for comments beside the text. It is much like the "speech balloons"" in a modern comic strip. The illustration at right shows an example. This is a portion of a page of "the Rheims Missal," originally written shortly before 1300 and now in Saint Petersburg. The illustration is of church ritual, and in the margin we see the New Testament prophet Simon (Symo⋅) and the Old Testament prophet Micah (micheas). Micah is holding a banderole.

- Bas-de-page

- An illustration at the bottom of a page (hence the name). The illustration may not be related to the contents of the page. The term is rarely used in New Testament studies, but is fairly common in dealing with medieval manuscripts.

- Bat Book

- A modern term used by Peter Gumbert to describe books whose leaves were folded after the book was bound so as to take up less height and width (although obviously more depth) -- so-called because it unfolded its wings like a bat. The writing covered the whole page; the folds did not represent separate writing areas. When the book was read, the pages were unfolded so that the whole page could be used. The purpose presumably was to make a book small enough to fit in a small pocket or space while still allowing for large pages. We see a few small instances of this today in books with foldout maps. A few dozen bat books were cataloged by Gumbert; although I know of no Bibles in this format, it was sometimes used for religious works.

- Best Text Editing

- Best Text Editing means editing using one base manuscript and deviating from it only in extraordinary circumstances. Thus this is a strong form of editing from a copy text. This is by contrast to what George Kane calls Direct Editing (which see), which is fairly close to what New Testament critics call reasoned eclecticism (although I'd consider Kane's version much more methodologically rigorous).

- Bibliography

- Although we usually use the word "bibliography" for a list of books cited,

in textual criticism it has a different use -- for the "study of books."

In recent years, the "new bibliography" has resulted in a great deal of

insight into printed books such as the works of Shakespeare. The amount of detail bibliographic

work requires is amazing. Bibliographers study the paper used in printing (something

that New Testament critics might want to imitate more closely), the way the quires

are organized and bound (ditto), the amount of text on each page (which can tell us

something about the order the pages were typeset and perhaps about who typeset them;

see casting off copy),

the differences between individual printed copies

(since books were often corrected in mid-run but the bad pages still used), the way

the distinct impressions of pages were collated (e.g. if copy A has the first version

of page 34, and copy B has the second version, does that mean that A has an

"older" text? What if, on page 36, it's B that has the older copy?), the way

they were bound, and much more. If author's manuscripts exist, the paper of those

may be examined (e.g., although the author's draft of Frankenstein is now

formed into loose sheets, examination of the paper and signs of binding marks

show that these pages originally formed two notebooks). This sort of work

sometimes influences textual decisions in the books studied, and it consistently

reveals more about the printing history. Not all of the tools of bibliography

are useful in New Testament criticism, since many apply only to printed editions

(and, often, in printed editions of which we have multiple copies), but it is

a field that New Testament critics perhaps should be more aware of.

In New Testament criticism, bibliography overlaps paleography and codicology. To give an obvious example, it can tell us the direction of manuscript transmission. If we are convinced, e.g., that 1505 and 2495 are copies of each other (they aren't, but they're close; it is possible that one is a copy at several removes of the other), but we don't know which is the original and which the copy based on their texts, then bibliography can come to our aid. Since 1505 is from the twelfth or thirteenth century, and 2495 from the fourteenth or fifteenth, 1505 must be the ancestor and 2495 the descendant. - Bifolium, Bifolia

- Technical term for a single sheet folded in half (i.e. in folio form). Thus a bifolium contains two leaves or four pages. A group of bifolia are usually bound together to form a quire.

- Book Hand

- Term used in contrast to Documentary Hand. A term for a writing style considered suitable for, and attractive when used in, a book. Book hands were often more elaborate than documentary hands, and often took more time and effort to write -- e.g. book hands usually did not join letters, unlike documentary hands, which were often cursive. In the early New Testament period, book hands were more likely to be uncial or majuscule, but by the second millenium, this had changed -- in Latin writings in particular, both upper and lower case were used in book hands; the key was simply the lack of joined letters and, perhaps, the use of more strokes -- e.g. 𝖙𝖍𝖎𝖘 𝖜𝖔𝖚𝖑𝖉 𝖇𝖊 𝖆 𝖇𝖔𝖔𝖐 𝖍𝖆𝖓𝖉; 𝓉𝒽𝒾𝓈 𝓌ℴ𝓊𝓁𝒹 𝒷ℯ 𝒶 𝒹ℴ𝒸𝓊𝓂ℯ𝓃𝓉𝒶𝓇𝓎 𝒽𝒶𝓃𝒹. It is not unusual to find book hands in the body of a text, with marginalia in a documentary hand, especially if the marginalia were added casually instead of being part of a standard collection of glosses.

- Brevigraph

- A name for a particular sort of abbreviation in which a single symbol is used for more than one letter. An obvious example would be & for Latin et; Greek had ϗ for και; in Old English, before the advent of Arabic numerals, 7 was often used for and.

- Cadel

- Used to describe the decorations (in particular, animals) drawn as part of decorative initials extending above or below the margin of a page.

- Cancel

- Part of a manuscript or book marked for deletion, or (in particular), the replacement for that page. A famous cancel occurs in the Old Latin codex Vercellensis (a/Beuron 3) of the Old Latin: the original ending of Mark has been cut out and replaced by a leaf with a partial Vulgate text of the verses. This added leaf, almost certainly inserted to replace a text that lacked Mark 16:9-20, is a cancel.

In printed books, we often find canceled leaves in only some copies of an edition. It appears that, in many instances, a mistake was found after some copies were printed, and the already-printed sheets were used although the page was corrected and later copies had the corrected version. If a mistake was bad enough, but the printing was advanced, we may see pages already bound in quires cut out, and inserts added. - Carpet Page

- A characteristic feature of illuminated Celtic manuscripts. A carpet page is a page with no text, just an elaborate pattern like a carpet. Some carpet pages are built around a cross motif, but most of the more elaborate ones are not. The Book of Durrow (7th century) has a carpet page of spirals within wheels. The Lindisfarne gospels has a carpet page which actually looks like a carpet: A rectangular outline (although with ornaments at the cornets and images of birds at the center of each side), a border, and a circle-within-a-square motif in the center.

- Cast Off/Casting Off Copy

- A term from the era of printing rather than the manuscript age, but it has significance for textual criticism of relatively modern works, and perhaps also for early editions of fathers and the like. It refers to a method of typesetting a book in quires, in which the pages were set out of order.

Consider, for instance, a standard four-sheet quire, which has pages 1-16. If you examine the page numbers, pages 1 and 16 are on the same side of the same sheet. On the other side of that sheet are pages 2 and 15. The next sheet has pages 3 and 14 on one side, 4 and 13 on the other. The third sheet has pages 5+12 and 6+11; the innermost sheet is 7+10 and 8+9.

(If you want to know which pages go on the same side of the same sheet, there is a simple rule: take the number of pages in the quire and add one; call this N. For example, if you have a 16-page quire (four sheets), then N=17. If you have a 20-page quire (five sheets), then N=21. And so forth. For any sheet x in the quire, it will be pairec with page N-x. So if you have a 16-page quire, and you want to know which page goes on the same sheet as page 4, then N=17, x=4, and the page that goes with page 4 is 17-4=page 13. If you want the page that goes with page 6, that's 17-6=page 11.)

Now imagine that you want to set this 16-page quire from front to back (the technical term for this is seriatim typesetting). First you set page 1, then page 2, and so on. When do you get to start actually printing? Depending on whether you are doing single-sided printing or double-sided, you won't get to start until you've set at least the first nine pages, if you print single-sided, or when you're through page 10 if you're printing double-sided. That's because it's not until you've finished page 9 that you've completed an entire side of a sheet (in this case, 8+9), and not until you've completed page 10 have you completed both sides of a single sheet (8+9 and 7+10).

