Versions of the New Testament

Contents: Introduction * Anglo-Saxon * Arabic * Armenian * Coptic: Sahidic, Bohairic, Other Coptic versions * Ethiopic * Georgian * Gothic * Latin: Old Latin, Vulgate * Old Church Slavonic * Syriac: Diatessaron, Old Syriac, Peshitta, Philoxenian, Harklean, Palestinian, "Karkaphensian" * Udi (Alban, Alvan) * Other Early Versions

Introduction

The New Testament was written in Greek. This was certainly the best language for it to be written in; it was flexible and widely understood.

But not universally understood. In the west, there were many who spoke only Latin. In the east, some spoke only the Syriac/Aramaic dialects. In Egypt the native language was Coptic. And beyond the borders of the Roman Empire there were peoples who spoke even stranger languages -- Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopic, Gothic, Slavonic.

In some areas it was the habit to read the scriptures in Greek whether people understood it or not. But eventually someone had the idea of translating the scriptures into local dialects (we now call these translations "versions"). This was more of an innovation than we realize today; translations of ancient literature were rare. The Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible was one of the very first. Despite the lack of translations in antiquity, it is effectively certain that first Latin versions of the New Testament were in existence by the late second century, and that by the fourth there were also versions in Syriac and several of the Coptic dialects. Versions in Armenian and Georgian followed, and eventually many other languages.

The role of the versions in textual criticism has been much debated. Since they are not in the original language, some people discount them because there are variants they simply cannot convey. But others note, correctly, that these versions convey texts from a very early date. In many instances the text-types they represent survive very poorly or not at all in Greek.

It is true that the versions often have suffered corruption of their own in the centuries since their translation. But such variants usually are of a nature peculiar to the version, and so can be gotten around. When properly used, the versions are one of the best and leading tools of textual criticism. And while they cannot testify to small variant readings, they usually will testify to major differences between texts.

This essay does not attempt to fully spell out the history and limitations of the versions. These points will briefly be touched on, but the emphasis is on the textual nature of the versions. Those who wish to learn more about the history of the versions are advised to consult a reference such as Bruce M. Metzger's The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission, and Limitations (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1977).

In the list which follows, the versions are listed in alphabetical order.

An additional note: Of all the articles in this Encyclopedia, apart from those which touch on science and theology, this has been among the most controversial. I don't mean that people disagree with the results particularly; that happens everywhere, and is if anything more common in the article on the Fathers. But this one seems to make people most upset. Please note that I am not setting out to belittle any particular version, and except in textual matters, I am not expert on these versions. I will stand by the statements on the textual affinities of the more important versions (Latin, Syriac, Coptic; to a lesser extent, the Armenian, Georgian, and Gothic) insofar as they are correctly incorporated into the critical apparatus. For the history and such, I am dependent upon others. If you disagree with the information here, I will try to incorporate suggestions, but there is only so much I can do to make completely contradictory claims fit together....

|

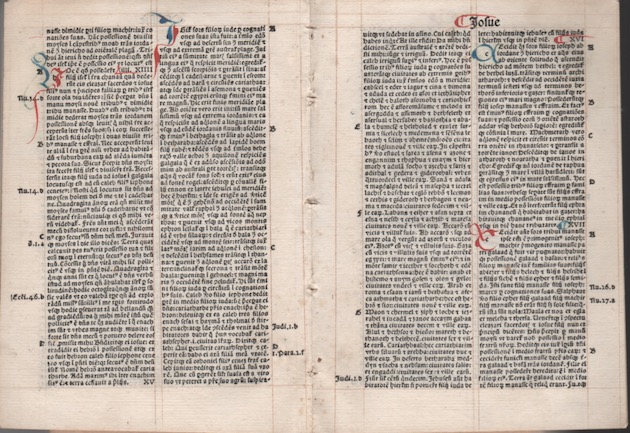

A name used for several translations, made independently and of very different types, used in Britain mostly before the Norman Conquest and of interest more to historians than textual scholars. But since they are important for the understanding of early English literature (they give us, among other things, important vocabulary references), it seems worthwhile to at least mention them here, while understanding that what limited text-critical value they have is mostly for Vulgate criticism (since they were translated from the Latin, not the Greek). | The Lindisfarne Gospels (Wordsworth's Y -- Latin vulgate text with interlinear glosses in the Northumbrian dialect (shown in red highlight). The Latin is from the seventh century; the interlinear is from the tenth. The decorated page containing John 1:1 is shown. |

Although Roman Britain was Christian, the Anglo-Saxon invasions of the late fifth century effectively wiped out Roman Christianity. And it would be centuries before Christianity completely took control of the island, because the German invaders immediately split the island into dozens of small states, of which seven survived to become the "Seven Kingdoms of Britain": Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex, Essex, Sussex, Kent, and East Anglia. To make matters worse, all these kingdoms had slightly different dialects.

It was in 563 that Saint Columba founded the religious center on Iona, bringing Celtic Christianity back to northern Britain. In 596 Pope Gregory the Great sent Augustine to Canterbury to return southern Britain to Christ. The two Christian sects were formally reconciled at the Synod of Whitby in 664. This did not make Britain Christian (and, ironically, it did not bring Ireland into line with Catholic Christianity; that island, now known for its Catholicism, was brought back into line with the Catholic church by the Anglo-Norman invaders who arrived starting in the twelfth century during the reign of Henry II). Still, Whitby at last made the way clear for Christianity to come back to Britain.

The earliest attempts at Anglo-Saxon versions probably date from this early period of conflict with paganism, but they have not survived. Nor has the translation of John made by the Venerable Bede. Alfred the Great worked at a translation, but it seems never to have been completed. All that is known to have existed is a portion of the psalms, including a detailed (though often fanciful) commentary said to have been by Alfred himself. (In this connection it may be worth noting that Asser, Alfred's biographer, at several points quotes the Bible in Old Latin rather than Vulgate forms; even though some very important Vulgate manuscripts come from Britain, the Vulgate was evidently not universally used.)

