New Testament Manuscripts

Uncials

Note: In the catalog which follows, bold type indicates a full entry. Plain type indicates a short entry, which may occur under another manuscript.

Additional note regarding the Great Uncials (especially ℵ A B C D): These manuscripts have simply been studied too fully for there to be any hope of a complete examination here, let alone complete bibliographies. The sections below attempt no more than brief summaries.

Contents: * ℵ (01) * A (02) * B (03) * C (04) * Dea (05) * Dp (06) * Dabs * Ee (07) * Ea (08) * Ep: see Dabs * Fe (09) * Fa * Fp (010) * Ge (011) * Ga: see 095 * Gb: see 0120 * Gp (012) * He (013) * Ha (014) * Hp (015) * I (016) * Ke (017) * Kap (018) * Le (019) * Lap (020) * Me (021) * Mp: see 0121 and 0243 * N (022) * O (023) * Pe (024) * Papr (025) * Q (026) * R (027) * S (028) * T (029) * Tg (Scrivener Tp): see 061 * Tk (Scrivener Tg): see 085 * U (030) * V (031) * W (032) * X (033) * Y (034) * Z (035) * Γ (Gamma, 036) * Δ (Delta, 037) * Θ (Theta, 038) * Λ (Lambda, 039) * Ξ (Xi, 040) * Π (Pi, 041) * Φ (Phi, 043) * Ψ (Psi, 044) * Ω (Omega, 045) * 046 * 047 * 048 * 049 * 050 * 053 * 054 * 055 * 056 * 061 * 065 * 066 * 067 * 068 * 069 * 071 * 076 * 085 * 095 and 0123 * 098 * 0120 * 0121 and 0243 * 0122 * 0123: see 095 and 0123 * 0142: see article on 056 * 0130 * 0145 * 0206 * 0212 * 0219 * 0243: see 0121 and 0243 * 0253 * 0254 * 0259 * 0260 * 0261 * 0262 * 0263 * 0264 * 0265 * 0266 * 0268 *

Manuscript ℵ (01)

Location/Catalog Number

The entire New Testament portion, plus part of the Old and the non-Biblical books, are in London, British Library Add. 43725. (A singularly obscure number for what is one of the most important manuscripts in the world!) A handful of Old Testament leaves are at Leipzig. Originally found at Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai, hence the name "Codex Sinaiticus." A few stray leaves of the codex apparently remain at Sinai. ℵ is the famous Codex Sinaiticus, the great discovery of Constantine von Tischendorf, the only surviving complete copy of the New Testament written prior to the ninth century, and the only complete New Testament in uncial script.

Contents

ℵ presumably originally contained the complete Greek Bible plus at least two New Testament works now regarded as non-canonical: Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas. As it stands now, we have the New Testament complete (all in London; 148 leaves or 296 pages total), plus Barnabas and Hermas (to Mandate iv.3.6). Of the Old Testament, we have about 250 leaves out of an original total of some 550. Apart from the portions still at Sinai (which are too newly-found to have been included in most scholarly works), the Old Testament portion consists of portions of Gen. 23, 24, Numbers 5-7 (these first portions being cut-up fragments found in the bindings of other books), plus, more or less complete, 1 Ch. 9:27-19:17, 2 Esdras (=Ezra+Nehemiah) 9:9-end, Esther, Tobit, Judith, 1 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees (it appears that 2 and 3 Maccabees never formed part of the text), Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lament. 1:1-2:20, Joel, Obadiah, Jonah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Job.

Date/Scribe

Dated paleographically to the fourth century. It can hardly be earlier, as the manuscript contains the Eusebian Canons from the first hand, or at least from a scribe contemporary with the first hand. But the simplicity of the writing style makes a later dating effectively impossible.

Tischendorf was of the opinion that four scribes wrote the manuscript; he labelled them A, B, C, and D. It is now agreed that Tischendorf was wrong. The astonishing thing about these scribes is how similar their writing styles were (they almost certainly were trained in the same school), making it difficult to distinguish them. Tischendorf's mistake is based on the format of the book: The poetic books of the Old Testament are written in a different format (in two columns rather than four), so he thought that they were written by a scribe he called C. But in fact the difference is simply one of page layout; scribe C never existed. For consistency, though, the three remaining scribes are still identified by their Tischendorf letters, A, B, and D.

An interesting aspect of Sinaiticus is its severe plain-ness. Even Codex Vaticanus has occasional graphics (though a lot of them are pretty ugly) and a few instances of red ink. Sinaiticus has almost none. (This may not have been all bad. Sinaiticus is thought to have been in Palestine in the early Islamic era, and a manuscript which did not violate the Islamic ban of representations of living things perhaps had a better chance of surviving.)

Of the three, scribe D was clearly the best, having almost faultless spelling. A, despite having a hand similar to D's, was a very poor scribe; the only good thing to be said about him was that he was better than B, whose incompetence is a source of almost continual astonishment to those who examine his work.

The New Testament is almost entirely the work of scribe A; B did not contribute at all, and D supplied only a very few leaves, scattered about. It is speculated (though it is no more than speculation) that the few leaves written by D were "cancels" -- places where the original copies were so bad that it was easier to replace than correct them. (One of these cancels, interestingly, is the ending of Mark.)

It has been speculated that Sinaiticus was copied from dictation. This is because a number of its errors seem to be errors of hearing rather than of sight (including an amusing case in 1 Macc. 5:20, where the reader seems to have stumbled over the text and the copyist took it all down mechanically). Of course, the possibility cannot be absolutely ruled out that it was not Sinaiticus itself, but one of its ancestors, which was taken down from dictation. In the case of the New Testament, at least, it seems likely that it was not taken from dictation but actually copied from another manuscript.

Sinaiticus is one of the most-corrected manuscripts of all time. Tischendorf counted 14,800 corrections in what was then the Saint Petersburg portion alone!

The correctors were numerous and varied. Tischendorf groups them into five sets, denoted a, b, c, d, e, but there were actually more than this. Milne and Skeat believe "a" and "b" to have been the original scribes (though others have dated them as late as the sixth century); their corrections were relatively few, but those of "a" in particular are considered to have nearly as much value as the original text.

The busiest correctors are those collectively described as "c," though in fact there were at least three of them, seemingly active in the seventh century. When they are distinguished, it is as "c.a," "c.b," and "c.pamph." Corrector c.a was the busiest of all, making thousands of changes throughout the volume. Many of these -- though by no means all -- were in the direction of the Byzantine text. The other two correctors did rather less; c.pamph seems to have worked on only two books (2 Esdras and Esther) -- but his corrections were against a copy said to have been corrected by Pamphilius working from the Hexapla. This, if true, is very interesting -- but colophons can be faked, or transmitted from copy to copy. And in any case, the corrections apply only to two books, neither in the New Testament. There may have been as many as two others among the "c" correctors; all told, Tischendorf at one time or another refers to correctors c, ca, cb, cc, and cc*. These correctors also worked on Barnabas and Hermas, and are thought to have worked from a distinctly different exemplay.

Correctors d and e were much later (e is dated to the twelfth century, and d is from the eighth or later), and neither added particularly many changes. Indeed, no work of d's is known in the New Testament.

It is unfortunate that the Nestle-Aland edition has completely befuddled this system of corrections. In Nestle-Aland 26 and beyond, ℵa and ℵb are combined as ℵ1; the correctors ℵc are conflated as ℵ2, and (most confusing of all) ℵe becomes ℵc. It is understandable that the contemporary, nearly-indistinguishable correctors be lumped, but it would surely be clearer to cite ℵa, ℵc, and ℵe. Of course, NA26 does the same with, for instance, C and D.

(For more information about the correctors of ℵ, see the article on Correctors.)

There has been much dispute about where ℵ was written. Ceriani, who originally thought Syria a likely place, later suggested south Italy. Hort believed it was from the west, perhaps Rome. Harris preferred Cæsarea; although Ropes thinks there is no evidence for this, there are those Pamphilian correctors. Ropes and others support Egypt, very likely Alexandria. This suggestion is complicated by the fact that B and ℵ have different types, at least in Paul, and the B text goes with the Sahidic, so surely the B text is native to Egypt. On the other hand, ℵ goes with the Bohairic, so it too has a claim to Egyptian-ness. It would seem Egypt had two early text-types.