This has two problems -- or did, in the days of hand typesetting. First, you can't start printing until the compositor is more than half done, so your printers may be sitting around doing nothing. Second, ten pages of type (plus enough extra type to do pages 11-16) is a lot of type, and type, which required lead and antimony and tin (the last in particular being expensive) wasn't cheap. Many printers didn't have enough type to allow them to print an entire quire all at once.

The solution was to "cast off copy." That is, instead of setting the pages in the order 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6..., to set whole sheets at a time -- so to set pages 1+16, which go on the same sheet, and then 2+15, the reverse of that sheet -- and then typeset 3+14 and 4+13, and print them, and while that's going on, disassemble the type used for pages 1+16 and 2+15 and prepare it for the next job. And so on.

The obvious advantage of cast off copy was that it meant that the printer needed far less type; it was often more efficient for the pressmen as well (although a really good shop manager could see to it that they were kept busy -- the real problem was the lack of type). The disadvantage is probably obvious: Someone had to estimate exactly how much material would go on each page, and assign it to the compositor, and, somehow, the compositor had to make it all fit. If the estimate was off, the compositor either had to find ways to fit extra copy on his page (tricky) or make a shortage of copy fill the sheet without looking too spread out.

Note that this is the same problem that we see scribes have in estimating the size of a single-quire codex.

We see signs of both these problems in the First Folio of Shakespeare, e.g. -- if there is too much copy to fit on a page, the compositor may shorten speech prefixes (letting him get more type on a line), or combine lines of verse on a single line; if there is too little copy, he may spread the words out and break lines that do not need to be broken. In a few cases, it may even be that the compositor omitted a few lines, or made up new ones (it has been suspected that this happened in King Lear, where we have two very different versions of the text, though this is not the most widely-accepted explanation). For the sort of textual scholar who is trying to reconstruct Shakespeare's autograph right down to the punctuation and line breaks, this problem obviously has serious implications!

To minimize the effects of such mis-estimation as far as possible, it appears to have been the practice in at least some cases to start with the middle sheets of the quire -- so, e.g., in the case above, of a 16-page quire, to first typeset pages 8+9, then 7+10, then 6+11, and so forth. This had the advantage that one never had to guess the length of the full sixteen pages, just the first eight, and it also meant that pages 8-16 (more than half the quire) would be properly typeset and all the text on those pages at least would fit the available space properly. This also meant that, once the first page of the quire was set, it would be easy to give different parts of the master manuscript to two different typesetters (since the pages would not overlap), allowing the type to be set more quickly. The down side is that it means that the first page of the quire -- the one a potential customer would see first! -- was the last one typeset, and any mistakes in determining how much copy to set on each page would be likeliest to show up on the first page. An example where this may have taken place is the National Library of Scotland copy of the "Gest of Robyn Hode;" this work (badly typeset by a compositor who very likely was not fluent in English) is a metrical romance, in verse, and most of it is set as poetry, but the first page is set in continuous type as if it were prose -- clearly because there was more copy than would fit on the page.

Another obvious case is the Shakespearean First Folio edition of Much Ado About Nothing. Pages 120-121, the last two pages of the play, are on the last page of quire IL and the first page of quire L. Page 120, the last page of a quire, appear to be properly set; much of it is set as prose, but there is a song set in verse, and a number of blank lines. Page 121, the first page of a quire, is incredibly compressed; there are no blank lines at all, and stage directions are almost all on the same line as text; in some cases, the compositor seems to have left out space after punctuation. Even at a distance, you can tell the difference between the pages; page 121 is a much darker page.

There are of course many variations on casting off copy. In the Shakespearean First Folio, for instance, the quires were of three sheets rather than four, reducing the potential amount of error per sheet (fortunately, since the folio pages were large and contained a lot of type -- a four-sheet quire might have been too long to be managed); this was feasible only because the Folio was printed on paper, not vellum, so there was no issue of assuring that hair and flesh sides faced each other. - Catchword

- An important concept in bookbinding, which can matter when trying to reassemble a damaged manuscript. Codices were, of course, copied off in quires, and it was the task of the binder to put the quires in order. The catchword was intended to help with this process. When a scribe finished copying a quire, he would write, at the bottom of the last page of the quire, the first word of the text on the next quire. So if, for instance, someone were copying "Hamlet" (for whatever reason), and the great soliloquy were at the bottom of the page, so that "Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to" were the last words on one quire, and "suffer" the first word of the next, the bottom of the last page would look something like this (catchwords were often written vertically in the far margin:

Enter Hamlet

HAMLET:

To be, or not to be -- that is the

question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to

S

U

F

F

E

R

The use of catchwords spread throughout Europe during the twelfth century; prior to that, quires were usually numbered or assigned a letter. - Chapbook

- In popular usage, refers to any small volume, normally sold unbound, containing just a few dozen pages, although it must have more than one page -- a booklet rather than a book. But it is a technical term in publishing -- for a 12mo/duodecimo book -- one with 24 pages. This involves a complicated format of four folds (which would normally produce a 32-page book). The tables below show the fold layout and the numbers of the resulting pages (note: there are some geometric complications here -- properly, the inner side should be mirror imaged horizontally -- but I'm trying to make this as easy as possible!)

Outer Side

fold 2 fold 3 Fold 4 --4-- --5-- --12-- Fold 4 Fold 1 --21-- --20-- --13-- Fold 1 Fold 4 --24-- --17-- --16-- Fold 4 --1-- --8-- --9-- fold 2 fold 3 Inner Side

fold 2 fold 3 Fold 4 --3-- --6-- --11-- Fold 4 Fold 1 --22-- --19-- --14-- Fold 1 Fold 4 --23-- --18-- --15-- Fold 4 --2-- --7-- --10-- fold 2 fold 3

So if we list which pages go on the front and back of each page, we getSeen from Outer Side

fold 2 fold 3 Fold 4 --4--

+

-3---5--

+

-6---12--

+

-11-Fold 4 Fold 1 --21--

+

-22---20--

+

-19---13--

+

-14-Fold 1 Fold 4 --24--

+

-23---17--

+

-18---16--

+

-15-Fold 4 --1--

+

-2---8--

+

-7---9--

+

-10-fold 2 fold 3

Note that there are two significant complications with this format. One is that it's hard to set up. Setting folio pages is easy -- all the pages are set up and placed in the forme right-side up, and it's easy to know which pages go together (if m is the number of pages in a quire, then page n pairs with page 4m-n+1). An octavo is harder (some pages are upside-down) but still straightforward. Nothing is simple in a duodecimo quire! -- instances of getting the pages badly disordered are known. And even if one sets the pages in the forme properly, problems still arise with the folding -- to fold a page in half is easy. But to fold in thirds (as in fold 2 above, and arguably fold 3) is very difficult and takes special care. Chapbooks were useful in that they allowed the creation of inexpensive booklets, but they were none too easy to set in type. - Chrysography

- The process of writing in gold -- mixing powdered gold with some sort of binder and using it as an ink.

- Classes of Errors

- Errors are everywhere. Humans are fallible; that's just the way it is. But

errors fall into different classes or types. The most obvious classes are

"deliberate" versus "accidental" -- that is, where a scribe

thinks there is something wrong with his text and consciously tries to correct

it, versus where a scribe just goofs.