Our earliest surviving Anglo-Saxon versions date from probably the tenth century. Several of these are continuous text versions; the most famous of these is probably the Hatton Gospels, now in the Bodleian; this beautifully-written manuscript is thought to be from the eleventh century. The most common Old English translation, the so-called West Saxon version, is said to exist in half a dozen copies (of the Gospels), of which British Library I.A.XIV (scans available http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Royal_MS_1_A_XIV&index=0) is perhaps the most noteworthy; another copy is Bodleian Hatton MS. 38; there are hints that these were used into the thirteenth century. Other Old English renderings are interlinear glosses to Latin manuscripts. The interlinears are in several dialects; see the notes on the Lindisfarne Gospels and Rushworth Gospels. The earliest glosses are earlier than the surviving continuous versions; we see Anglo-Saxon glosses in an eighth century British psalter. But, in that case, only a subset of the words are glossed. Glossed psalters were very common, though; they include the famous Vespasian Psalter. One astonishing psalter (Trinity College, Cambridge R.17.1, the Canterbury Psalter or Eadwine Psalter) has all three of the Latin versions of Psalms (the Roman, Gallican, and Hebrew), with an Anglo-Saxon glass to the Roman Psalter and an Anglo-Norman French gloss on the Roman.

Interlinear seem to have been more common than continuous-text Old English versions -- e.g. Andrew C. Kimmens, The Stowe Psalter, lists fourteen different copies of the Latin Psalms with Anglo-Saxon interlinear texts (although some are only partially glossed); one of these, the aforementioned "Vespasian Psalter," is one of the greatest and most beautiful of interlinear manuscripts. (Interestingly, while a dozen of these are in Britain and one ended up in the Morgan Library, one somehow found its way to Paris.) The Psalms, in fact, seem to have been popular for interlinears; Greek/Latin interlinear psalters (usually with the Greek glossing the Latin) are said to have been the most common of all Greek/Latin interlinears, being about as common as all others combined.

In many ways Anglo-Saxon was better suited to literal Bible translation than is modern English, since Anglo-Saxon is an inflected language with greater freedom of word order than modern English. Since, however, all Anglo-Saxon translations are taken from the Latin (unless Bede made some reference to the Greek), they are not generally cited for New Testament textual criticism. This is proper -- though the Saxon versions perhaps deserve more attention for Vulgate criticism; it should be recalled that the early English copies of the Vulgate were of very high value, so the translations could well derive from valuable originals.

Those who wish to see the nature and variation of Old English interlinears might wish to examine the example below. This takes the Vulgate text and shows the interlinears of the Lindisfarne and Rushworth gospels. The Vulgate is as given in Lindisfarne, with variants in Rushworth noted. The sample is from Luke 1.

| Lindisfarne: | forðon | æcsoð | monigo | cunnendo | þoeron | þ̃te geendebrednadon | ðæt gesaga | ðaðe | in | |

| Vulgate: | 11 | Quoniam | quidem | multi | conati | sunt | ordinare | narrationem | quae | in |

| Rushworth: | forðon | æc | monige | cymende | þerun | ðæt giendebredadun | ða gisagune | ðingana ða | in |

| Lindisfarne: | usic | gefylled | aron | ðingana | suæ | gesaldon | us | ðaða | from | fruma | ði | gesegon | 7 | |

| Vulgate: | nobis | completæ | sunt | rerum, | 12 | Sicut | traditerunt | nobis | qui | ab | initio | ipsi | viderunt | et |

| Rushworth: | usih | gifylled | arun | -- | spa | gisaldun | us | ðaðe | from | fruma | ða | gisegun | 7 |

| Lindisfarne: | embehtmenn | þoeron | þordes | gesegen | þæs | æc | me | gefylgde | frõ | frũa | alle | |

| Vulgate: | ministri | fuerunt | sermonis | 13 | Visum | est | et | mihi | assecuto | a | principio | omnia [R: ombibus] |

| Rushworth: | embihtmenn | þerun | þordes | gisegen | þæs | 7 | me | offyligde | from | fruma | alra |

| Lindisfarne: | georne | mið | endebrednyse | ðe | auritta ðu | Theofile | þ̃te | ðu ongette | hior | |

| Vulgate: | diligenter | 14 | Ex | ordine | tibi | optimo [R: obtime | Theophile Theofile] | ut | cognoscas | eorum |

| Rushworth: | georne | mið | endebrednnise | ðe | aprito ðu | Theonphile | ðæt | ðu ongete | hiara |

| Lindisfarne: | þorda | on | ðæm | gelæred | arð | soðfæstnise |

| Vulgate: | verborum | de | quib: | eruditus | es | veritatem |

| Rushworth: | þorda | of | ðæm | gilæred | arð | onsoðfæstnisse |

You don't have to know Old English to see that these two versions are similar but not identical -- an indication probably of regional dialect differences. There was presumably an original gloss which at least one and likely both manuscripts has altered. Or possibly one was partially conformed to the other. In any case, the relationship is complicated.

We should note that the term "Anglo-Saxon" is now frowned upon by linguists, who much prefer the term "Old English." Unfortunately, I have yet to see this term applied to the early English translations. The name "Anglo-Saxon" seems to be used in the same sense that "Ethiopic" is used for a version that is in a language not properly called "Ethiopic": It's a geographic/historical description.

It should be remembered that Old English as a literary language effectively died with the Norman Conquest of 1066; Norman French became the language of commerce and law. Old English works, including Bibles, ceased to be copied.

Three centuries later, English again became the general language of England, and it once again became a literary language. But it had changed utterly, transformed from Old English into Middle English, with a vocabulary much influenced by French and a grammar dramatically simplified. Ordinary people of Chaucer's day could no more understand Old English than they could Greek. When John Wycliff and his followers set out to produce English vernacular Bibles, they seem to have made no reference at all to the Anglo-Saxon versions. They simply went back to the Vulgate and translated it again. (To their credit, they do seem to have tried to compare multiple Vulgate manuscripts. But there is no evidence that the manuscripts they used had any value.)