Description and Text-type

The history of Tischendorf's discovery of Codex Sinaiticus is told in almost every introduction to New Testament criticism; I will not repeat it in any detail here (especially since there is a great deal of controversy about what he did). The essential elements are these: In 1844, Tischendorf visited Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai. (Sadly, he did not do much to investigate the many fine minuscules at Mount Sinai, such as 1241 and 1881). At one point, he noted 43 sheets of very old parchment in a waste bin, destined to be burned. Tischendorf rescued these leaves (the Leipzig portion of Sinaiticus, all from the Old Testament), and learned that many more existed. He was not able to obtain these other leaves, and saw no sign of the manuscript on a second visit in 1853.

It was not until 1859, near the end of a third visit, that Tischendorf was allowed to see the rest of the old manuscript (learning then for the first time that it contained the New Testament -- complete! -- as well as the Old). Under a complicated arrangement, Tischendorf was allowed to transcribe the manuscript, but did not have the time to examine it in full detail. Tischendorf wanted to take the manuscript to the west, where it could be examined more carefully.

It is at this point that the record becomes unclear. The monks, understandably, had no great desire to give up the greatest treasure of their monastery. Tischendorf, understandably, wanted to make the manuscript more accessible (though not necessarily safer; unlike Saint Petersburg and London, Mount Sinai has not suffered a revolution or been bombed since the discovery of ℵ). In hindsight, it seems quite clear that the monks were promised better terms than they actually received (though this may be the fault of the Tsarist government rather than Tischendorf). Still, by whatever means, the manuscript wound up in Saint Petersburg, and later was sold to the British Museum.

There is at least one interesting sidelight on this, in that Tischendorf's story of his discovery has a clear historical precedent in the discovery of the Percy Manuscript. In around 1753, Thomas Percy was visiting his friend Humphrey Pitt when he discovered the maids burning a paper folio. (A much more reasonable thing to burn than a pile of parchments, which do not burn well!) Percy was able to rescue the century-old poetic miscellany, which eventually inspired him to publish his Reliques in 1765. [Source: Nick Groom, The Making of Percy's Reliques, Oxford, 1999, p. 6.] It almost makes you wonder if Tischendorf had read Percy's account. Happily, the parallels did not extend beyond that point: Percy edited, rewrote, and generally misrepresented his manuscript -- and the owners kept it hidden for many years so that it was impossible to know just how much he had ruined its contents. By contrast, Tischendorf published Sinaiticus with great precision.

However unfair these proceedings to the monks of Sinai, they did make the Sinaiticus available to the world. Tischendorf published elaborate editions in the 1860s, Kirsopp Lake published a photographic edition before World War I, and once the manuscript arrived in the British Museum, it was subjected to detailed examination under ordinary and ultraviolet light.

The fact that ℵ is both early and complete has made it the subject of intense textual scrutiny. Tischendorf, who did not pay much attention to text-types, did not really analyse its text, but gave it more weight than any other manuscript when preparing his eighth and final critical edition. Westcott and Hort regarded it as, after B, the best and most important manuscript in existence; the two copies made up the core of their "neutral" text. Since then, nearly everyone has listed it as a primary Alexandrian witness: Von Soden listed it as a member of the H type; the Alands list it as Category I (which, in practice, means purely Alexandrian); Wisse lists it as Group B in Luke; Richards classifies it as A2 (i.e. a member of the main Alexandrian group) in the Johannine Epistles, etc. The consensus was that there were only two places where the manuscript is not Alexandrian:

* the first part of John, where it is conceded

that it belongs to some other text-type, probably "Western," (Gordon D. Fee, in a study whose methodology I consider dubious -- one can hardly divide things as closely as a single verse! -- puts the dividing point at 8:38), and

* in the Apocalypse, where Schmid classifies it in its own, non-Alexandrian, type with 𝔓47.

The truth appears somewhat more complicated. Zuntz, analysing 1 Corinthians and Hebrews, came to the conclusion that ℵ and B do not belong to the same text-type. (Zuntz's terminology is confusing, as he refers to the 𝔓46/B type as "proto-Alexandrian," even though his analysis makes it clear that this is not the same type as the mainstream Alexandrian text.) The true Alexandrian text of Paul, therefore, is headed by ℵ, with allies including A C I 33 81 1175. It also appears to me that the Bohairic Coptic tends toward this group, although Zuntz classified it with 𝔓46/B (the Sahidic Coptic clearly goes with 𝔓46/B), while 1739, which Zuntz places with 𝔓46/B, appears to me to be separate from either.

This leads to the logical question of whether ℵ and B actually belong together in the other parts of the Bible. They are everywhere closer to each other than to the Byzantine text -- but that does not mean that they belong to the same type, merely similar types. There are hints that, in the Gospels as in Paul, they should be separated: B belongs to a group with 𝔓75, and this group seems to be ancestral to L. Other witnesses, notably Z, cluster around ℵ. While no one is yet prepared to say that B and ℵ belong to separate text-types in the gospels, the possibility must at least be admitted that they belong to separate sub-text-types.

In Acts, I know of no studies which would incline to separate ℵ and B, even within the same text-type. On the other hand, I know of no studies which have examined the question. It is likely that the two do both belong to the Alexandrian type, but whether they belong to the same sub-type must be left unsettled.

In Paul, Zuntz's work seems unassailable. There is no question that B and ℵ belong to different types. The only questions are, what are those types, and what is their extent? Zuntz's work is little help, but it would appear that the ℵ-type is the "true" Alexandrian text. 𝔓46 and B have only one certain ally (the Sahidic Coptic) and two doubtful ones (the Bohairic Coptic, which I believe against Zuntz to belong with ℵ, and the 1739 group, which I believe to be a separate text-type). ℵ, however, has many allies -- A, C, 33 (ℵ's closest relative except in Romans), and the fragmentary I are all almost pure examples of this type. Very many minuscules support it with some degree of mixture; 81, 1175, and 1506 are perhaps the best, but most of the manuscripts that the Alands classify as Category II or Category III in Paul probably belong here (the possible exceptions are the members of Families 365/2127, 330, and 2138). It is interesting to note that the Alexandrian is the only non-Byzantine type with a long history -- there are no 𝔓46/B manuscripts after the fourth century, and the "Western" text has only three Greek witnesses, with the last dating from the ninth century, but we have Alexandrian witnesses from the fourth century to the end of the manuscript era. Apart from certain fragmentary papyri, ℵ is the earliest and best of these.

The situation in the Catholic Epistles is complicated. The work of Richards on the Johannine Epistles, and the studies of scholars such as Amphoux, have clearly revealed that there are (at least) three distinct non-Byzantine groups here: Family 2138, Family 1739 (which here seems to include C), and the large group headed by 𝔓72, ℵ, A, B, 33, etc. Richards calls all three of these Alexandrian, but he has no definition of text-types; it seems evident that Amphoux is right: These are three text-types, not three groups within a single type.

Even within the Alexandrian group, we find distinctions. 𝔓72 and B stand together. Almost all other Alexandrian witnesses fall into a group headed by A and 33 (other members of this group include Ψ, 81, 436). ℵ stands alone; it does not seem to have any close allies. It remains to be determined whether this is textually significant or just a matter of defective copying (such things are harder to test in a short corpus like the Catholic Epistles).

As already mentioned, Schmid analysed the manuscripts of the Apocalypse and found that ℵ stood almost alone; its only ally is 𝔓47. The other non-Byzantine witnesses tend to cluster around A and C rather than ℵ. The general sense is that the A/C type is the Alexandrian text (if nothing else, it is the largest of the non-Byzantine types, which is consistently true of the Alexandrian text). Certainly the A/C type is regarded as the best; the 𝔓47/ℵ type is regarded as having many peculiar readings.

Other Symbols Used for this Manuscript

von Soden: δ2

Many critical apparatus (including those of Merk and Bover, as well as Rahlfs in the LXX)

refer to ℵ using the siglum "S."

Bibliography

Note: As with all the major uncials, no attempt is made to compile a complete bibliography.

Collations:

A full edition, with special type and intended to show the exact nature of the corrections, etc. was published by Tischendorf in 1861. This is now superseded by the photographic edition published by Kirsopp Lake (1911). And that in turn has been updated by the detailed scans at www.codexsinaiticus.org. The British Library has also released high-resolution scans, at http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_43725&index=3.

Sample Plates:

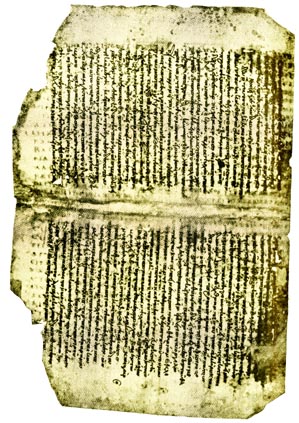

Images are found in nearly every book on NT criticism which contains pictures.