But another set of classifications that doesn't get as much attention is classification based on the means of copying. A text may be copied in many different ways. It may be copied from one manuscript to another. It may be copied orally in either of two ways: the speaker may be working from memory or from a written text, and the hearer may be copying it down or memorizing it. Or a text may be typeset, or it may be typed on a typewriter. Each of these will produce different classes of error. By classes of error I mean the sort of error most likely to occur. As an example, there is a line in Shakespeare's King Lear (III.vii.63 in the Riverside edition; III.vii.65 in the Signet; III.vii.71 in the Yale; in the New Pelican, which prints two versions, it's III.vii.66 of the quarto text, III.vii.62 of the folio) where the quarto reads dearne (derne, a now-forgotten word meaning "hidden") while the folio reads sterne (stern). Both readings make sense. (All the editions I have accept "dearne;"; but Signet mis-glosses as "dread"; Yale prints "dern" and glosses as "dreary," so it has both the spelling and the meaning wrong; the New Pelican quarto version also spells it "dern" and mis-glosses as "dreadful.") I too think "dearne" much more likely to be original, but the point for our purposes is that neither error (that is, dearne being replaced with stearne or vice versa) is likely to happen in either oral tradition or manuscript copying -- no Elizabethan would change "stearne" to the rare word "dearne"; and while the typesetter might have been tempted to change "dearne," the word he would think of probably wouldn't have been "stearne." Where this error does make sense is in early typesetting -- in the earliest known English typesetting box, the ligature st was located in the type case right next to d. So a typesetter reaching for a d could easily pull an st, or vice versa. Thus the derne/sterne confusion is a very reasonable accidental error in typesetting, and completely unreasonable (at least as an accidental error) in any other form of transmission.

So when we see a particular error, it is worth considering how it came about.

• If the means of copying is Oral Transmission, we can expect to see errors of hearing, e.g. ημας and υμας being confused.

• If the means of copying is Manuscript-to-Manuscript copying -- widely believed to be the norm for New Testament manuscripts -- we are likely to see more errors based on easily confused letters, e.g. ΑΛΛΑ being read as ΑΜΑ or vice versa.

• If the method of copying involves manual typesetting, common mistakes involve letters next to each other in the type case. The example derne/sterne, described above, is typical.

It's worth noting that, in these instances, it matters whether the word is in upper or lower case. For instance, it is easy to interchange lower case "tap" and "top," because the letters a and o are next to each other in the case. But upper case A and O are not next to each other, so "TAP" and "TOP" are not accidental versions of each other (although the compositor might have misread an a as an o, or the reverse, in his manuscript source). In the case of "TAP," reasonable mistakes are MAP and SAP, since M and S respectively directly above and to the left of T (LAP and NAP are at diagonals to T, so those are also possibilities, although somewhat less likely). We might also see TIP (I is to the lower right of A); there are no likely errors for P.

• If one is copying on a typewriter, obviously the most likely errors are Errors Involving Adjacent Letters, so we might e.g. see "five" and "give" confused. This raises the interesting thought that such errors might even occur in the autographs of authors who typed their words.

This point may seem esoteric in the context of copying manuscripts, but this does not automatically follow, since we have reason to believe that there were some manuscripts copied from dictation. So any given manuscript may contain errors based both on easily confused letters and on errors of hearing. If we see a manuscript which contains several errors of hearing (say, ημας for υμας and τε for δε), and we come to a situation where we are not sure of the source of an error, we should be more willing to attribute the harder-to-explain errors to that cause; but if we come to an instance where we see a series of errors likely based on errors of sight (e.g. ΑΜΑ for ΑΛΛΑ and Κ̅ϲ̅ for Κ̅ϵ̅), we should be more willing to suspect other errors of sight. - Clear Text Edition

- A term for a critical edition in which the text and apparatus are printed separately, generally without any indication in the text of where the reading is uncertain. The purpose of such an edition is to show the text as openly as possibly, without interference. For those interested primarily in the text, this is obviously helpful; for those who are interested in how the text is constructed, it is generally not helpful.

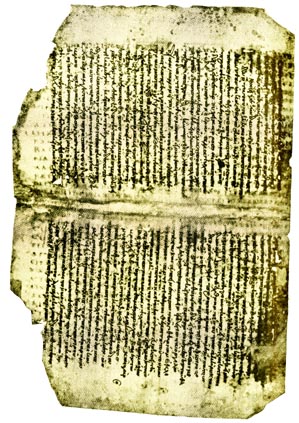

- Codex

- Plural codices. As used in NT circles, the characteristic format of Christian literature. The Christian church adopted this format almost universally in its early years, at a time when both Jews and pagan writers continued to use scrolls. (The earliest papyrus codices, in fact, seem to have been cut from scrolls, and not at the places where the leaves of the scroll were joined together; one can occasionally see the joins in the middle of a leaf of a papyrus codex.) Among known Christian manuscripts, all but four seem to havebeen written in codex form (the four exceptions, 𝔓12, 𝔓13, 𝔓18, and 𝔓22, are all written on reused scrolls; there is thus no known instance of a scroll being deliberately prepared for use in Christian literature).

The codex was in fact what moderns think of as a book -- a series of leaves folded and bound together, usually within covers. Codices could be made of parchment or papyrus (or, of course, paper, once it became available). Whichever writing material was used, a series of sheets would be gathered and folded over, meaning that each sheet yielded four pages. These gatherings of leaves are normally referred to as quires.

Many of the earliest codices consisted of only a single quire of many pages. Examples of single-quire codices include 𝔓5 (probably), 𝔓46, and 𝔓75. Single-quire codices, however, are inconvenient in many ways: They do not fold flat, they often break at the spine, and the outside edges of the page are not even. Also, it was often difficult to open them enough to read the text near the inner margin of the middle pages. Still more troublesome is the fact that the scribe had to estimate, before the copying process began, how many leaves would be needed. If the estimate was inaccurate, the codex would be left with blank pages at the end, or -- even worse -- a few extra pages which would have to be somehow attached to the back of the document. (Compare the problems involved in typesetting using cast off copy.) As a result, it became normal to assemble books by placing smaller quires back to back. This can be seen as early as 𝔓66, which uses quires of from four to eight sheets (16 to 32 pages). Quires of four sheets (16 pages) eventually became relatively standard, although there are many exceptions (B, for example, uses five-sheet quires).

It is sometimes stated that the Christians invented the codex. This is of course not true; the word itself is old (Latin caudex properly refers to a tree trunk, hence to anything made of wood, and hence came specifically to mean a set of waxed tablets hinged together. E. Maunde Thompson, An Introduction to Greek and Latin Palaeography, p. 51, notes that Ulpian in the third century makes reference to literary codices). Indeed, we have quite a few examples of pagan literature on codices in the early centuries of the Christian Era; David Diringer (The Book Before Printing, p. 162) surveyed known manuscripts from Oxyrhynchus (as of half a century ago), noting that of 151 pagan documents known to him from the third to sixth centuries, fully 39 were codices. And Jerome mentioned a number of pagan codices in his possession (Thompson, p. 53).

It has been suggested that, prior to the church's adoption of the form, the scroll was for literary works intended to be read while the codex was for reference works. This is supported by the fact that a large fraction of the earliest pagan codices are reference works (medical manuals, legal treatises, grammatical books). C. H. Roberts in fact suggested that the author of the Gospel of Mark was used to these sorts of reference manuals, and so wrote the original copy of his gospel in codex form -- and hence popularized the format.

But if the church did not invent the codex, it does seem to have been responsible for the popularity of the codex format (e.g. in Diringer's example, of 82 Christian documents, 67 were codices), and scrolls seem to have remained the preferred format for pagan literary works after codices were adopted for most other purposes. There is even an instance (in the Stockholm Codex Aureus) of an illustration in which Matthew the Evangelist is shown holding a scroll and an angel carrying a codex; this is thought to mean that Matthew is holding the Law of the Old Testament but is being handed a codex which will represent the New.