One should be careful when referring to Wycliff's "version." While it seems likely that he inspired all complete Middle English translations prior to Henry VIII, we know that there were two Wycliffite versions, which in many places are quite different although the Latin underlying them is very similar. Wycliff himself probably worked only on the first, and even that is only partially his (Nicholas of Hereford is believed to have taken at least as large a part, and it is suspected based on translation style that several others were involved as well). The revised version -- which is a much better piece of English prose -- is regarded as primarily the work of John Purvey. Bible translations were eventually banned in England as a result of Wycliff's alleged heresy -- but, curiously, the revised Purvey version seems to have been the more strongly condemned; although it is the more common version, the copies of the Middle English bible owned by royalty (of which there are several) seem to be the earlier Wycliff/Hereford translation.

Possibly some of this has to do with the fact that Nicholas of Hereford was taken into custody around 1390 and went from clerical rebel to persecutor himself, being involved in the punishment of his former colleagues.

Also, although we refer to early and late Wycliffite versions, there are mixed manuscripts. Or, at least, block mixed texts -- copies were some books may be in the early and some in the late translation. (There does seem to be one manuscript that has a genuinely mixed text of the two versions, but it is very much the exception.)

The late Wycliffite version actually inspired a secondary version: Some time around the late fifteenth century, it was translated into Scots by a translator named Murdoch Nisbet.

Also, although the complete Middle English versions are Lollard translations, there were several partial Middle English versions, usually of portions of the New Testament. These were often more free than Wycliffe's, and they are in various dialects, northern and southern. Most were probably from the Vulgate, but at least one, a commentary version of the Apocalypse from the North Midlands, was based on an Anglo-Norman French original.

The standard edition of both Wycliffite versions for most of the last century and a half has been Josiah Forshall and Frederic Madden, The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments, in the earliest English version made from the Latin Vulgate by John Wycliffe and his followers (in four volumes, Oxford, 1850). It cites many manuscripts and had a critical text, but of course is now badly out of date.

It is often stated that there was no attempt whatsoever to create English translations of the Bible between the Norman Conquest and Wycliff. This statement is perhaps a little too simplistic. It is certainly true that there is no evidence, either literary or historical, of an attempt to create a continuous-text translation prior to Wycliff. There is, however, a work called the Northern Homily Cycle, which exists in some twenty manuscripts and at least three recensions, which consists of a sermon for particular weeks and (in the earlier copies) includes an English paraphrase of the texts around which the sermon is built. Collectively these contain a large amount of Biblical text (translated from the Vulgate, to be sure). As a text-critical document, it has no appreciable value (which is just as well, since there is no critical edition; indeed, there is no non-critical edition nor even a diplomatic edition of the text of the primary recension). And it's not a complete rendering. But it should probably be mentioned, since it is more than a mere collection of allusions even if it's less than a complete text. Those wishing to see what part of it is like may consult Anne B. Thompson, editor, The Northern Homily Cycle, TEAMS Middle English Texts, 2008, which contains about a third of it.

Arabic

|

Arabic translations of the New Testament are numerous. They are also very diverse. They are believed to have been made from, among others, Greek, Syriac, and Coptic exemplars. Possibly there are other sources as well. |