Editions which cite:

Cited in all editions since Tischendorf.

Other Works:

See especially H. J. M. Milne and T. C. Skeat, Scribes and Correctors of

Codex Sinaiticus (1938)

Manuscript A (02)

Location/Catalog Number

British Library, Royal 1 D.v-viii. Volumes v, vi, and vii (as presently bound) contain the Old Testament, volume viii the New Testament. Originally given to the English by Cyril Lucar, at various times patriarch of Alexandria and Constantinople. He had it from Alexandria, and so the manuscript came to be called "Codex Alexandrinus," but it is by no means sure that it had always been there. There is a colophon saying it was given to the Patriarchal cell in 1098, but the hand is very late (very possibly post-Lucar), so it is not considered very reliable.

Contents

A originally contained the entire Old and New Testaments, plus I and II Clement and (if the table of contents is to be believed) the Psalms of Solomon. As the manuscript stands, small portions of the Old Testament have been lost, as have Matthew 1:1-25:6, John 6:50-8:52 (though the size and number of missing leaves implies that John 7:53-8:11 were not part of the manuscript), 2 Cor. 4:13-14:6. The final leaves of the manuscript have been lost, meaning that 2 Clement ends at 12:4. Like the New Testament, the Old contains some non-canonical or marginally canonical material: 3 and 4 Maccabees, Psalm 151, Odes.

Date/Scribe

There is some slight disagreement about the date of A. A colophon attributes it to Thecla the martyr, who according to tradition was active in the time of Saint Paul (!), but this is clearly a later forgery, since; it may have been written by a Thecla, but not that Thecla. The late date of the note is shown by the fact that it is written in Arabic; Cyril Lucar himself reportedly wrote a Latin note mentioning the tradition that Thecla was the scribe -- but a fourth century Thecla, not the one from the Pauline era. (It claims that a colophon to this effect was in the lost pages.) The attribution to a fourth century scribe is barely possible. Although most experts believe the manuscript is of the fifth century, a few have held out for the late fourth. A very few have held out for later dates: Semler said seventh, and someone by the name of Oudin apparently placed it in the tenth century! (This was based on the inclusion of an alleged letter of Athanasius, which, it was claimed, must have been written in the tenth century because there were lots of forgeries written around that time. There is also another Arabic note signed Athanasius, who if it is anyone we've ever heard of, is believed to be the Patriarch Athanasius III, who was active in the early fourteenth century.) No scholar since the early nineteenth century has taken either of these claims seriously, however, and our knowledge of ancient manuscripts and their dating is vastly greater now.

Wettstein had a family story that it came to Alexandria from Mount Athos, but although the story was supposed to go back to Lucar's circle, there were several links of hearsay along the way.

The number of scribes has also been disputed; Kenyon thought there were five, but Milne and Skeat (who had better tools for comparison) suggest that there are only two, possibly three. (The uncertainty lies largely in the fact that part of the New Testament, beginning with Luke and ending with 1 Cor. 10:8, present a rather different appearance from the rest of the New Testament -- but when compared in detail, the hand appears extremely similar to the scribe who did the rest of the New Testament. Thus some think there is a change of scribes there, but others disagree. As far as I know, no one has suggested that the current binding combines parts of two different copies, perhaps written by the same scribe. The Apocalypse has been attributed to a third scribe.) Occasional letterforms are said to resemble Coptic letters, perhaps hinting at Egyptian origin, but this is not universally conceded.

A contains a significant number of corrections, both from the original scribe and by later hands, but it has not undergone the sort of major overhaul we see in ℵ or D or even B (which was retraced by a later hand). Nor do the corrections appear to belong to a particular type of text. On the whole, the corrections in the New Testament are minor.

The colophons at the ends of books are decorated (sometimes simply with borders, sometimes with very simply pen-and-ink illustrations); the borders are not very attractive and the illustrations, to my eye, worse; they don't show much evidence of real artistic skill, and certainly don't add much to the manuscript.

Description and Text-type

The story of how A reached its present location is much less involved than that of its present neighbour ℵ. A has been in England since 1627. It is first encountered in Constantinople in 1624, though it is likely that Cyril Lucar (recently translated from the Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria to that of Constantinople) brought it with him from Egypt. Lucar was involved in a complex struggle with the Turkish government, the Catholic church, and his own subordinates, and presented the codex to the English in gratitude for their help. The Church of Constantinople was disorderly enough that Lucar seems to have had some trouble keeping his hands on the codex, but it eventually was handed over to the English.

After arriving in Britain, it did have one brief adventure: During the English Civil War, there was threat of dispersal of the Royal Library (the core of what became first the British Museum then the British Library). When Librarian Patrick Young was allowed to retire, he took the Alexandrinus with him; it was finally returned to the Library in 1664. Given how erratic was the behavior of Cromwell's followers, that may have been just as well.

A is somewhat confounding to both the friends and enemies of the Byzantine text, as it gives some evidence to the arguments of both sides.

A is Byzantine in the gospels; there can be no question of this. It is, in fact, the oldest Byzantine manuscript in Greek. (The Peshitta Syriac is older, and is Byzantine, but it obviously is not Greek.) But it is not a "normal" Byzantine witness -- that is, it is not directly related to the Kx type which eventually became dominant. The text of A in the Gospels is, in fact, related to Family Π (Von Soden's Iκ). Yet even those who documented this connection (Silva Lake and others) note that A is not a particularly pure member of Family Π. Nor, in their opinions, was it an ancestor of Family Π; rather, it was a slightly mixed descendent. The additional elements seem to have been Alexandrian -- the obvious example being the omission of John 7:53-8:11, but A also omits, e.g., Luke 22:43-44 and (in the first hand) John 5:3. Westcott and Hort felt the combination of B and A to be strong and significant. We are nonetheless left with the question of the relationship between A and the rest of the Byzantine text. The best explanation appears to me to be that A is derived from a Byzantine text very poorly and sporadically corrected against an Alexandrian document (most likely not systematically corrected, but with occasional Byzantine readings eliminated as they were noticed in an environment where the Alexandrian text dominated). But other explanations are certainly possible.

(Ropes makes the observation that, in the Psalms, A seems to mix early and Lucianic elements, as it mixes a few early readings with Byzantine elements in the gospels. Since the Gospels and the Psalter were the most important service books of the church, they could occur together, so Ropes hints that the text of A is related in these two sections. But this depends on the relationship between "Lucian" and the Byzantine text, which is far from settled.)

The situation in the rest of the New Testament is simpler: A is Alexandrian throughout. It is not quite as pure as ℵ or B or the majority of the papyri; it has a few Byzantine readings. But the basic text is as clearly Alexandrian as the gospels are Byzantine. The Alands, for instance, list A as Category I in the entire New Testament except for the Gospels (where they list it as Category III for historical reasons). Von Soden calls it H (but Iκa in the Gospels).

In Acts, there seems to be no reason to think A is to be associated particularly with ℵ or B. It seems to be somewhat closer to 𝔓74.

In Paul, the situation changes. A clearly belongs with ℵ (and C 33 etc.) against 𝔓46 and B. This was first observed by Zuntz, and has been confirmed by others since then.

The case in the Catholic Epistles is complicated. The vast majority of the so-called Alexandrian witnesses seem to be weaker texts of a type associated with A and 33. (Manuscripts such as Ψ, 81, and 436 seem to follow these two, with Byzantine mixture.) The complication is that neither B nor ℵ seems to be part of this type. The simplest explanation is that the Alexandrian text breaks down into subtypes, but this has not been proved.

In the Apocalypse, A and ℵ once again part company. According to Schmid, ℵ forms a small group with 𝔓47, while A is the earliest and generally best of a much larger group of witnesses including C, the vulgate, and most of the non-Byzantine minuscules. In this book, the A/C text is considered much the best witness. Based on its number of supporters relative to the 𝔓47/ℵ text, one must suspect the A/C text of being the mainstream Alexandrian text, but this cannot really be considered proved -- there simply aren't enough early patristic writings to classify the witnesses with certainty.

Other Symbols Used for this Manuscript

von Soden: δ4

Bibliography

Note: As with all the major uncials, no attempt is made to compile a complete bibliography.

Collations:

The first publication of the manuscript was as footnotes to the London Polyglot. The symbol "A" comes from Wettstein. A photographic edition (at reduced size) was published by Kenyon starting in 1909.