We should also note that a sort of proto-codex existed in the form of the orihon.

We observe that the codex has both advantages and disadvantages for literature, especially when dealing with papyrus codices. It requires less material (which may be why the Christians adopted it), and it's easier to find things in a codex. But it's rather harder to write (since one must write against the grain on a papyrus, or on the rough side of a piece of vellum), and one also has to estimate the length of the finished work more precisely. The latter disadvantages probably explain why the Christians were the first to use the codex extensively: They needed a lot of books, and didn't have much money; pagans didn't need so many books, so they felt the disadvantages of the codex more, and the advantages less.

Codices have another advantage, though it wasn't realized at the time: They survive abuse better. Being flat, there are no air pockets to collapse, and they protect their contents better. At Herculaneum, thousands of scrolls were discovered, rolled up and damaged by the conditions that buried them. Centuries of efforts to open and read them accomplished little except to ruin the documents involved. Had the documents been stored in codex form, their outer leaves would have been destroyed but the inner would likely have been in much more usable shape.

The sections of codices were usually numbered. But unlike modern books, it was not individual pages that were numbered, but whole quires. This suggests, to me at least, that the primary purpose was not to make it easier to find things in the volumes but rather to tell the binder the order of the quires. It was not until about the fourteenth century that actual page numbering became common, and even then, it was tied to quire numbering (e.g. the first page would not be "1" but "A.i" and the seventeenth, which would be the first of the second quire in a typical book, would not be "17" but "B.i"). - Coherence-Based Genealogical Method

- Commonly abbreviated "CBGM." A method developed by Gerd Mink to try to evaluate manuscript evidence and reconstruct the original text. The method is based on full collations of selected witnesses, and because it uses vast amounts of data, it requires computers and databases to perform its computations; it constructs relationships based on "coherence" -- which is an undefined term based on agreements over a large block of text based on comparison of many manuscripts.

Mink has described the method in several journal articles, as well as the article "Contamination, Coherence, and Coincidence in Textual Transmission: The Coherence-Based Genealogical Method (CBGM) as a Complement and Corrective to Existing Approaches," in Holmes & Wachtel, editors, The Textual History of the Greek New Testament. At present, however, the most convenient explanation is probably Tommy Wasserman and Peter J. Gurry, A New Approach to Textual Criticism: An Introduction to the Coherence-Based Genealogical Method, References for Biblical Study, Society of Biblical Literature (Atlanta)/Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft (Stuttgart), 2017.

The method is being used to create the text of the new Editio Critica Maior, in a complex process involving the collation of many manuscripts, the assessment of their text, and then, ultimately, human examination of the results.

Mink's article in Holmes & Wachtel defines a number of useful terms on pp. 143-144 -- although, ironically, it does not define "coherence" in any way, and what is the point of the method if we don't know what "coherence" is? But let's take some of the terms and try to paraphrase or clarify.

* Connectivity is not used as, say, a mathematician would use it, to describe links in a network; rather, it is a term for genetic relatedness -- but it is not a statistical measure; rather, it derives from two completely unrelated sources. One is overall rate of agreements -- a particular reading in two manuscripts are connected if the manuscripts are close kin. The other is the old classical rule of agreement in error. Because these two measures are so different, it will be seen that connectivity is a descriptive term, not a mathematical one.

* Genealogical coherence is Mink's fancy new idea. Unfortunately, since he hasn't defined "coherence," the title doesn't mean anything. But the goal is to define how manuscripts relate based on including the direction of local stemma. In essence, what high genealogical coherence means, or is supposed to mean, is that there is a high degree of relatedness that doesn't just come about from overall agreements. These are more significant agreements. Manuscripts with relatively weak pre-genealogical coherence may still have an important relationship revealed by their genealogical coherence. It must once again be stressed, however, that Mink has not demonstrated that this means anything. It's just a number.

Genealogical coherence is actually determined by looking at places where two manuscripts disagree and determining which reading is most likely to have given rise to the other. To take a specific example, if 205 and 205abs agree (in whatever section of text we're reading and whatever variants we're using) in 95% of cases (that is, have 95% pre-genealogical coherence), and in every case where 205abs differs from 205, it is an obvious haplography, then 205 give clear signs of being an ancestor, or close to an ancestor, of 205abs. Thus the reading "flows" from 205 to 205abs. If there arises a case where most of the "flows" from one manuscript to another are in one direction, then the suggestion (unproved, of course) is that where there is an exception, it represents a contamination in the "downstream" manuscript. This, then, is how the CBGM accounts for mixture -- as long as there isn't too much of it.

It will be noted that flow direction is a distinctly different operation from Lachmann's agreement in error -- it is based on disagreements, but directional disagreements. If all disagreements were demonstrably directional, the power of the tool would be clear -- but it ultimately suffers from the same problem as Lachmann's agreement in error: in Lachmann, you had to know which readings were errors. For Mink, you have to know which direction a variant "flows."

* Global Stemma is the term Mink uses for what just about everyone else simply calls a stemma, i.e. a family tree of manuscripts.

* Initial Text is the term Mink and others now use for the archetype (as opposed to the autograph). See Archetypes and Autographs.

* Optimal substemma is complicated.... Any group of two or more witnesses have multiple possible historical/textual relationships (A is descended from B, B is descended from A, both are descended from a common ancestor, etc.). So all these relationships are possible stemma/substemma. The trick is to figure out which one is right. Mink's method for calculating this is to choose the stemma in which "the number of ancestors is reduced to the minimum." In other words, if you could, say, produce the text of 1881 by suitably combining the texts of 1739 and a Byzantine manuscript, or by combining 6, 323, and 1739 (either of which would produce effectively every reading found in 1881), then you prefer the former as the optimal stemma; it requires only two sources. This certainly sounds good -- it sounds like an application of parsimony, which is a very powerful tool -- but there are two potential problems. First, there is the problem of directionality -- if C looks like a mix of A and B, can we be sure that it mixes A and B, rather than that B is in fact a mixed version of C? Second, suppose that there are two possible stemma, one heavily mixed (C has half the readings of A and half the readings of B) and one minimally mixed (C has 98% of the readings of D and 2% of the readings of E), which is optimal? Mink, rather than resolve the situation, prefers to settle this matter by hand. Given his lack of a real algorithm, I think that is the right choice -- but a real algorithm is better! And it should be emphasized that, in fact, the optimal substemma may not be the actual stemma of a manuscript, or even of its text, because the entire goal of a substemma is to minimize ancestors -- but in fact a late manuscript, in particular, may have many ancestors. It is perfectly possible that a manuscript with many Byzantine readings and a relative handful of non-Byzantine readings -- a 104 or a 157, say -- may have had an Alexandrian ancestor which, on multiple occasions, was poorly conformed to the Byzantine text via various Byzantine lines, whereas the optimal CBGM stemma would probably consist of one Alexandrian manuscript with a minor influence and a single Byzantine manuscript that was the major stemmatic ancestor.

* Parsimony is a term used by Mink -- incorrectly. (I should probably bold and highlight that statement and put it in flashing print. If you talk to a mathematician about Mink's idea of parsimony, you're going to have problems.) A parsimonious process is one that requires the fewest assumptions or changes -- and Mink correctly uses this in connection with trees. (That is, Mink is probably correct to assume that, if a manuscript is clearly mixed, and several sorts of trees serve equally well to explain the mixture, then the tree involving the fewest number of sources is the most parsimonious tree.) But on p. 153 of Holmes and Wachtel, Mink states that "A scribe uses few rather than many sources" and states that "this assumption follows from... the rule of parsimony." But this is not a parsimonious assumption; "a scribe uses many sources" and "a scribe uses few sources" are equally parsimonious assumptions, and no assumptions about the number of sources is more parsimonious still. This sort of error comes up several times. I think Mink's assumption is usually true, but it can't be justified on parsimony and it would be better for having evidence. And since Mink can't prove it, he should probably test what happens if he assumes the contrary.