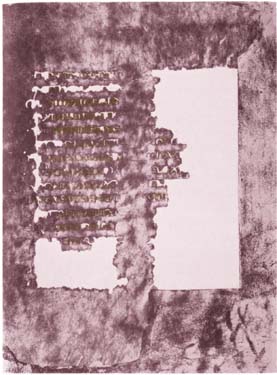

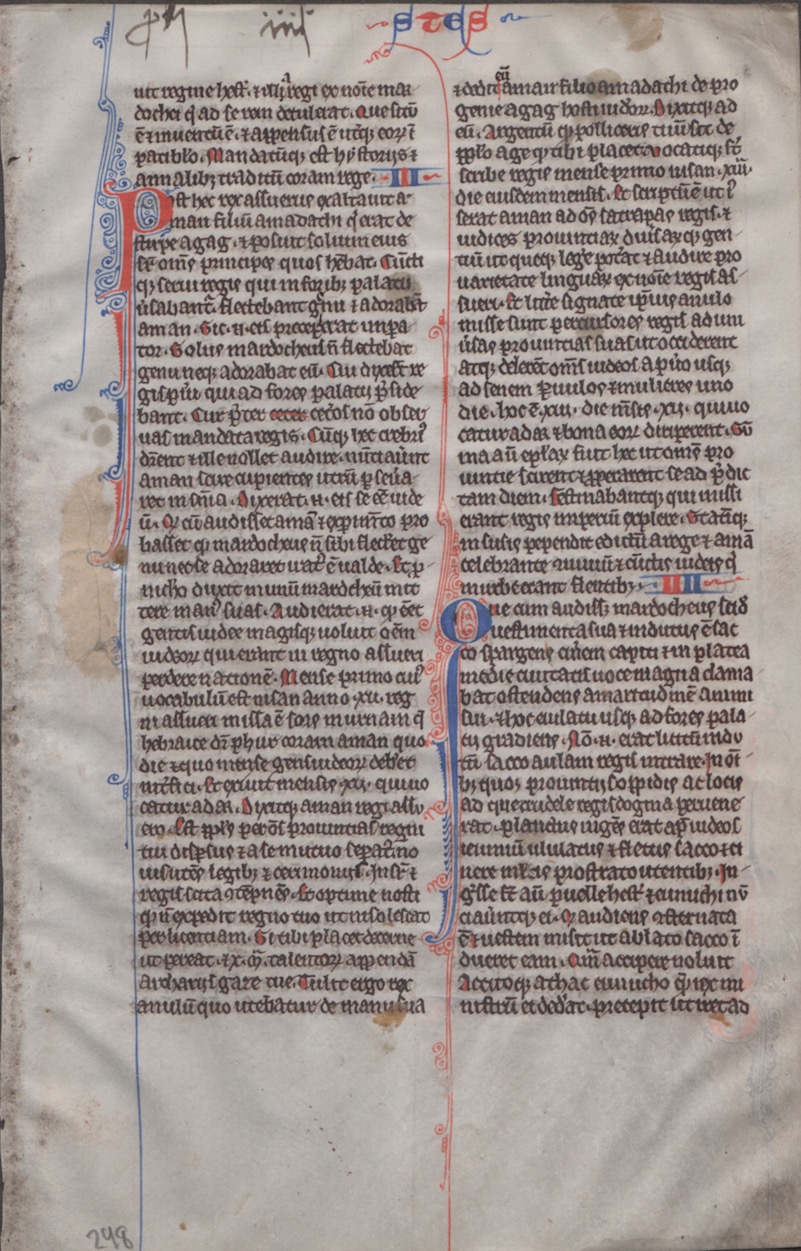

Folio 1 recto of Sinai Arabic 71 (Xth century), Matthew 23:3-15. |

Although there are hints in the records of Arabic versions made before the Islamic conquests, the earliest manuscripts seem to date from the ninth century. (It has been argued forcefully that Mohammed did not have access to an Arabic translation of the New Testament, since he seems to have had only hints of its content, perhaps tainted by Docetism. This strikes me as likely, given the errors about Christianity found in the Quran, but the secondary conclusion that no Arabic translation existed in his time does not follow.) The oldest dated manuscript of the version (Sinai arab. 151) comes from 867 C.E. The translations probably are not more than a century or two older.

Several of the translations are reported to be very free. In any case, Arabic is a Semitic language (which, like Hebrew, has a consonantal alphabet, leaving room for interpretation of vowels) and frequently cannot transmit the more subtle nuances of Greek grammar. In addition, written Arabic was largely frozen by the Quran, while the spoken language continued to evolve and develop regional differences. (Many modern "Arabics" are mutually incomprehensible.) This makes the Arabic versions somewhat less vernacular than other translations. This would probably tend to preserve the original readings, but may result in some rather peculiar variants.

The texts of the Arabic versions have not, to this point, been adequately studied. Some seem to be purely or primarily Byzantine, but at least some are reported to contain "Cæsarean" readings. Others are said to be Alexandrian. Still others, with something of an "Old Syriac" cast, may be "Western."

Several late manuscripts preserve an Arabic Diatessaron. The text exists in two forms, but both seem to have been influenced by the Peshitta. They are generally regarded as having little value for Diatessaric studies.

It will be obvious that the Arabic versions are overdue for a careful study and classification.

Armenian

The Armenian translation of the Bible has been called "The Queen of the Versions."

The title is probably deserved. The Armenian is unique in that its rendering of the New Testament is clear, accurate, and literal -- and at the same time stylisticly excellent. It also has an interesting underlying text.

The origin of the Armenian version is mysterious. We have some historical documents, but these may raise more questions than they solve. Even the name is, arguably, inaccurate; Armenians call their language "Hayaren" and their country "Hayastan."

The most recent summary on the version's history, that of Joseph M. Alexanian, states that the initial Armenian translation (Arm 1) was made from the Old Syriac in 406-414 C.E. This was followed by a revised translation (Arm 2) made from the Greek after the Council of Ephesus in 431. He suggests that further revisions followed.

In assessing Alexanian's claims, one should keep in mind that there are no Armenian manuscripts of this era, and the patristic citations, while abundant, have not been properly studied or catalogued.

Armenia is strongly linked with Syrian Christianity. The country turned officially Christian before Constantine, in an era when the only Christian states were a few Syriac principalities such as Edessa. One would therefore expect the earliest Armenian versions to show strong signs of Syriac influence.

The signs of Syriac influence exist (among them, manuscripts with 3 Corinthians and without Philemon) -- but so do signs of Greek influence. The text of the Armenian matches neither the extant Old Syriac nor the Peshitta. It appears to be much more closely linked with the "Cæsarean" text. In fact, the Armenian is arguably the best witness to that text.

The history of the Armenian version is closely tied in with the history of the written Armenian language. After perhaps an unsuccessful attempt by a cleric named Daniel, the Armenian alphabet is reported to have been created by Mesrop, the friend and co-worker of the Armenian church leader Sahak. The year is reported to have been 406, and the impetus for the invention is said to have been the need for a way to record the Armenian Bible. Said translation was finished in the dozen or so years after Mesrop began his work.

This history does not convince all scholars, who point out that our earliest Armenian writings do not look as if they are the first products of a written language. Written Armenian, as found in the Bible and other early writings, looks like a language with a rich literary history -- which hints that written Armenian existed before Mesrop. Dialects are also an issue; although the orthography of early Armenian does not show signs of variations in speech, modern Armenian has about sixty different dialects (which are substantially different, since the differences involve even such things as how the present tense of verbs is marked), and many believe there were dialects at the time the version was translated -- which raises the issue of which dialect was used for the translation.

Despite Alexanian, the basis of the version also remains in dispute. Good scholars have argued both for Syriac and for Greek. There are passages where the wording seems to argue for a Syriac original -- but others that argue equally forceably for a Greek base.

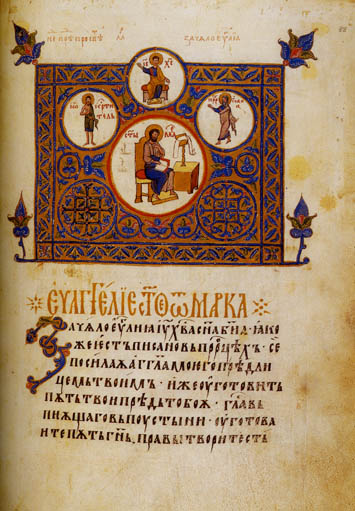

|

A portion of one column of the famous Armenian MS. Matenadaran 2374 (formerly Etchmiadzin 229), dated 989 C.E. Often called the Ējmiacin Gospels. Mark 16:8-9 are shown. The famous reference to the presbyter Arist(i)on is highlighted in red. | At least three explanations are possible for this. One is that the Armenian was translated from the Greek, but that the translator was intimately familiar with a Syriac rendering. An alternate proposal is that the Armenian was translated in several stages. The earliest stage was probably a translation from one or another Old Syriac versions, or perhaps from the Syriac Diatessaron. This was then revised toward the Greek, perhaps from a "Cæsarean" witness. Further revisions may have increased the number of Byzantine readings. Finally, there may have been two separate translations (Conybeare suggests that Mesrop translated from the Greek and Sahak from the Syriac) which were eventually combined. |

The Armenian "Majority Text" has been credited to Nerses of Lambron, who revised the Apocalypse, and perhaps the entire version, on the basis of the Greek in the twelfth century. This late text, however, has little value; it is noticeably more Byzantine than the early text. It is noteworthy that the longer ending of Mark does not become common in Armenian manuscripts until the thirteenth century. Fortunately, the earliest Armenian manuscripts are much older than this; a number date from the ninth century. The oldest dated manuscript comes from 887 C.E. (One manuscript claims a date of 602 C.E., but this is believed to be a forgery.)