The British Library has now published high-quality scans of the entire New Testament volume; available at http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Royal_MS_1_D_VIII&index=10

Sample Plates:

Images are found in nearly every book on NT criticism which contains pictures.

Editions which cite:

Cited in all editions since Tischendorf (plus Wettstein, etc.)

Other Works:

Manuscript B (03)

Location/Catalog Number

Vatican Library, Greek 1209. The manuscript has been there for its entire known history; hence the title "Codex Vaticanus." The catalog made by the Vatican Librarian Platina and his assistant Demetrius Lucensis in 1475 and supplemented in 1481 does not have catalog or shelf numbers (which were not established until 1620), but it refers in the list of Greek manuscripts to a copy of the "Testamentum antiquum et novum" on parchment The 1481 report says it is in three columns. This is the only Greek manuscript listed as containing the whole Bible; it is universally agreed that the 1475 reference is to this manuscript.

Contents

B originally contained the entire Old and New Testaments, except that it never included the books of Maccabees or the Prayer of Manasseh. The manuscript now has slight defects; in the Old Testament, it omits most of Genesis (to 46:28) and portions of Psalms (lacking Psalms 105-137). In the New Testament, it is defective from Hebrews 9:14 onward (ending ΚΑΤΑ), omitting the end of Hebrews, 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon, and the Apocalypse. It is possible that additional books might have been included at the end -- although it is also possible that the Apocalypse was not included. Indeed, it is barely possible (though this is rarely mentioned) that B originally omitted the Pastorals; this would accord with the contents of its relative 𝔓46.

Date/Scribe

Early estimates of the date of this manuscript, at a time when knowledge of paleography was limited, varied significantly -- e.g. Montfaucon suggested the fifth or sixth century, and Dupin the seventh. But Hug (who was the first to really stress the importance of this manuscript) suggested the fourth century, and this is no longer questioned; B is now universally conceded to belong to the fourth century, probably to the early part of the century. It is in many ways very primitive, having very short book titles and lacking the Eusebian apparatus. It has its own unique system of chapter identifications; that in the gospels is found elsewhere only in Ξ. It uses a continuous system of numbers in Paul, showing that (in one or another of its ancestors), Hebrews stood between Galatians and Ephesians, even though Hebrews stands after Thessalonians in B itself. There is a second system in Paul as well; we also find two sets of chapter numbers in Acts and the Catholic Epistles, save that 2 Peter is not numbered (perhaps because it was not considered canonical by the unknown person who created this chapter system). This system is also found, in part, in ℵ; Ropes considers it slightly corrupt.

A single scribe seems to have been responsible for almost all of the New Testament, though two scribes worked on the Old. (There is some dispute about this; some see four scribes, and some argue that the the scribe who wrote Psalms 79 to the end of the Old Testament also wrote Matthew 1:1-9:5; the scribe of the rest of the New Testament is sometimes said to have written the middle part of the Old Testament, from 1 Samuel 19 to Psalm 78.)

There were two primary correctors, though the dates of both are rather uncertain. The first is tentatively dated to the sixth century; the second comes from the tenth or eleventh. The second of these is much the more important, though more for damage done than for the actual readings supplied. The date of this scribe is based mostly on the handful of readings he added -- some of these are in minuscule script. This scribe, finding the manuscript somewhat faded, proceeded to re-ink the entire text (except for a few passages which he considered inauthentic). This scribe also added accents and breathings.

This re-inking had several side effects, all of them (from our standpoint) bad. First, it defaced the appearance of the letters, making it much harder to do paleographic work. Second, it rendered some of the readings of the original text impossible to reconstruct. And third (though related to the preceding), it makes it very difficult to tell if there are any original accents, breathings, punctuation, etc. Such marks will generally disappear under the re-inking. Only when such a mark has not been re-inked can we be sure it came from the original hand. Modern techniques could perhaps see through the work of this defacer, but as far as I know, no one has been willing to put up the money for this, and I doubt the Vatican would allow the manuscript to leave their library for as long as the project would need.

It is not absolutely certain when B was damaged, but it certainly happened in the manuscript era, because a supplement with the missing material was later added to the volume. This supplement is late, in a minuscule hand (manuscript 1957, dated paleographically to the fifteenth century; it is believed that the Apocalypse was copied from a manuscript belonging to Cardinal Bessarion. It has been conjectured that Bessarion contributed B to the Vatican library, but this is pure conjecture; all that is known is that the manuscript has been in the library since the compiling of the first catalog in 1475. Ropes thinks it most unlikely that Bessarion would have parted with it.)

Most think the manuscript originated in Egypt, perhaps in Alexandria. Ropes goes so far as to conjecture that it was taken from Egypt to Sicily in the aftermath of the Arab conquest of Egypt, then taken from there to Calabria.

Many have attempted to connect the manuscript to Athanasius, typically based on the books it includes. Some are quite adamant: Since it includes the books Athanasius approved, it must be based on his list. There are a number of objections to this, none of them fatal but all of them quite significant. First and foremost, it is quite possible that B predates Athanasius's career. Second, although the books in B are all in Athanasius's list of accepted books, by the time B was written, the canon was pretty well fixed; only a handful of books were still in doubt. The only really doubtful books included in B are 2 and 3 John and Jude. We do not know that B included the Apocalypse (there is no evidence either way), and we do not know that it included only the 26 or 27 approved books of the New Testament; it could have included other books such as I Clement. And, indeed, it's just possible that, like 𝔓46, it omitted the Pastorals. Yes, it is likely that B had the same canon as Athanasius, but it is beyond proof.

Tischendorf was of the opinion that the scribe who wrote the New Testament of B was also his scribe "D" of ℵ. But it should be kept in mind that Tischendorf never actually got to compare the two. This suggestion is now rejected -- and, as Ropes pointed out, any inferences made on the basis that the two were the same must also be set aside.

Description and Text-type

This is the manuscript. The big one. The key. It is believed that every non-Byzantine edition since Westcott and Hort has been closer to B than to any other manuscript. There is general consensus about the nature of its text: Westcott and Hort called it "Neutral" (i.e. Alexandrian); Von Soden listed it as H (Alexandrian), Wisse calls it Group B (Alexandrian), the Alands place it in Category I (which in practice also means Alexandrian). No other substantial witness is as clearly a member of this text-type; B very nearly defines the Alexandrian text.

Despite the unanimity of scholars, the situation is somewhat more complicated than is implied by the statement "B is Alexandrian." The facts change from corpus to corpus.

In the Gospels, Westcott and Hort centered the "Neutral"/Alexandrian text around B and ℵ (01). At that time, they agreed more closely with each other than with anything else (except that Z had a special kinship with ℵ). Since that time, things have grown more complex. B has been shown to have a special affinity with 𝔓75 -- an affinity much greater than its affinity with ℵ, and of a different kind. The scribal problems of 𝔓66 make it harder to analyse (particularly since ℵ departs the Alexandrian text in the early chapters of John), but it also appears closer to B than ℵ. Among later manuscripts, L has suffered much Byzantine mixture, but its non-Byzantine readings stand closer to B than to ℵ. Thus it appears that we must split the Alexandrian text of the Gospels into, at the very least, two subfamilies, a B family (𝔓66, 𝔓75, B, L, probably the Sahidic Coptic) and an ℵ family (ℵ, Z, at least some of the semi-Alexandrian minuscules). This is a matter which probably deserves greater attention.

There is little to be said regarding Acts. B seems once again to be the purest Alexandrian manuscript, but I know of no study yet published which fully details the relations between the Alexandrian witnesses. It is likely that B, A, and ℵ all belong to the same text-type. We have not the data to say whether there are sub-text-types of this text.

In Paul, the matter is certainly much more complex. Hort described B, in that corpus, as being primarily Alexandrian but with "Western" elements. This was accepted for a long time, but has two fundamental flaws. First, B has many significant readings not found in either the Alexandrian (ℵ A C 33 etc.) or the "Western" (D F G latt) witnesses. Several good examples of this come from Colossians: In 2:2, B (alone of Greek witnesses known to Hort; now supported by 𝔓46 and implicitly by the members of Family 1739) has του θεου Χριστου; in 3:6, B (now supported by 𝔓46) omits επι τους υιους της απειθειας Also, B was the earliest witness known to Hort; was it proper to define its text in terms of two text-types (Western and Alexandrian) which existed only in later manuscripts?