* Pre-genealogical coherence simply represents the rate of overall agreements between two manuscripts -- percentage agreement. This is the sort of agreement every other study in the past has used (although usually over smaller samples). It does not classify readings and does not attempt to evaluate whether one reading came before another. Mink notes that high agreement in PGC implies close relationship, but does not explicitly note a second point: that merely having a relatively low PGC does not mean two manuscripts are unrelated. For instance, if a manuscript were compiled by taking alternate readings of B and D, and the PGC of that manuscript were computed against B and D, the result would be fairly low. This even though the manuscript is descended from B and D! PGC by itself only measures relationship between witnesses that have not been heavily mixed -- which is why Mink tried to create a method that goes beyond it.

* Stemmatic ancestor is basically a fancy term for "genetic ancestor or something like it." So, for instance, (I would assume) 1739 is a stemmatic ancestor of 1881 -- 1881's text looks much like 1739's, except that a lot of 1739's readings have been replaced by Byzantine readings. So 1881's text combines readings of 1739 and 𝕸. Can we assume 1881 is actually descended from 1739 -- that is, that there was once a manuscript which was a copy of 1739, and another manuscript that was a copy of that, and that eventually the outcome of that process was 1881? Probably not; 1881 could have been descended from a text similar to 1739 (say, 0243 or 0121) rather than 1739 itself. But the text that 1739 represents is ancestral to 1881.

* Stemmatic coherence is "coherence" between manuscripts which are linked as ancestor and descendant in an optimal substemma. Yet again, since coherence is not defined, this term is not defined either.

* Textual flow is another term Mink handwaves into existence without definition. It seems to mean "genetic relationship" -- readings pass ("flow") from one witness to another as the witness is copied.

The technique is too complicated to really explain here; it is sort of statistical, but not really; is sort of genealogical, but not really; and claims to produce a sort of a stemma -- but not really. For starters, it depends in significant part on assessments of local stemma. Then, too, insofar as it creates a stemma, it creates one from the top down, which very much violates the whole principle of stemmatics. And the result isn't even a stemma anyway! It's just a set of relationships. So at no point do you get a true stemma where you can say, "this is the earliest reading of branch α, this is the earliest of branch β, this is the earliest of branch γ."

Also, the CBGM does not allow for lost ancestors. So in the diagram on p. 97 of Wasserman/Gurry, for instance, it is proposed that C is descended from 1739 -- a fifth century MS. descended from one of the tenth century! Similarly, on p. 105, we find 614 shown as the ancestor of 2412, even though 2412 is the earlier manuscript. It is true that 614 and 2412 are very closely akin; this has been known since Clark collated 2412. They are very likely sisters -- but 614 cannot be the parent. Similarly, while it is certainly true that 1739 and C have a special kinship, closer to each other than the rest of the so-called Alexandrian manuscripts, it must be through lost ancestors, not through any extant witnesses, and if there are lost ancestors, then why don't we draw the linkage through them? The answer given by Wasserman and Gurry (p. 108) is that the stemma they offer isn't a stemma codicum, that is, a real stemma (which is true), but rather a stemma of texts -- meaning that 614's text can be an ancestor of 2412's text (which is true in a way -- 2412 could have been copied from an ancestor of 614) -- but this misses the whole point of a stemma!

And, as Wasserman/Gurry admit on p. 114, "Contamination remains a problem." In other words, mixture -- the reason that no one has been able to produce a New Testament stemma (the real kind, not the CBGM kind) is still with us; the CBGM has not resolved it.

It should also be noted that there does not seem to be any actual evidence that this works -- there has been no testing. It is all based on Mink's assumptions. Some of them are very parsimonious assumptions, which is good. But there are too many of them! And while the CBGM accounts for mixture, it does not explain it (e.g., to again take the case of 1739 and 1881, the CBGM would doubtless say that 1881 descends from 1739 plus some Byzantine text -- but does not tell us if it is descended by mixture from 1739, by correction, or if it is a Byzantine text corrected toward 1739 along the lines of 424c, or something else).

There is also a curious lack of a goal. Yii-Jan Lin, The Erotic Life of Manuscripts, p. 156, says that "at first glance, this approach to texts seems quite postmodern" -- "the Ausgangtext as constructed by these scholars is ahistorical, having no descendants and hailing from no real, original environment. It represents all extant texts, of every date, compressed and analyzed at one moment of analysis...." Lin also objects to its iterative nature. I have no problem with iteration -- but I would go beyond Lin (who backs off from his postmodernist critique) to say that the whole thing exists at a high level of abstraction. But the text, and all phases of the text, are real, even if they have been lost: There was an ancestor of all texts; there was an ancestor of the Byzantine text (admittedly that ancestor may have been the archetype, but it existed), there was an ancestor of every manuscript now extant, and of all their ancestors and descendants now lost. These were real texts, existing in single copies -- given a time machine, they could be seen. Maybe they can't be reconstructed, but they can be inferred.

Although the method is taking textual criticism -- or at least Münster -- by storm, I must admit to deep disquiet about the whole thing. And this is not because I object to mathematical or computer methods; I was making manuscript databases before Mink started publishing his ideas. But the way Mink describes other methods is simply perverse -- e.g., to justify his method, he uses Hutton's notion of text-types, or at best Streeter's, neither of which is the one I would use; both assume the solution. This is setting up a straw man so that he can pretend to have something superior. There is no question that he does have something better than Hutton. Well, anyone with half a brain has something better than Hutton! With all that data and all that computing power, we could do this right and create an actual stemma, as Stephen C. Carlson has demonstrated, and the CBGM would be redundant -- and we wouldn't have to depend on all those arbitrary local stemma. Obviously very many others disagree with my assessment. (Lin, p. 123, suggests that the objection to trying to find a stemma is that it would reduce the need for textual critics to use their other skills. I will admit to thinking the same -- but I would also point out that having a stemma does not mean that there is less need for internal evidence; it just means that the internal evidence must be evaluated in light of the stemma.) - Cola and Commata

- An arrangement of the text in sense lines rather than continuously. So, for example, Romans 14:19-20, if written in cola et commata, would probably look something like this:

So let us then seek what makes for peace

and for mutual strengthening.

Do not, for the sake of food,

destroy God's work.

All things are indeed clean,

but it is wrong for you

to make others fail because of what you eat.

Note that cola et commata are based on whole ideas rather than just syllable counts; they are not (e.g.) Homeric stichoi. Some lines are long, some short.

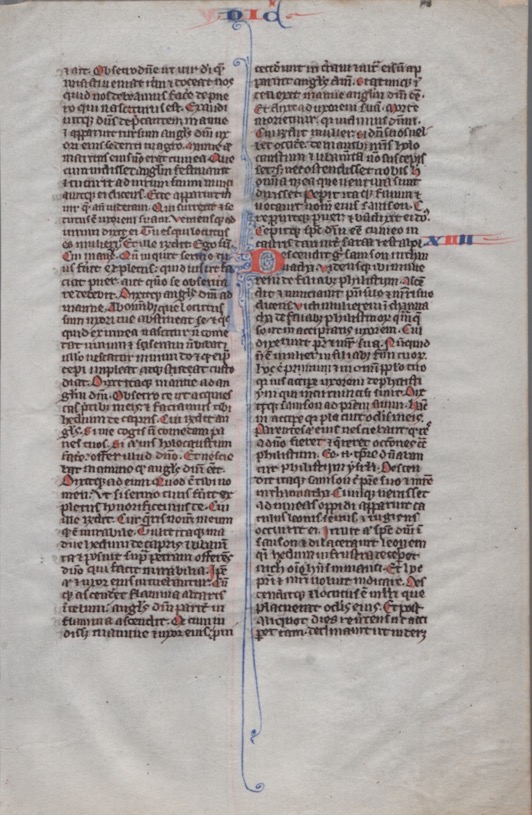

Cola and commata are the standard for Latin texts; both major critical editions of the Vulgate use this format. It is much rarer in Greek manuscripts, which tend to be continuously written, but the Euthalian edition was in sense lines, and the poetic books of the Old Testament were often written as poetry rather than prose.