There are a few places where the Armenian renders the Greek rather freely (usually to bring out the sense more clearly); these have been compared to the Targums, and might possibly be evidence of Syriac influence.

The link between the Armenian and the "Cæsarean" text was noticed early in the history of that type; Streeter commented on it, and even Blake (who thought the Armenian to be predominantly Byzantine) believed that it derived from a "Cæsarean" form. The existence of the "Cæsarean" text is now considered questionable, but there is no doubt that the early Armenian testifies to a text which is far removed from the Byzantine, and that it contains large numbers of Alexandrian readings as well as quite a number associated with the "Western" witnesses. The earliest witnesses generally either omit "Mark 16:9-20" or have some sort of indication that it is doubtful (the manuscript shown here may credit it to the presbyter Arist(i)on, though this remark is possibly from a later hand). "John 7:53-8:11" is also absent from most early copies.

In the Acts and Epistles, the Armenian continues to display a text which is not Byzantine but not purely Alexandrian either. Yet -- in Paul at least -- it is not "Western." Nor does it agree with family 1739, nor with H, both of which have been labelled (probably falsely) "Cæsarean." If the Armenian has any affinity in Paul at all, it is with family 2127 -- a late Alexandrian group with some degree of mixture. This is not really surprising, since one of the leading witnesses to the family is 256, a Greek/Armenian diglot (in fact, the Armenian text of 256 is one of the earliest witnesses to the Armenian Epistles).

Lyonnet felt that the Armenian text of the Catholic Epistles fell close to Vaticanus. In the Apocalypse, Conybeare saw an affinity to the Latin (in fact, he argued that it had been translated from the Latin and then revised -- as many as five times! -- from the Greek. This is probably needlessly complex, but the Latin ties are interesting. Jean Valentin offers the speculation that the Latin influence comes from the Crusades, when the Armenians and the Franks were in frequent contact and alliance.)

The primary edition of the Armenian, that of Zohrab, is based mostly on relatively recent manuscripts and is not really a critical edition (although some variant readings are found in the margin, their support is not listed). Until a better edition of the version becomes available -- an urgent need, given the quality of the translation -- the text of the version must be used with caution.

Coptic

The language of Egypt endured for at least 3500 years before the Islamic conquest swept it aside in favour of Arabic. During that time it naturally underwent significant evolution.

There was at one time much debate over the origin of the Egyptian language; was it Semitic or not? It seemed to have Semitic influence, but not enough to really be part of the family. This seems now to have been solved; Joseph H. Greenburg in the 1960s proposed to group most of the languages of northern Africa and the Middle East in one great "Afroasiatic" superfamily. Egyptian and the Semitic languages were two of the families within this greater group. Thus Egyptian is related to the Semitic languages, but at a rather large distance.

Coptic is the final stage of the evolution of Egyptian (the words "Copt" and "Coptic" are much-distorted versions of the name "Aigypt[os]"). Although there is no clear linguistic divide between Late Egyptian and Coptic, there is something of a literary one: Coptic is Egyptian written in an alphabet based on the Greek. It is widely stated that the Coptic alphabet (consisting of the twenty-four Greek letters plus seven letters -- give or take a few -- adopted from the Demotic) was developed because the old Egyptian Demotic alphabet was too strongly associated with paganism. This seems not to be true, however; the earliest surviving documents in the Coptic alphabet appear to have been magical texts.

The following table shows these additional letters -- the left side using unicode symbols, the right side being an equivalent (but low-res) graphic in case your system doesn't support those unicode symbols. (Note that unicode doesn't really support demotic lettering; I did the best I could.)

| demotic: | Ϣ | Ϥ | 9 | IL | σ | 𝚝 |

| |

| Coptic: | Ϣ | Ϥ | Ϩ | Ϫ | Ϭ | Ϯ | ||

| pronounced: | sh | f | h | j | g | ti |

It is at least reasonable to suppose that the Coptic alphabet was adopted because it was an alphabet -- the hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic styles of Egyptian are all syllabic systems with ideographic elements. And both hieratic and demotic have other problems: Hieratic is difficult to write, and demotic, while much easier to copy, is difficult to read. And neither represents vowels accurately. Some scribe, wanting a true alphabetic script, took over the Greek alphabet, adding a few demotic symbols to supply additional sounds.

Coptic finally settled down to use the 24 Greek letters plus six or seven demotic symbols. It was some time before this standard was achieved, however; early texts often use more than these few extra signs. This clearly reveals a period of experimentation.

Coptic is not a unified language; many dialects (Akhmimic, Bohairic, Fayyumic, Middle Egyptian, Sahidic) are known. The fragmentation of Coptic is probably the result of the policies of Egypt's rulers: The Romans imposed harsh controls on travel in and out of, and presumably within, Egypt; before them, the Ptolemies has rigidly regimented their subjects' lives and travels. After a few hundred years of that, it is hardly surprising that the Egyptian language fragmented into regional forms.

New Testament translations have been found in all five of the dialects listed; in several instances there seem to have been multiple translations. The two most important, however, are clearly Sahidic (the language of Upper Egypt) and Bohairic (used in the Lower Egyptian Delta). Where the other versions exist only in a handful of manuscripts, the Sahidic endures in dozens and the Bohairic in hundreds. The Bohairic remains the official version of the Coptic church to this day, although the language is, for practical purposes, extinct in ordinary life.

The history of the Coptic versions has been separated into four stages by Wisse (modifying Kasser). For convenience, these stages are listed below, although I am not sure of their validity.

- The Pre-Classical Stage, 250-350 C.E. First attempts at translation, which had little influence on the later versions.