It was not until 1946 that G. Zuntz examined this question directly; the results were published in 1953 as The Text of the Epistles: A Disquisition Upon the Corpus Paulinum. Zuntz's methods were excessively laborious, and cannot possibly be generalized to the entire tradition -- but he showed unquestionably that, first, B and 𝔓46 had a special kinship, and second, that these manuscripts were not part of the mainstream Alexandrian text. This was a major breakthrough in two respects: It marked the first attempt to distinguish the textual history of the Epistles from the textual history of the Gospels (even though there is no genuine reason to think they are similar), and it also marked the first attempt, in Paul, to break out of Griesbach's Alexandrian/Byzantine/Western model.

Zuntz called his proposed fourth text-type "proto-Alexandrian" (p. 156), and lists as its members 𝔓46 B 1739 (plus the relatives of the latter; Zuntz was aware of 6 424** M/0121 1908; to this now add 0243 1881 630 2200) sa bo Clement Origen.

It appears to me that even this classification is too simple; there are five text-types in Paul -- not just the traditional Alexandrian, Byzantine, and "Western" texts, but two others which Zuntz combined as the "Proto-Alexandrian" text. (This confusion is largely the result of Zuntz's method; since he worked basically from 𝔓46, he observed the similarities of these manuscripts to 𝔓46 but did not really analyse the places where they differ.) The Alexandrian, "Western," and Byzantine texts remain as he found them. From the "Proto-Alexandrian" witnesses, however, we must deduct Family 1739, which appears to be its own type. Family 1739 does share a number of readings with 𝔓46 and B, but it also shares special readings with the Alexandrian and "Western" texts and has a handful of readings of its own. It also appears to me that the Bohairic Coptic, which Zuntz called Alexandrian, is actually closer to the true Alexandrian text.

This leaves B with only two full-fledged allies in Paul: 𝔓46 and the Sahidic Coptic. I also think that Zuntz's title "Proto-Alexandrian" is deceptive, since the 𝔓46/B type and the Alexandrian text clearly split before the time of 𝔓46. As a result, I prefer the neutral title 𝔓46/B type (if we ever find additional substantial witnesses, we may be able to come up with a better name).

When we turn to the Catholics, the situation seems once again to be simple. Most observers have regarded B as, once again, the best of the Alexandrian witnesses -- so, e.g., Richards, who in the Johannine Epistles places it in the A2 group, which consists mostly of the Old Uncials: ℵ A B C Ψ 6.

There are several peculiar points about these results, though. First, Richards lumps together three groups as the "Alexandrian text." Broadly speaking, these groups may be described as Family 2138 (A1), the Old Uncials (A2), and Family 1739 (A3). And, no matter what one's opinion about Family 1739, no reasonable argument can make Family 2138 an Alexandrian group. What does this say about Richards's other groups?

Another oddity is the percentages of agreement. For the A2 group, Richards gives these figures for rates of agreement with the group profile (W. L. Richards, The Classification of the Greek Manuscripts of the Johannine Epistles, SBL Dissertation Series, 1977, p. 141):

| Manuscript | Agreement % |

| Ψ | 96% |

| C | 94% |

| ℵ | 94% |

| B | 89% |

| A | 81% |

| 6 | 72% |

This is disturbing in a number of ways. First, what is 6 doing in the group? It's far weaker than the rest of the manuscripts. Merely having a 70% agreement is not enough -- not when the group profiles are in doubt! Second, can Ψ, which has clearly suffered Byzantine mixture, really be considered the leading witness of the type? Third, can C (which was found by Amphoux to be associated with Family 1739 in the Catholics) really be the leading Old Uncial of this type? Fourth, it can be shown that most of the important Alexandrian minuscules (e.g. 33, 81, 436, none of which were examined by Richards) are closer to A than to B or ℵ. Ought not A be the defining manuscript of the type? Yet it agrees with the profile only 81% of the time!

A much more reasonable approach is to take more of the Alexandrian minuscules into account, and a rather different picture emerges. Rather than being the weakest Alexandrian uncial, A becomes (in my researches) the earliest and key witness of the true Alexandrian type, heading the group A Ψ 33 81 436 al. The clear majority of the Alexandrian witnesses in the Catholics go here, either purely (as in the case, e.g., of 33) or with Byzantine mixture (as, e.g., in 436 and its near relative 1067). In this system, both B and ℵ stand rather off to the side -- perhaps part of the same type, but not direct ancestors of anything. We might also note that B has a special kinship, at least in the Petrine epistles, with 𝔓72, the one substantial papyrus of the Catholic Epistles. Despite Richards, it appears that B and 𝔓72 form at least a sub-type of the Alexandrian text.

One thing that's worth keeping in mind as we assess B in the New Testament: Although B is generally considered the best manuscript of the Septuagint also, being frequently the best witness to the "Old Greek," there are exceptions -- places where it is kaige or mixed, such as parts of Kings and the Psalter. This does not tell us anything about the New Testament text, of course, but it is a reminder that B's text had to be assembled from multiple sources, just like every other manuscript. Most of those sources are old, but doesn't mean they are all the same.

Other Symbols Used for this Manuscript

von Soden: δ1

Bibliography

Note: As with all the major uncials, no attempt is made to compile a complete bibliography.

Collations:

B has been published several times, including several recent photographic editions (the earliest from 1904-1907; full colour editions were published starting in 1968). It is important to note that the early non-photographic editions are not reliable. Tischendorf, of course, listed the readings of the manuscript, but this was based on a most cursory examination; the Vatican authorities went to extraordinary lengths to keep him from examining Vaticanus. Others who wished to study it, such as Tregelles, were denied even the right to see it. The first edition to be based on actual complete examination of the manuscript was done by Cardinal Mai (4 volumes; a 1 volume edition came later) -- but this was one of the most incompetently executed editions of all time. Not only is the number of errors extraordinarily high, but no attention is paid to readings of the first hand versus correctors, and there is no detailed examination of the manuscript's characteristics. Despite its advantages, it is actually less reliable than Tischendorf, and of course far inferior to recent editions. Philipp Buttmann produced a New Testament edition based largely on B, but he had B's text via Mai, which he seemingly didn't trust very much, so the resulting edition isn't much like B or anything else (except 2427, which apparently was copied from Buttmann).

Sample Plates:

Images are found in nearly every book on NT criticism which contains pictures.

Editions which cite:

Cited in all editions since Tischendorf

Other Works:

The bibliography for B is too large and varied to be covered here. The reader

is particularly referred to a work already mentioned:

G Zuntz, The Text of the Epistles: A Disquisition Upon the Corpus Paulinum.

See also, e.g., S. Kubo, 𝔓72 and the Codex Vaticanus.

Manuscript C (04)

Location/Catalog Number

Paris, National Library Greek 9.

Contents

C originally contained the entire Old and New Testaments, but was erased in the twelfth century and overwritten with Syriac works of Ephraem. The first to more or less completely read the manuscript was Tischendorf, but it is likely that it will never be fully deciphered (for example, the first lines of every book were written in red or some other colour of ink, and have completely vanished). In addition, very many leaves were lost when the book was rewritten; while it is barely possible that some may yet be rediscovered, there is no serious hope of recovering the whole book.

As it now stands, C lacks the following New Testament verses in their entirety:

- Matt. 1:1-2, 5:15-7:5, 17:26-18:28, 22:21-23:17, 24:10-45, 25:30-26:22, 27:11-46, 28:15-end

- Mark 1:1-17, 6:32-8:5, 12:30-13:19

- Luke 1:1-2, 2:5-42, 3:21-4:5, 6:4-36, 7:17-8:28, 12:4-19:42, 20:28-21:20, 22:19-23:25, 24:7-45

- John 1:1-3, 1:41-3:33, 5:17-6:38, 7:3-8:34 (does not have space for 7:53-8:11), 9:11-11:7, 11:47-13:8, 14:8-16:21, 18:36-20:25

- Acts 1:1-2, 4:3-5:34, 6:8, 10:43-13:1, 16:37-20:10, 21:31-22:20, 23:18-24:15, 26:19-27:16, 28:5-end

- Romans 1:1-2, 2:5-3:21, 9:6-10:15, 11:31-13:10

- 1 Corinthians 1:1-2, 7:18-9:16, 13:8-15:40

- 2 Corinthians 1:1-2, 10:8-end

- Galatians 1:1-20

- Ephesians 1:1-2:18, 4:17-end

- Philippians 1:1-22, 3:5-end

- Colossians 1:1-2

- 1 Thessalonians 1:1, 2:9-end

- 2 Thessalonians (entire book)

- 1 Timothy 1:1-3:9, 5:20-end

- 2 Timothy 1:1-2

- Titus 1:1-2

- Philemon 1-2

- Hebrews 1:1-2:4, 7:26-9:15, 10:24-12:15

- James 1:1-2, 4:2-end

- 1 Peter 1:1-2, 4:5-end

- 2 Peter 1:1

- 1 John 1:1-2, 4:3-end

- 2 John (entire book)

- 3 John 1-2

- Jude 1-2

- Revelation 1:1-2, 3:20-5:14, 7:14-17, 8:5-9:16, 10:10-11:3, 16:13-18:2, 19:5-end

(and, of course, C may be illegible even on the pages which survive). We might note that we are fortunate to have even this much of the New Testament; we have significantly more than half of the NT, but much less than half of the Old Testament.