In Latin, the use of cola became so common that they were sometimes abbreviated by the use of colored letters to mark the beginnings of lines, alternating red and blue. Thus, for instance, where the "classic" format of Psalm 84 (from LXX) would look like this:

In compressed cola, this would look like Victor filiorum core canticum Placatus es Domine terrae tuae Reduxisti captivitatem Iacob Dimisisti iniquittem populo tuo.V ictor filiorum core canticum

Placatus es Domine terrae tuaereduxisti captivitatem Iacob

dimisisti iniquittem populo tuo

The use of cola et commata is sometimes attributed to Jerome, and he does seem to have promoted the use of the format in the Vulgate. But he certainly wasn't responsible for the use of cola in the Greek Bible, in the poetical books of the Old Testament or in the Euthalian edition. - Collateral Descent

- A term also found in genealogy. In essence, it means "related but not in direct line." So a father and daughter are related by direct descent, not collateral descent, while a pair of cousins are collateral relatives. Similarly, in Paul, D and Dabs are related by direct descent (D is the parent of Dabs), but D and G are related by collateral descent (both have a common ancestor, but neither is a parent, or grandparent, or even great-great-grandparent of the other; some sort of mixture and alteration has intervened). Theoretically, of course, all manuscripts of a particular corpus are collaterals of each other, but the term will generally not be used once the relationship becomes sufficiently remote.

- Compilatio

- The process of deciding the contents of a volume. At its most elementary, it consists of just deciding which books to include and their order (e.g. "the four gospels in the order Matthew, Mark, Luke, John"). But it also includes, for instance, assembling an order for The Canterbury Tales (several different medieval editors did this, producing manuscripts with different orders). Even in cases where the main text is certain, choices must be made about the page layout (deciding, e.g., the number of columns). And compilatio also includes deciding which reader helps and marginalia are included -- e.g. whether to include the Eusebian apparatus in the gospels, or section heads or chapter summaries. Or a drawing that one scribe means as an ornament might be interpreted by another as signalling the end of a text. Aspects of compilatio can therefore influence a text -- if a manuscript in one column is copied from one with two columns, there might be some contamination between columns. Or if there are section headings of some sort, those might contaminate the text, or if they are taken from a manuscript which disagrees with the main run of the text being copied, they can influence the text. An even more obvious example comes in poetic manuscripts -- Middle English poetic manuscripts very often drew lines between rhyme words. For example, lines 1-4 of the poem "Worldes blisse, have good day" would be written as shown below:

Worldes blisse, have good day, ────┐

Now fram min herte wand away. _____⌋

Him for loven min hert is went, ────┐

That thurgh his side spere rent; ___⌋

It will be evident that, if a scribe sees an indication that two words are supposed to rhyme, and they don't, the scribe will be tempted to do something to make them rhyme! So a good textual critic should have some knowledge of manuscript formats, and of the decisions made during compilatio. - Complex Type/Variant

- A term created by Greg to contrast with "simple" variants. A run of text is simple if it either has no variants (other than singular variants) or if a variant is binary -- two and only two readings; it is complex if it has more than two. Greg classifies these according to the number of different readings: A Type 1 reading is one where there are no (non-singular) variants; a Type 2 reading is one where there are two and only two variants. These are the simple types of variants. A reading of Type 3 or higher is a complex variant. So, e.g. the variant in Matthew 8:28 has four readings: Γαδαρηνων/Γερασηνων/Γεργσηνων/Γαζαρηνων. The last of these is singular (it's supported only by ℵ*), so there are three non-singular readings. That makes this a Type 3/complex reading. By contrast, the variant between Ασα and Ασαφ in Matthew 1:7 is a Type 2/simple variant (because there are only two readings). The basic difference between simple and complex variants lies in genealogy: In a simple variant, you merely have to decide which variant best explains the other. But, in a complex variant, you need to construct what Kurt Aland would have called a "local genealogy" -- an historical reconstruction of which variants might give rise to the others. The two thus require rather different types of criticism.

- Complutensian Polyglot

- For more than half a century after the first printed Latin Bible, there was no printed copy of the Greek New Testament. The first to take the matter in hand was Cardinal Francisco Ximénes de Cisneros.

It is worth noting that the Complutensian was not the first attempt at a polyglot. It appears that the great printer Aldus Manutius set up samples for some sort of an edition, and in 1516, a Pentaglott Psalter was published in Genoa with texts in Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, Latin, and Arabic. (Why start with a psalter? Don't ask me. The psalter was very popular, but also very long....) But Ximenes deserves credit for both attempting the first New Testament, and the first full Greek Bible, and the first polyglot to include the New Testament. Cisneros started the project in 1502; some say it was in celebration of the birth of the heir to the Habsburg dynasty, the future Emperor Charles V.

The place of the printing was Alcalá (Complutum). The Old Testament was to include Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, with Aramaic (the Targum of Onkelos) as a footnote to the Pentateuch; the New Testament was given in Greek and Latin, with additional scholarly tools. The editors were an interesting and distinguished group -- Ælius Antonius of Lebrixa, Demetrius Ducas of Crete, Ferdinandus Pincianus, Diego Lopez de Zuñiga (Stunica, the fellow who eventually had the controversy with Erasmus over 1 John 5:7-8), Alfonsus de Zamora, Paulus Coronellus, and Johannes de Vergera (the last three converted Jews, and Ducas presumably the descendent of Byzantine Christians, so they represent a wide range of viewpoints. It is interesting to note that different modern texts give different lists of editors -- not just spelling the names differently but adding or omitting various people; I've included every name I've found).

The planning for the volume, as mentioned, began in 1502, though it took almost a dozen years for printing to begin. There were six volumes, and the whole project is estimated to have cost 50,000 ducats -- a large fraction of the revenues of the entire diocese of Alcalá;.

The printer was Arnald William de Brocario. It is reported that 600 copies were printed, of which three were on vellum, the rest on paper. Almost a hundred of them still survive. Volume V, containing the New Testament, was finished early in 1514. (It is worth noting that Paul precedes the Acts in this volume.) Volume VI, with a lexicon, index, and other aids, was completed in 1515, and the other four volumes, containing the Old Testament (with, of course, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical books) came off the press in 1517. Ximenes unfortunately died late in that year. Papal approval was much delayed (some have said the Pope wouldn't approve the book until borrowed manuscripts were returned, or that the death of Ximénes caused problems, but we don't really don't know the reason); the imprimatur came in 1520, and the volumes were finally made available to the public apparently in 1522.