- The Classical Sahidic and Fayyumic Stage, 350-450 C.E. Preparation of versions for use by those who had no Greek. The Sahidic becomes the dominant version. Other versions, notably the Fayyumic, circulate but are not widespread.

- The Final Sahidic and Fayyumic Stage, 450-1000 C.E. The Arab conquest reduces the role and power of the Coptic church. The Sahidic begins to decline.

- The Bohairic Stage, after 800 C.E. The Bohairic version becomes standardized and gradually achieves dominance within the Coptic church.

A more detailed study of the various versions follows.

The Sahidic Coptic

The Sahidic is probably the earliest of the Coptic translations (certainly of the substantial ones), and also has the greatest textual value. It came into existence no later than the third century, since a copy of 1 Peter exists in a manuscript from about the end of that century. Unlike the Bohairic version, there is little evidence of progressive revision. The manuscripts do not always agree, but they do not show the sort of process seen in the Bohairic Version.

Like all the Coptic versions, the Sahidic has an Egyptian sort of text. In the Gospels it is clearly Alexandrian, although it is sometimes considered to have "Western" variants, especially in John. (There are, in fact, occasional "Western" readings in the manuscripts, but no pattern of Western influence. Most of the so-called "Western" variants also have Alexandrian support.) As between B and ℵ, the Sahidic is clearly closer to the former -- and if anything even closer to P75. It is also close to T (a close ally of P75/B) -- as indeed one would expect, since T is a Greek/Sahidic diglot.

In Acts, the Sahidic is again regarded as basically Alexandrian, though with some minor readings associated with the "Western" text. In the "Apostolic Decree" (Acts 15:19f., etc.) it conflates the Alexandrian and "Western" forms. (One should note, however, the existence of the codex known as Berlin P. 15926. Although its language is said to be Sahidic, its text differs very strongly from the common Sahidic version, and preserves a number of striking "Western" variants found also in the Middle Egyptian text G67.)

In Paul the situation is slightly different. Here again at first glance the Sahidic might seem Alexandrian with a "Western" tinge. On examination, however, it proves to be very strongly associated with B, and also somewhat associated with B's ally P46. I have argued elsewhere that P46/B form their own text-type in Paul. The Sahidic clearly goes with this type, although perhaps with some influence from the "mainstream" Alexandrian text.

In the Catholics, the Sahidic seems to have a rather generic Alexandrian text, being about equidistant from all the other witnesses. It is noteworthy that its more unusual readings are often shared with B.

The Bohairic Coptic

The Bohairic has perhaps the most complicated textual history of any of the Coptic versions. The oldest known manuscript, Papyrus Bodmer III, contains a text of the Gospel of John copied in the fourth (or perhaps fifth) century. This version is substantially different from the later Coptic versions, however; the underlying text is distinct, the translation is different -- and even the form of the language is not quite the same as in the later Bohairic version. For this reason it has become common to refer to this early Bohairic version as the "proto-Bohairic" (pbo). From the same era comes a fragment of Philippians which may be a Sahidic text partly conformed to the idiom of Bohairic.

Other than these two minor manuscripts, our Bohairic texts all date from the ninth century or later. It is suspected that the common Bohairic translation was made in the seventh or eighth century.

It is quite possible that this version was revised, however; there are a number of places where the Bohairic manuscripts split into two groups. Where this happens, it is fairly common to find the older texts having a reading typical of the earlier Alexandrian witnesses while the more recent manuscripts often display a reading characteristic of more recent Alexandrian documents or of the Byzantine text. One can only suspect that these late readings were introduced by a systematic revision.

As already hinted, the text of the Bohairic Coptic is Alexandrian. Within its text-type, however, it tends to go with ℵ rather than B. This is most notable in Paul (where, of course, ℵ and B are most distinct). Zuntz thought that the Bohairic was a "proto-Alexandrian" witness (i.e. that it belonged with 𝔓46 B sa), but in fact it is one of ℵ's closest allies here -- despite hints of Sahidic influence, which are found in the other sections of the New Testament as well. One might theorize that the Bohairic was translated from the Greek (based on a manuscript with a late Alexandrian text), but with at least some Sahidic fragments used as cribs.

The Lesser Coptic Versions

The Akhmimic (Achmimic). Possibly the most fragmentary of all the versions. Fragments preserve portions of Matthew 9, Luke 12-13, 17-18, Gal. 5-6, James 5. All of these seem to be from the fourth or perhaps fifth centuries. Given their small size, very little is known of the text of the Akhmimic. Aland cites it under the symbol ac. The Editio Critica Maior in James cites it as K:A.

Related to the Akhmimic, and regarded as falling between it and the Middle Egyptian, is the Sub-Akhmimic. This exists primarily in a manuscript of John, containing portions of John 2:12-20:20 and believed to date from the fourth century. It seems to be Alexandrian, and is cited under the symbol ac2 or ach2.

The Fayyumic. Spelled Fayumic by some. Many manuscripts exist for the Gospels, and over a dozen for Paul, but almost all are fragmentary. Manuscripts of Acts and the Catholic Epistles are rare; the Apocalypse seems to be entirely lost (if, indeed, it was ever translated). Manuscripts date from about the fifth to the ninth centuries. There is also a fragment of John, from perhaps the early fourth century, which Kahle called Middle Egyptian but Husselman called Fayyumic. This mixed text is now designated the "Middle Egyptian Fayyumic (mf)" by Aland. (The Fayyumic is not cited in NA27; the abbreviation fay is used in UBS4.)

Given the fragmentary state of the Fayyumic, its text has not been given much attention. In Acts it is reported to be dependent on the Bohairic, and hence to be Alexandrian. Kahle found that an early manuscript which contained both the long and short endings of Mark.

The Middle Egyptian. The Middle Egyptian Coptic is represented primarily by three manuscripts -- one of Matthew (complete; fourth/fifth century), one of Acts (1:1-15:3; fourth century), and one of Paul (54 leaves of about 150 in the original; fifth century). The Acts manuscript, commonly cited as copG67, is perhaps the most notable, as it agrees frequently with the "Western" witnesses, including some of the more extravagant variants of the type. The Middle Egyptian is cited by Aland under the symbol mae; UBS4 uses meg.