Date/Scribe

The original writing of C is dated paleographically to the fifth century, and is quite fine and clear (fortunately, given what has happened to the manuscript since). The scribes of the Old and New Testament are thought to be different; some have suggested that a third scribe wrote Acts. Before being erased, it was worked over by two significant correctors, C2 (Cb) and C3 (Cc). (The corrector C1 was the original corrector, but made very few changes. C1 is not once cited in NA27.) Corrector C2 is thought to have worked in the sixth century or thereabouts; C3 performed his task around the ninth century. (For more information about the correctors of C, see the article on Correctors.)

It was probably in the twelfth century that the manuscript was erased and overwritten; the upper writing is a Greek translation of 38 Syriac sermons by Ephraem.

The manuscript's history has been traced back to the early sixteenth century, when it was in the possession of the Florentine Cardinal Ridolfi (died 1550). There is no evidence of how it was taken from the East to Italy.

Description and Text-type

It is usually stated that C is a mixed manuscript, or an Alexandrian manuscript with much Byzantine mixture. The Alands, for instance, list it as Category II; given their classification scheme, that amounts to a statement that it is Alexandrian with Byzantine influence. Von Soden lists it among the H (Alexandrian) witnesses, but not as a leading witness of the type.

The actual situation is much more complex than that, as even the Alands' own figures reveal (they show a manuscript with a far higher percentage of Byzantine readings in the gospels than elsewhere). The above description is broadly accurate in the Gospels; it is not true at all elsewhere.

In the Gospels, the Alands' figures show a manuscript which is slightly more Byzantine than not, while Wisse lists C as mixed in his three chapters of Luke. But these are overall assessments; a detailed examination shows C to waver significantly in its adherence to the Alexandrian and Byzantine texts. While at no point entirely pure, it will in some sections be primarily Alexandrian, in others mostly Byzantine.

Gerben Kollenstaart brings to my attention the work of Mark R. Dunn in An Examination of the Textual Character of Codex Ephraemi Syri Rescriptus (C, 04) in the Four Gospels (unpublished Dissertation, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary 1990). Neither of us has seen this document, but we find the summary, "C is a weak Byzantine witness in Matthew, a weak Alexandrian in Mark, and a strong Alexandrian in John. In Luke C's textual relationships are unclear" (Summarized in Brooks, The New Testament Text of Gregory of Nyssa, p. 60, footnote 1). I dislike the terminology used, as it looks much too formulaic and appears to assume that C's textual affinities change precisely at the boundaries between books. (Given C's fragmentary state, this is even more unprovable than usual.) But the general conclusion seems fair enough: Matthew is the most Byzantine, John the least. In all cases, however, one suspects Byzantine and Alexandrian mixture -- probably of Byzantine readings atop an Alexandrian base. This would explain the larger number of Byzantine readings in Matthew: As is often the case, the corrector was most diligent at the beginning.

Outside the Gospels, C seems to show the same sort of shift shown by its near-contemporary, A -- though, because C possessed Alexandrian elements in the gospels, the shift is less noticeable. But it is not unfair to say that C is mixed in the Gospels and almost purely non-Byzantine elsewhere.

In short works such as Acts and the Catholic Epistles, the limited amount of text available makes precise determinations difficult. In the Acts, we can at least state definitively that C is less Byzantine than it is in the Gospels, but any conclusion beyond that is somewhat tentative. The usual statement is that C is Alexandrian, and I know of no counter-evidence. Nonetheless, given the situation in the Catholic Epistles, I believe this statement must be taken with caution.

The situation in the Catholic Epistles is purely and simply confused. The published evaluations do not agree. W. L. Richards, in his dissertation on the Johannine Epistles using the Claremont Profile Method, does a fine job of muddling the issue. He lists C as a member of the A2 text, which appears to be the mainstream Alexandrian text (it also contains ℵ, A, and B). But something funny happens when one examines C's affinities. C has a 74% agreement with A, and a 77% agreement with B, but also a 73% agreement with 1739, and a 72% agreement with 1243. This is hardly a large enough difference to classify C with the Alexandrians as against the members of Family 1739. And, indeed, Amphoux and Outtier link C with Family 1739, considering their common material possibly "Cæsarean."

My personal results seem to split the difference. If one assumes C is Alexandrian, it can be made to look Alexandrian. But if one starts with no such assumptions, then it appears that C does incline toward Family 1739. It is not a pure member of the family, in the sense that (say) 323 is; 323, after all, may be suspected of being descended (with mixture) from 1739 itself. But C must be suspected of belonging to the type from which the later Family 1739 descended. (Presumably the surviving witnesses of Family 1739 are descended from a common ancestor more recent than C, i.e. Family 1739 is a sub-text-type of the broader C/1241/1739 type.) It is possible (perhaps even likely) that C has some Alexandrian mixture, but proving this (given the very limited amount of text available) will require a very detailed examination of C.

Westcott, in his commentary on the Johannine Epistles, lists the peculiar readings of C (that is, those not shared by ℵ A B), adding that they "have no appearance of genuiness":

- 1 Jn 1:3 omit δε with the late mss. [C* P 33 81 322 323 429 453 630 945 1241 1505 1739 2298 hark sa arm]

- 1 Jn 1:4 add εν ημιν [C* pesh]

- 1 Jn 1:5 επαγγελια with the late mss. [C P 33 69 81 181 323 429 436 614 630 945 1505 1739 2298 hark bo (ℵ2 Ψ αγαπη της επαγγελιας)]

- 1 Jn 1:9 omit ημας [C singular reading]

- 1 Jn 2:4 omit οτι with the late mss. [C K L P 049 69 1881 arm; not 1739]

- 1 Jn 2:21 omit παν [singular reading]

- 1 Jn 3:14 add τον αδελφον with the late mss. [C K L Ψ 81 (P 69 206 614 630 1505 τον αδελφον αυτου)]

- 1 Jn 3:20 κυριος for θεος [singular reading]

- 1 Jn 4:2 χριστον ιησουν [singular reading]

Westcott's statement seems to be generally true -- all the items here appear to be either singular, simple errors of omission, or minor paraphrases. But C still appears highly valuable when in company with good witnesses.

In Paul, the situation is simpler: C is a very good witness, of the Alexandrian type as found in ℵ A 33 81 1175 etc. (This as opposed to the type(s) found in 𝔓46 or B or 1739). So far as I know, this has never been disputed.

In the Apocalypse, C is linked with A in what is usually called the Alexandrian text. No matter what it is called, this type (which also includes the Vulgate and most of the better minuscules) is considered the best type. Note that this is not the sort of text found in 𝔓47 and ℵ.

Other Symbols Used for this Manuscript

von Soden: δ3

Bibliography

Note: As with all the major uncials, no attempt is made to compile a complete bibliography.

Collations:

Various editors extracted occasional readings from the manuscript, but Tischendorf was the first to read C completely. Tischendorf is often reported to have used chemicals, but in fact it is believed that they were applied before his time -- and they have hastened the decay of the manuscript. Tischendorf, working by eye alone, naturally did a less than perfect job. Robert W. Lyon, in 1958-1959, published a series of corrections in New Testament Studies (v). But this, too, is reported to be imperfect. The best current source is the information published in the Das Neue Testament auf Papyrus series. But there is no single source which fully describes C.

Sample Plates:

Sir Frederick Kenyon & A. W. Adams, Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts

Editions which cite:

Cited in all editions since Tischendorf

Other Works:

Mark R. Dunn, An Examination of the Textual Character of Codex Ephraemi Syri Rescriptus (C, 04)

in the Four Gospels (unpublished Dissertation, Southwestern Baptist Theological

Seminary 1990)

Manuscript Dea (05)

Location/Catalog Number

Cambridge, University Library Nn. 2. 41. The well-known Codex Bezae, so-called because it was once the possession of Theodore Beza.