The appearance of the Greek New Testament has sparked much discussion. (Interestingly, the Greek of the Septuagint is in a more normal Greek style, and uses a font similar to those produced by Aldus Manutius for his Greek books.) It is sometimes said that nothing like the font used for the New Testament has ever been seen. This is exaggerated. What is unusual is not the font but the orthography. There are no rough or smooth breathings, and the accents are peculiar. (Make you wonder if Demetrias Ducas spoke an odd dialect or something. Scrivener, to be sure, denies this, pointing out that Ducas composed some Greek verse which was perfectly well-written and pointed, so he could write "proper" Greek.) The font itself is not particularly unusual. Metzger-Text, p. 85, says the "type used in the New Testament volume is modelled after the style of the handwriting in manuscripts of about the eleventh or twelfth century, and is very bold and elegant." Bold and elegant is certainly is -- but also much simplified from hand-written models. It is very much closer to an earlier Greek typeface, used by Sweynheym and Pannartz in 1465 to print Lactantius. There are differences, to be sure (the delta in the Polyglot is more uncial, while the Lactantius is like a minuscule delta; the Lactantius uses only one form of the letter sigma, the Lactantius uses an uncial gamma and a very strange beta). But the feeling of the two is very similar; the Complutensian is simply a much more refined version of the same style.

The interesting question is why the compositors changed fonts between testaments; why, after using such a beautiful Greek face for the New Testament, did they shift to the ugly Aldine fonts for the Old? The Aldine fonts were immensely complicated (see the article on Books and Bookmaking); was it merely that they hadn't managed to cut such a font in time? Were there complaints about the modern-looking fonts? (And if so, why, given that no one except the publishers had seen the books?) Was it something about the source manuscripts? (This seems unlikely, but since the manuscripts are unknown, it's perhaps possible.) Did the publisher bring in new typesetters who could set the more elaborate Aldine faces and keep track of the accents? My guess is the latter, but it is unlikely that we will ever know.

As mentioned, the manuscripts underlying the Complutensian Polyglot have never been identified, though there is no doubt that the text is largely Byzantine. (Scrivener, p. 180, says that there are 2780 differences from the Elzevir text -- 1046 in the Gospels, 578 in Paul, 542 in Acts and the Catholic Epistles, 614 in the Apocalypse -- which about the same as the number of differences between Elzevir and the true Majority Text. And Scrivener says there are only about 50 typographical errors.) The editors did thank the Pope for use of manuscripts, but there are chronological problems with this; it is likely that, if the Vatican supplied Greek manuscripts, they were used only for LXX, not the NT. (Several scholars say explicitly that two Vatican manuscripts were used for LXX, perhaps those numbered 108 and 248.) Stunica makes explicit reference to one Greek manuscript in the New Testament, but this manuscript (Tischendorf/Scrivener 52a) is lost.

Scrivener notes some interesting and unusual readings of the polyglot's Greek text (e.g. Luke 1:64 αυτον διηρθρωθη και ελαλει with 251 and a handful of other manuscripts; Luke 2:22), and observes that some have seen similarities to 4e, 42, 51. There seems to have been no real attempt to follow up these hints, probably because the Polyglot had no real influence on later printed editions. I strongly suspect that, if anyone really cared, we could identify most of these manuscripts now, simply because we have much more complete catalogs of variants.

It may be that relatively little attention was devoted to the Greek text by the editors. That the Latin was considered more important than the Greek is obvious from the handling of 1 John 5:7-8 (and even more from the comment on the Old Testament that they had placed the Latin in the middle column, between Hebrew and Greek, like Jesus between the two thieves), but Scrivener denies that the Greek was systematically conformed to the Latin -- he believes (Plain Introduction, fourth edition, volume II, p. 177) that the crack about the two thieves was an indication that the editors though the Greek and Hebrew corrupted, and so trusted the Latin more.

The Greek text of the New Testament isn't the only peculiar attribute of the Polyglot. The Hebrew of the Old Testament is not pointed according to the usual method; rather, it appears to conform to the Babylonian pointing. Manuscripts of this type are now few; it is likely that the Polyglot used some now-lost sources (unless, as with the Greek, the editors simply adopted their own pointing system). This would seem to imply that the Complutensian is more significant for Old than New Testament criticism. - Conflation, Conflate Text

- A conflate text is one which is made up by combining the readings of multiple sources. So, for example, if one were to print the text of B verbatim, except that one added Mark 16:9-20 from some other source, the result would be a conflate copy. (Thus every New Testament edition from Erasmus to the UBS edition is conflate.) Or in Luke 24:52, where 𝔓75 ℵ B C* L etc. read ευλογουντες, D reads αινουντες, and A Cc K W etc. read αινουντες και ευλογουντες, the reading αινουντες και ευλογουντες is a conflation of the readings of B and of D.

Conflation is the act of conflating texts.

In one of those curious cases where New Testament textual criticism differs from classical, the phenomenon of two texts becoming intermingled is more often called "mixture" in a New Testament context. One might perhaps try to draw a fine distinction between mixture and conflation (e.g. that mixture happens over many generations as texts are compared, but conflation happens only once), but in practice the two terms can probably be treated as synonyms.

In popular usage, the word "collation," which is a comparison of texts, is sometimes used for "conflation," which is a combination of texts. This is very much to be deplored, as it leads to grave misunderstandings about the nature of texts and how they were edited. - Conjunction

- A term for readings where two or more sources agree. Thus, for instance, ℵ and B are in conjunction in omitting Mark 16:9-20. Where texts disagree, they are in disjunction. The term is typically used in classical textual criticism in constructing a stemma.

- Contamination

- In simplest terms, the introduction of alien elements into a text. Thus

the act of contamination results in mixture, or a conflate

text. Sometimes "contamination" is used to refer to a text that

has been deliberately conflated, but this is not always so.

Although the term "contamination" on its face would seem to imply that the resulting text is inferior, this is not always the case. All the term means is that the text is not a pristine descendant of its ancestral text. 424c, for instance, is a contaminated text which is much better (that is, closer to the original text) than the uncontaminated Byzantine text of 424*. - Coucher Book

- A term which has had different meanings over the centuries. In current usage, the terms refer to a very large book, also known as an lectern book or a ledger book (spelled "ligger" in some Middle English references), or, if it is a Biblical volume, an Atlantic Bible. It is called a "coucher book" because it was read on a couch or lectern -- i.e. it was "couched" (from French couchier).

The term itself seems to have originated in the fifteenth century (first recorded 1434; "ledger book" is attested from 1418) and in the Latin west, so it will not commonly be used to refer to Greek manuscripts. Originally it was used simply for service volumes such as missals and breviaries, which were generally couched in one place because that was where they were used.

The usage for large volumes is more recent, and seemingly accidental: starting in the nineteenth century, because it was assumed that a book left on a lecturn must be very large -- too big to hold in the hand -- it was assumed that all coucher/ledger bibles were big. The coucher book most familiar to students of the New Testament will surely be the Codex Gigas (gig of the Old Latin). Students of Middle English literature will know of the Vernon Manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Eng. Poet. A.1), which was called "a vast Massy MS" by a 1697 cataloger; this religious volume is about 39 cm. by 54 cm. (and may have been slightly larger as originally bound); it currently weighs about 22 kg./49 lbs, and given that it has lost about a fifth of its pages, must initially have weighed about 27 kg./60 lbs. The even larger Simeon Manuscript (British Library, MS. Additional 22283), which is about 39 cm. by 59 cm., now contains rather less than half its original leaves, so we can hardly estimate its original weight, but it too was heavy. Manuscripts this large were not common, because they required such large sheets of parchment, but neither were they especially rare. Perhaps the largest number of coucher books were missals and antiphonals -- the latter needing to be large so that both parties of performers could see the writing (which obviously was large in such cases; in non-service books, the writing was not necessarily so large).

Although the words used for these volumes are recent, the idea of these large books was clearly well-known in antiquity; a number of illuminated psalters show an image of groups of monks singing around a coucher book (presumably a lectern bible or other service book). This image is usually found at the beginning of Psalm 97 Vulgate (Psalm 98 MT), "Cantate Domino canticum novum" ("Sing to the Lord a new song").