Ethiopic

This is one of the more difficult sections in this article. My original sources on Ethiopic -- Metzger and older authors, plus the first edition of Ehrman & Holmes's The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research -- gave an account which, I suspect, was not based on sufficient information to be accurate. Tom Hennell has given me a good deal of additional information, much of which does not agree with the implications of the earlier sources. What follows is mostly his revision of what I originally wrote, but I am going to indent the portions which are almost entirely his work. Other than conforming his style to my style book and turning it to HTML, my only changes to his text are marked in [ ]. I am not saying his words are dubious; they are simply sections which I have not researched or verified, and which often disagree with the (not sufficiently researched) writings of Metzger et al.

Although the origins of many of the versions are obscure, few are as obscure as those of the Ethiopic. The legend that Christianity was carried to the land south of Egypt by the eunuch of Acts 8:26f. can be easily dismissed. So can accounts that one of the apostles worked there. Even if one or more of these stories were true, they would not explain the existence of the Ethiopic version -- for the good and simple reason that the New Testament hadn't even been written at the time of the Ethiopian's conversion in Acts.

Even the name of the version is questionable; the name "Ethiopia" was applied by Greeks, Jews and Romans without distinction to any part of sub-Saharan Africa. The correct name for the official language of modern Ethiopia is Amharic, and the manuscripts of the "Ethiopic" version are sometimes said to be in an old form of this language. (There are actually printed Bibles in Ethiopia which put an "old Ethiopic" text in parallel with a modern Amharic version.)

The Ethiopic version originated in the Kingdom of Axum, named after its capital city in the Abyssinian highlands; but which through its port of Adulis on the Red Sea (in modern Eritrea) had by the late 3rd century established control over the rich trade route in luxury goods between the late Roman Empire and India. Consequently (and confusingly) late Antique writers frequently refer to Axum as "India." The Axumite kingdom was multilingual, although only two of its languages were regularly written in this period. The trading community at Adulis spoke Greek, as did the royal court at Axum; but the literate populations of Axum and the highlands spoke and wrote in Ge'ez, a Semitic language related to South Arabian. The kings' gold and silver coinage was inscribed in Greek; which was also carved, alongside Ge'ez, on the lengthy monumental inscriptions with which they celebrated their deeds. When, in the mid 4th century, the Axumites converted to Christianity, they then adopted the term "Ethiopians" as a conscious biblical self-identification. [Curt] Niccum suggests that they may have been prompted in this by a misreading of above the story in Acts; where the Greek text has the eunuch travelling to "Gaza," the Ethiopic version of Acts has him travelling to "the land of the Ge’ez."

Ge'ez then was to be the language of the Ethiopic New Testament, and in formal 4th century Axumite inscriptions this language is found in two scripts; Sabaean, the consonantal script commonly used for South Arabian inscriptions; and Ethiopic, also originally a consonantal script (like Hebrew and Arabic, but written from left to right), but which by this date was beginning to be "vocalised" such that the 7 vowel sounds were indicated by the addition of loops and tail-strokes to the 26 Ge'ez consonantal signs. Surviving informal written Ge'ez of this date -- generally as graffiti on rocks and pots -- always uses Ethiopic. Strictly therefore, "Ge'ez" denotes the language; while "Ethiopic" denotes the script. Ge'ez itself ceased to be an everyday vernacular by the tenth century C.E. but continued and continues as the liturgical language of the Ethiopian church. [Rather as Akkadian continued to be used as a diplomatic language in the Middle East long after it ceased to be used in ordinary life. - RBW] From the 13th century onwards, large numbers of religious works in Coptic Arabic were translated into Ge'ez; in turn leading to the creation of a vigorous indigenous Ge'ez literary tradition (chiefly hagiographic) up till around 1900. Of modern languages, Tigrinya and Tigre (predominant in Eritrea and the north of Ethiopia) are descended from Ge’ez, while Amharic (predominant in the south and around Addis Ababa) derives from a separate stream of South Semitic. The Ethiopic script is still used to write the all Semitic languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Since vocalised Ethiopic, with over 200 symbols, is a great deal easier to write than print, Ethiopian churches and monasteries have continued to rely on manuscript book production to the present day. Consequently even small churches may house dozens of manuscript books; including biblical texts, translations from Coptic Arabic, and original compositions in Ge'ez. Valuable medieval and previously unknown texts continue to be recognised in these remote libraries.

A legend told by Rufinus has it that Christianity reached Ethiopia to stay in the fourth century. We now know this to be true:

Christianity was formally adopted as the religion of Axum by King Ezana around the year 340. That much is definite; as Ezana then changed the coinage to incorporate cross symbols around his portrait; and, in the Greek text of a multilingual inscription found in Axum, invoked the Trinity, declaring himself to be the "servant of Christ" and designating Christ as "the god in whom I have believed." Furthermore Ezana promptly acted to acquire a bishop for his new church; dispatching Frumentius, a Greek originally from Tyre, to Egypt to be consecrated as the first bishop of Axum by Athanasius, the patriarch of Alexandria. Phillipson points out, however, that the counterpart Ge'ez text for the multilingual inscription lacks the key phrases above; Ezana’s Christianity appears originally to have been observed only in Greek.

In 356 however, the Byzantine emperor Constantius II acted to remove Athanasius; replacing him as Patriarch by the Arian (or semi-Arian), George of Cappadocia. Constantius then wrote to Ezana denouncing Athanasius, and requesting that Frumentius be recalled to Alexandria to be re-instructed by George. Ezana appears not to have responded; indeed a diplomatic mission that Constantius sent to Axum in 357 kicked their heels in Egypt for over a year, unable to proceed south. More particularly, Ezana and his successors appear to have resolved to withdraw from participation in the ongoing bitter Christological controversies of the 4th and 5th centuries; no Ethiopian cleric is recorded as attending any of the succession of councils and synods over the following hundred years. The policy of religious isolation may also have been the impetus for a decision to translate the Bible into Ge'ez. In the late 380s John Chrystostom claimed that the Gospel of John had recently been translated by the Ethiopians into their own language. Official isolation did not, it seems, impede individual Axumite Christians from continuing to travel within the Byzantine empire; Jerome in Bethlehem in the early 5th century reported encountering "crowds" of Ethiopian monks and pilgrims.