Contents

Greek/Latin diglot, with the Greek on the left page. The Greek currently contains the Gospels and Acts with lacunae; the manuscript lacks Matt. 1:1-20, 6:20-9:20, 27:2-12, John 1:16-3:26, Acts 8:29-10:14, 21:2-10, 16-18, 22:10-20, 29-end. In addition, Matt. 3:7-16, Mark 16:15-end, John 18:14-20:13 (a total of ten leaves) are supplements from a later hand (estimated to date from the tenth to twelfth century). The Gospels are in the "Western" order Matthew, John, Luke, Mark, though Chapman offered evidence that an ancestor had the books in the order Matthew, Mark, John, Luke.

Since the Greek and Latin are on facing pages, the losses to the Latin side are not precisely parallel; d (the symbol for the Latin of D; Beuron #5) lacks Matt. 1:1-11, 2:20-3:7, 6:8-8:27, 26:65-27:2, Mark 16:6-20, John 1:1-3:16, 18:2-20:1, Acts 8:21-10:3, 20:32-21:1, 21:8-9, 22:3-9, 22:21-end. In addition, the Latin includes 3 John 11-15.

The original contents of D are somewhat controversial. Obviously it must have contained the Gospels, Acts, and 3 John. This would seem to imply that the manuscript originally contained the Gospels, Catholic Epistles, and Acts (in that order). This, however, does not fit well with the pagination of the manuscript; Chapman theorized that the manuscript actually originally contained the Gospels, Apocalypse, 1 John, 2 John, 3 John, and Acts (in that order), and others (e.g. Ropes) have accepted the hypothesis. This makes sense, but cannot be considered certain -- particularly since it is at least possible that some works would have been included in only one language (e.g. the Catholic Epistles in Latin only, plus some other work, also in Latin only). It's even possible that there was a non-canonical work and that it was deliberately excised.

Date/Scribe

The manuscript has been variously dated, generally from the fourth to the sixth centuries (very early examiners gave even more extreme dates: Kipling, who published a facsimile in 1793, claimed a second century date, and Michaelis also considered it the earliest manuscript known, but a few guessed dates as late as the seventh century.) In the middle of the twentieth century, the tendency seemed to be to date it to the sixth century; currently the consensus seems to be swinging back toward the fifth. It is very difficult to achieve certainty, however, as the handwriting is quite unusual. The Greek and Latin are written in parallel sense lines, and the scribe uses a very similar hand for both languages -- so much so that a casual glance cannot tell the one language from the other; one must look at the actual letters and what they spell.

The unusual writing style is only one of the curiosities surrounding the scribe of D. It is not clear whether his native language was Greek or Latin; both sides of the manuscript contain many improbable errors. (Perhaps the easiest explanation is that the scribe's native language was something other than Greek or Latin.)

D's text, as will be discussed below, was far removed from the Byzantine standard (or, perhaps, from any other standard). As a result, it was corrected many times by many different scribes. Scrivener believed that no fewer than nine correctors worked on the manuscript, the first being nearly contemporary with the original scribe and the last working in the eleventh or twelfth century. Some have counted as many as twenty correctors. (Ironically, there is little evidence that the manuscript was corrected when it was written.) In general, these correctors brought the manuscript closer to the Byzantine text (as well as adding occasional marginal comments and even what appear to be magical formulae at the bottom of the pages of Mark). For more recent views on these correctors, see D. C. Parker's work on Codex Bezae; Parker redates some of the correctors (moving them back some centuries), and believes that one had an Alexandrian text. The majority of the correctors were most interested in the Greek text, although one worked mostly on the Latin.

The known history of the manuscript does not clarify the significance its text; it cannot be traced back far enough. We first hear of it at the time of the Council of Trent, when it apparently was consulted about certain Latin readings. The readings printed by Stephanus as β seem to have been taken down at this time. After this it was in the possession of the Monastery of Irenæus at Lyon (where it had probably been before being taken to Trent); it came to Beza from there in 1562, probably as a result of commotion in the town. Beza gave it to Cambridge University in 1582.

There are indications -- though they fall far short of proof -- that the codex had been in Lyon for some time before it was noticed. There are 71 notes in the margin, from a later hand than the original text but probably no later than the tenth century, that seem to have been intended for fortune-telling. These are similar to a series found in the Latin Codex Sangermanensis, also associate with Lyon. And Quentin thought that the martyrology of Ado of Lyon had certain Biblical readings associated with the Bezan text. Given that Quentin found only seven such readings, the association is suggestive but certainly not conclusive. But it might explain why the long line of Greek correctors eventually stopped working on the manuscript: there were no Greek scholars in Lyon. This would, however, hint that the manuscript originated elsewhere. This is supported by the fact that the manuscript contains indications for the Byzantine lectionary, which was not used in Lyon. Many have argued for southern Italy, but Ropes counters by saying that there were no Greek communities in southern Italy at the time Bezae was written. He prefers Sicily, which was far more Greek. I don't think this compelling; even a Latin-speaking community might have people who wanted to look at the Greek original -- and who would like a parallel version. I incline to agree with those who say the best bet for the origin is southern Italy, but honesty compels us to admit that we really don't know.

Based on multiple indications including the loss of whole lines from both the Greek and the Latin, it is believed that Bezae was copied from original that was already in bilingual sense lines (so there was evidently a specially-compiled bilingual edition of which it was a copy), but that Bezae does not follow the pagination of this original, just the lineation.

Description and Text-type

The text of D can only be described as mysterious. We don't have answers about it; we have questions. There is nothing like it in the rest of the New Testament tradition. It is, by far the earliest Greek manuscript to contain John 7:53-8:11 (though it has a form of the text quite different from that found in most Byzantine witnesses). It is the only Greek manuscript to contain (or rather, to omit) the so-called Western Non-Interpolations. In Luke 3, rather than the Lucan genealogy of Jesus, it has an inverted form of Matthew's genealogy (this is unique among Greek manuscripts). In Luke 6:5 it has a unique reading about a man working on the Sabbath. D and Φ are the only Greek manuscripts to insert a loose paraphrase of Luke 14:8-10 after Matt. 20:28. And the list could easily be multiplied; while these are among the most noteworthy of the manuscript's readings, it has a rich supply of other singular variants.

In the Acts, if anything, the manuscript is even more extreme than in the Gospels. F. G. Kenyon, in The Western Text of the Gospels and Acts, describes a comparison of the text of Westcott & Hort with that of A. C. Clark. The former is essentially the text of B, the latter approximates the text of D so far as it is extant. Kenyon lists the WH text of Acts at 18,401 words, that of Clark at 19,983 words; this makes Clark's text 8.6 percent longer -- and implies that, if D were complete, the Bezan text of Acts might well be 10% longer than the Alexandrian, and 7% to 8% longer than the Byzantine text.

This leaves us with two initial questions: What is this text, and how much authority does it have?

Matthaei referred to it as editio scurrilis, but nineteenth century scholars inclined to give the text great weight. Yes, D was unique, but in that era, with the number of known manuscripts relatively small, that objection must have seemed less important. D was made the core witness -- indeed, the key and only Greek witness -- of what was called the "Western" text.

More recently, Von Soden listed D as the first and chief witness of his Iα text; the other witnesses he includes in the type are generally those identified by Streeter as "Cæsarean" (Θ 28 565 700 etc.) The Alands list it as Category IV -- a fascinating classification, as D is the only substantial witness of the type. Wisse listed it as a divergent manuscript of Group B -- but this says more about the Claremont Profile Method than about D; the CPM is designed to split Byzantine strands, and given a sufficiently non-Byzantine manuscript, it is helpless. (Biologists have a term for this phenomenon: It's known as "long branch assimiliation." If you have a large mass of closely related entities, and two entities not related to the large mass, the two distant entities may look related just because they are way out in the middle of nowhere.)

The problem is, Bezae remains unique among Greek witnesses. Yes, there is a clear "Western" family in Paul (D F G 629 and the Latin versions.) But this cannot be identified with certainty with the Bezan text; there is no "missing link" to prove the identity. Not one Greek manuscript contains a "Western" text of both the Gospels and Paul! There are Greek witnesses which have some kinship with Bezae -- ℵ in the early chapters of John; the fragmentary papyri 𝔓29 and 𝔓38 and 𝔓48 in Acts. But none of these witnesses is complete, and none is as extreme as Bezae.

D's closest kinship is with the Latin versions, but none of them are as extreme as it is. D is, for instance, the only manuscript to substitute Matthew's genealogy of Jesus for Luke's. On the face of it, this is not a "Western" reading; it is simply a Bezan reading.