The term "coucher" seems to have been used mostly in northern England, while "ledger" is southern. There was an order, early in the Reformation, to destroy the old (Catholic) coucher books, which perhaps opened the way for the new definition; it soon was used of parish registers and cartularies instead of service books. (Ironically, most of these were books of rather small size.)

There does seem to have been an increase in large-format books starting around the fourteenth century. The goal seems to have been to have all materials relevant to a particular topic gathered in one place. - Alexandrian Critical Symbols

- The scholars of the ancient Alexandrian library are often credited

with inventing textual criticism, primarily for purposes of reconstructing

Homer. This is a somewhat deceptive statement, as there is no

continuity between the Alexandrian scholars and modern textual critics.

What is more, their methods are not really all that similar to ours

(they would question lines, e.g., because they didn't think Homer could write

an imperfect line). But their critical symbols will occur on occasion

in New Testament works as well as (naturally) classical works. In

addition, Origen used some of the symbols in the Hexapla.

In fullest form, the Alexandrians used six symbols:

Symbol Name Purpose - Obelus Oldest and most basic (and occasionally shown in other forms); indicates a spurious line. (Used by Origen in the Hexapla to indicate a section found in the Hebrew but not the Greek. For this purpose, of course, it had sometimes to be inserted into the text, rather than the margin, since the LXX, unlike Homer, was prose rather than poetry.) ⊱ or > Diple Indicates a noteworthy point (whether an unusual word or an important point of content). Often used in conjunction with scholia, e.g. to note a word used only once, or to mark errors in the text. This role was also played by a marginal chi, χ, which E. G. Turner calls the most common of all the critical symbols. ⸖ periestigmene

(dotted diple)Largely specific to Homer; indicates a difference between editions ※ Asteriskos A line repeated (incorrectly) in another context (the location of the repetition was marked with the asterisk plus obelus). (Used by Origen to note a place where the Greek and Hebrew were not properly parallel.) ※ - Asterisk plus

obelusIndicates the repetition of a passage which correctly belongs elsewhere (the other use, where the passage is "correct," is also marked, but only with the asterisk) ⊃ Antistigma Indicates lines which have been disordered χ chi See under the Diple, >. - Cruciform, cruciform text

- Text written in the form of a cross (crux). The most famous example

of this is probably the gospel manuscript

047, but there are a number

of lectionaries which use this format. Those who wish to see examples

of the form may consult Jeffrey C. Anderson, The New York Cruciform

Lectionary, College Art Association/Pennsylvania University Press, 1992.

This include more than sixty illustrations of cruciform texts, with

discussion, although unfortunately the commentary is devoted almost

entirely to the preparation of the manuscript and its artwork rather

than its text.

It is usually explained that cruciform manuscripts are rare because they are wasteful of parchment, and this would certainly be true if they resembled a genuine cross used for crucifixion, which is tall and narrow. But a cruciform manuscript is typically shaped more like a plus sign + than a proper cross. Typically it will look something like this:

=== === ===== ===== ===== === ===

Thus the text, at its narrowest, occupies about 60% of the page, and also about 50% of its height is written at full width. That means that about 80% of the writing area contains text, and only 20% is blank -- and even that 20% can be used for illustrations and such that would otherwise eat into the text. Cruciform manuscripts are inefficient, but not so inefficient as to make them impossibly expensive had there been demand. Clearly there wasn't demand.

Also, although full-blown cruciform manuscripts are rare, it is not uncommon to find parts of a manuscript in cruciform. Often the format is used for some sort of reader help, such as the table of contents, the prologues to the books, or the Eusebian letter explaining the canon table. Or, if there was room, the last page of a gospel might be written in cruciform. - Crux

- A difficult reading, a place where editors disagree very much. Broadly speaking, these fall into four classes:

1. A case where the textual tradition is united or nearly, but in which the text appears to be nonsense (this is very common in criticism of the Hebrew Bible and in classical texts, although somewhat less so in the New Testament). An obvious example is 1 Samuel 13:1, where Saul is said to be one year old and to have reigned two years -- despite the fact that he was, first, an active king, and second, a father and even a grandfather when he died. Pretty impressive for a three-year-old! Obviously the verse cannot be understood as it literally reads.

2. A case where internal evidence is not entirely decisive and the witnesses are so closely divided that no reading appears superior. An example of this might be 1 Thessalonians 2:7, where ΕΓΕΝΗΘΗΜΕΝΝΗΠΙΟΙ (εγενηθημεν νηπιοι) is found in 𝔓65 ℵ* B C* D* F G I 104* 1962 and ΕΓΕΝΗΘΗΜΕΝΗΠΙΟΙ (εγενηθημεν ηπιοι) in ℵc A Cc Dc K L P 6 33 81 256 365 436 1319 1739 1881 2127. Here UBS prefers the first reading, presumably on the basis of external evidence (although I for one would not consider a reading supported by A 33 81 1739 1881 and family 1319 to be much more weakly attested than one supported by ℵ* B C* D* F G I 1962), but the New Revised Standard Version chose to print "gentle."

3. A case where there are so many readings, all so weakly attested, that there is no clearly superior reading. Here an example might be Galatians 1:8, where UBS prints the reading of D2 6 33 256 263 1319 2127 pm, ευαγγελιζητι υμιν, but there are other readings attested by 𝔓51-vid B H 1175 1739 2200, by ℵ* b, by ℵ A 81, by K P 075 365 439 1881 pm arm, by D*, by F G Ψ, and others.

4. A case where the internal evidence clearly supports one reading but the external evidence against it is overwhelming. An example of this, to me, is 1 Corinthians 13:3. The reading καυθησωμαι is ungrammatical and would invite correction, and a single letter change would produce both the reading καυχησωμαι of 𝔓46 ℵ A B 0150 33 1739 and the reading καυθησομαι of C D F G L 81 104 263 436 1175 1881*. Thus, on internal grounds, καυθησωμαι is the best reading. But the attestation of καυθησωμαι is pitiful -- K Ψ 6 256 365 1319 1573 1739c 1881c 1962. Thus there is no reading which is entirely satisfactory.

Of course many cruxes combine traits of these types of problems. The key point is that these are readings where editors have great difficulty with the text or, especially if the reading is of the first type, with its interpretation. - Cumdach

- The Irish name for a "book shrine." These were often highly elaborate protective covers. Sometimes the very case was revered, but they could also be effective guards for the contents -- there is at least one instance of a book in its cumdach being tossed into the sea and later being recovered essentially intact. The covers of the most valued manuscripts were often decorated and even inlaid with gold or jewels.

- Cyrograph

- A sort of "document validation" found in some manuscripts where there were supposed to be two copies. This probably doesn't affect New Testament manuscripts very often, but it could involve such things as a Biblical bill of sale. In a cyrograph, the two copies of a writing were written on the top and bottom of the same piace of parchment or paper, like this:

This is the long, elaborate, complicated

and nitpicky text of my document

CYROGRAPH

This is the long, elaborate, complicated

and nitpicky text of my document

When the document was finished, it would be cut in two through the word CYROGRAPH (or whatever word was used to validate the document). If ever there was need to validate the two halves, the two could be placed alongside each other. If the two halves of the cut message matched, then you could be (fairly) sure that you had both halves of the true original.

As time passed, cyrographs became even more elaborate. The indentures used for soldiers in the Hundred Years' War, for instance, didn't just cut the contract in half, they cut it in half in a zig-zag pattern. This made it even harder to forge a contract, and also made the identification of the two halves even more secure. - Diminuendo