Then there is the problem of D and d. The one witness to consistently agree with Dgreek is its Latin side, d. Like D, it uses Matthew's genealogy in Luke. It has (that is, it omits) all the "Western Non-Interpolations." And, perhaps most notably, it has a number of readings which appear to be assimilations to the Greek.

Yet so, too, does D seem to have assimilations to the Latin. Many of them.

We are almost forced to the conclusion that D and d have, to some extent, been conformed to each other. The great question is, to what extent, and what did the respective Greek and Latin texts look like before this work was done?

On this point there can be no clear conclusion. Wettstein theorized that the Greek text was conformed to the Latin. Matthaei had a modified version of this in which the marginal readings of a commentary manuscript might also have been involved, and considered it deliberately edited. Hort thought that D arose more or less naturally; while he considered its text bad, he was willing to allow it special value at some points where its text is shorter than the Alexandrian. (This is the whole point of the "Western Non-Interpolations.") More recently, however, Aland has argued that D is the result of deliberate editorial work. This is unquestionably true in at least one place: The Lukan genealogy of Jesus. Is it true elsewhere? This is the great question, and one for which there is still no answer.

As noted, Bezae's closest relatives are Latin witnesses. And these exist in abundance. If we assume that these correspond to an actual Greek text-type, then Bezae is clearly a witness to this type. And we do have evidence of a Greek type corresponding to the Latins, in Paul. The witnesses D F G indicate the existence of a "Western" type. So Bezae does seem to be a witness of an actual type, both in the Gospels (where its text is relatively conservative) and in the Acts (where it is far more extravagant). (This is in opposition to the Alands, who have tended to deny the existence of the "Western" text.)

So the final question is, is Bezae a proper witness to this text which underlies the Latin versions? Here it seems to me the correct answer is probably no. To this extent, the Alands are right. Bezae has too many singular readings, too many variants which are not found in a plurality of the Latin witnesses. It probably has been edited (at least in Luke and Acts; this is where the most extreme readings occur). If this is true (and it must be admitted that the question is still open), then it has important logical consequences: It means that the Greek text of Bezae (with all its assimilations to the Latin) is not reliable as a source of readings. If D has a reading not supported by another Greek witness, the possibility cannot be excluded that it is an assimilation to the Latin, or the result of editorial work.

All that being said, there remains disagreement on just how heavily edited, just how wild, just how peculiar the text of D is. And, one suspects, that will remain true until and unless another similar Greek text shows up.

Other Symbols Used for this Manuscript

von Soden: δ5

Bibliography

Note: As with all the major uncials, no attempt is made to compile a complete bibliography.

Collations:

The standard reference is probably still F. H. A. Scrivener, Bezae Codex Canatabrigiensis, simply because of Scrivener's detailed and careful analysis. J. Rendel Harris published a photographic reproduction in 1899. See also J. H. Ropes, The Text of Acts and A. C. Clark, The Acts of the Apostles, both of which devote considerable attention to the text of Bezae in Acts.

Sample Plates:

(Sample plates in almost all manuals of NT criticism)

Editions which cite:

Cited in all editions since Tischendorf, and most prior to that.

Other Works:

The most useful work is probably James D. Yoder's Concordance to the

Distinctive Greek Text of Codex Bezae. There are dozens of specialized

studies of one or another aspect of the codex, though few firm conclusions

can be reached (perhaps the most significant is the conclusion of Holmes

and others that Bezae has been more thoroughly reworked in Luke than in

Matthew or Mark). See also the recent work by D. C. Parker, Codex

Bezae.

Manuscript Dp (06)

Location/Catalog Number

Paris, National Library Greek 107, 107 AB. The famous Codex Claromontanus -- so-called because Beza reported that it had been found at Clermont. It should not be confused with the even more famous, or infamous, Codex Bezae, also designated D.

Contents

Greek/Latin diglot, with the Greek and Latin in stichometric lines on facing pages. Contains the Pauline Epistles with the slightest of lacunae: It lacks Romans 1:1-7 (though we can gain some information about the readings of D in these verses from Dabs). In addition, Romans 1:27-30 and 1 Corinthians 14:13-22 are supplements from a later hand. (Scrivener, however, notes that this hand is still "very old.") Hebrews is placed after Philemon.

The Latin side, known as d (Beuron 75) has not been supplemented in the same way as the Greek; it lacks 1 Corinthians 14:9-17, Hebrews 13:22-end. Romans 1:24-27 does come from a supplement.

Scrivener observes that the very fine vellum actually renders the manuscript rather difficult to read, as the writing on the other side often shows through. The extent of this problem varies from page to page, but often the ink from the reverse side is almost as visible as that on the side being read. This is a problem even with the photographs on the Paris Library web site. Also, the scribe apparently had rather poor pen technique; the darkness of the ink varies from letter to letter. The problem is made worse by the fact that, on many pages, the ink has flaked off. It is not a very easy manuscript to read; the online scans are often barely legible.

Date/Scribe

The first three lines of each book is written in red ink. The original ink is brown, sometimes dark, sometimes light; some of the correctors used much blacker ink. Greek and Latin hands are similar looking and elegant in a simple way.

Almost all scholars have dated D to the sixth century (some specifying the second half of that century); a few very early examiners would argued for the seventh century. The writing is simple, without accents or breathings; some of the uncial forms seem to be archaic. The Greek is more accurately written than the Latin; the scribe's first language was probably Greek. We should note certain broad classes of errors, however. The scribe very frequently confuses the verb ending -θε with -θαι; this occurs so regularly that we can only say that D is not a witness at variants of this sort.

A total of nine correctors have been detected, though not all of these are important. The first important corrector (D** or, in NA26, D1) dates probably from the seventh century; the single most active corrector (D*** or D2, who added accents and breathings and made roughly 2000 changes in the text) worked in the ninth or tenth century; the final significant corrector (D*** or Dc) probably dates from the twelfth century or later.

The corrections to the Greek side are much more numerous than those on the Latin side, which has only minimal corrections.

Description and Text-type

There is an inherent tendency, because D is a Greek/Latin diglot and because it is called "D," to equate its text with the text of Codex Bezae, making them both "Western." This is, however, an unwarranted assumption; it must be proved rather than simply asserted.

There is at least one clear and fundamental difference between Bezae and Claromontanus: They have very different relationships to their parallel Latin texts. The Greek and Latin of Bezae have been harmonized; they are very nearly the same text. The same is not true of Claromontanus. It is true that D and d have similar sorts of text -- but they have not been entirely conformed to each other. The most likely explanation is that dp was translated from a Greek text similar to Dp, and the two simply placed side by side.

Claromontanus also differs from Bezae in that there are Greek manuscripts similar to the former: The close relatives Fp and Gp are also akin, more distantly, to Claromontanus. All three of these manuscripts, it should be noted, have parallel Latin versions (in the case of F, on a facing page; the Latin of G is an interlinear). All three, we might add, are related to the other Old Latin codices (a, b, m; they are rather more distant from r) which do not have Greek parallels.

Thus it seems clear that there is a text-type centred about Dp F G and the Latins. Traditionally this type has been called "Western," and there is no particular reason to change this name.

We should make several points about this Western text of Paul, though. First, it is nowhere near as wild as the text of Codex Bezae, or even the more radical Old Latin witnesses to the Gospels and Acts. Second, it cannot be demonstrated that this is the same type as is found in Bezae. Oh, it is likely enough that Bezae's text is edited from raw materials of the same type as the ancestors of D F G of Paul. But we cannot prove this! Astonishingly enough, there is not one Old Latin witness containing both the Gospels and Paul. There are a few scraps (primarily t) linking the Acts and Paul, but even these are quite minimal. Thus, even if we assume that Bezae and Claromontanus represent the same type, we cannot really describe their relative fidelity to the type (though we can make a very good assumption that Claromontanus is the purer).

We should also examine the relations between the "Western" witnesses in Paul. It is sometimes stated that F and G are descendents of D. This almost certainly not true -- certainly it is functionally untrue; if F and G derive from D, there has been so much intervening mixture that they should be regarded as independent witnesses.

Interestingly, there is a sort of a stylistic difference between D and F/G. F and G appear to have, overall, more differences from the Alexandrian and Byzantine texts, but most of these are small, idiosyncratic readings which are probably the result of minor errors in their immediate exemplars. D has far fewer of these minor variants, but has an equal proportion (perhaps even a higher proportion) of more substantial variants.