Negatively, the translators’ limited command of Greek severely detracted from their resulting version. Worst affected is the Acts of the Apostles, where substantial sections of chapters 27 and 28, with their nautical terminology, entirely defeated the translator, who simply omitted them. But generally, when faced with text they did not understand, the translators paraphrased, guessed or omitted; resulting in "wild" readings. [In addition, since they seem to have been] reading Greek texts written in "scriptio continua," words and sentences are frequently wrongly divided. Moreover, the translators show little appreciation of Greek particles, or of the case endings of Greek nouns; consequently proposing readings that are grammatically untenable in the original.

Much that is distinctive about the Ethiopic version can be understood in this context. It was not created by missionaries from outside, nor under the direction of the Alexandrian patriarchate; the translator "worked with absolutely nothing beyond the Greek manuscript that lay before him or her" (Niccum). From the perspective of modern scholarship, this had both positive and negative effects. Positively, Ethiopian translators seized eagerly on each and every Greek biblical text they could find in the Christian world of the mid 4th century; unconstrained by questions of canonicity. So not only did the Ethiopian version come to include all the books later to be accepted into the canons of Old and New Testaments (plus the works commonly recognised in the Biblical Apocrypha); the version also translated the first Book of Enoch, the Book of Jubilees, the Ascension of Isaiah and the Paralipomena of Jeremiah; together with (in the New Testament) the Shepherd of Hermas and the Acts of Mark. In respect of the Old Testament titles, these works now survive complete only in Ethiopic.

If the translation of the scriptures into Ethiopic started in the later 4th century, most likely with the Gospels and Psalms, there has been much debate in western scholarship as to when the programme may have been fully completed. In particular, a number of western scholars had seized on the Ethiopian tradition that the rural areas of Axum had been Christianised due to the labours of "Nine Saints," monks arriving from "Rome" [i.e. Byzantium? - RBW] in the fifth and sixth centuries who are celebrated as the founders of a series of great monasteries in this period. It was proposed that these monks might be monophysite clergy from Syria relocating to Ethiopia following the Council of Chalcedon of 451; and that the work of translating the majority of the Bible should therefore be credited to these missionaries and their successors; proceeding over an extended period in the sixth and seventh centuries and likely taking the Syriac Peshitta as its base.

Knibb has pointed out though, that this narrative is unsupported in the Ethiopian sources themselves. In these sources, none of the "Nine Saints" is proposed as being a translator, and only two are associated with a Syrian origin. Moreover, the distinctive pattern of translation errors (discussed above) demonstrates that all the books of the Old and New Testaments were translated primarily from the Greek. Why would Syrian monks choose to work from a Greek text, especially one they appear not to have fully understood?

Formal relations were restored between the church of Axum and the Alexandrian patriarchate some time in the late fifth century; and Niccum has expressed the more recent consensus, that the whole of the Bible had been translated into Ge'ez by this date. He puts forward three arguments; firstly, that there is no evidence for a continued indigenous Greek literacy capable of supporting a translation enterprise in Axum after the fifth century, neither around Adulis nor in the royal court; secondly, that monumental Ge'ez inscriptions celebrating the Axumite king Kaleb, dated around 525, contain numerous quotations from the Ethiopic version, taken from Exodus, Psalms, Isaiah and Matthew, and suggesting that a complete bible was then available; and thirdly that the "extra" books in the Axumite biblical canon could only have been translated in the period of religious isolation, as two of them (1 Enoch and the Ascension of Isaiah) had been condemned as heretical by Athanasius in his festal letter of 367. Niccum proposes it as most likely that the undisputed "canonical" books would have been translated before these "extra" books.

But it is one thing to date the earliest Ethiopic version; it is another to recognise it in the surviving manuscript record. Most of the Axumite territory fell to the Muslim armies of Ahmad Gragn in the period 1531-1543; churches and monasteries were looted and manuscripts systematically destroyed. Consequently very few medieval manuscripts survive. Moreover the two standard western printed editions of the Ethiopic version -- the Roman New Testament of 1548, and Thomas Pell Platt’s BFBS Bible of 1830 -- have little critical value; and consequently the siglum "Eth" for readings in former critical New Testament editions is often misapplied. But fortunately, over the last fifty years, almost the whole of the Ethiopic New Testament has been published, book by book, in critical editions; the Gospel of Luke still being outstanding. For almost all the books the characterisation of manuscript sources emerging in these editions is similar; A-texts, as the earliest recoverable text descended from the original Axumite version six or seven centuries earlier; medieval Ab-texts, essentially the A-text with its more egregious errors corrected with reference to Coptic Arabic manuscripts from the 13th century onwards; and B-texts of 15th/16th century date, representing a more systematic reworking of the Ab-texts to conform with Coptic Arabic models B-text readings are commonly closer to the Greek than A-text readings, even though most likely accessing the Greek indirectly through the medium of a literal Arabic version. There is no doubt that the B-texts consistently provide a far superior representation of scripture; but only the A-texts have independent critical value as a witness to the Greek. Fortunately, as Ethiopian scribes commonly preferred to correct by conflation rather than replacement, critical editors can often reckon to recover the A-text readings by identifying and removing the "B/b" corrections. One consistent finding in these critical editions is that most of the supposed "Syriac" or "Western" readings advanced by proponents of Syrian or Coptic influence on the Ethiopic text, turn out to be found in the B-text; and hence are likely to be disguised "Arabisms.".

Outside the Gospels, even identified A-text manuscripts are no older than the 14th century. But since the 1960s, it has been recognised that the oldest Gospel manuscripts -- the two complete Garima Gospels -- are very much older. Just how much older has only become clear in the last few years, as both have been carbon dated to the 6th century; Garima 2 having a date range of 390-570. So these manuscripts uniquely are contemporary with the Axumite kingdom at the height of its power. As they are not copied from one another, their combined witness allows us to access the Axumite archetype text of the Ethiopic Gospels with a degree of confidence. Moreover, by checking against medieval A-text manuscripts, we can confirm that the Axumite translations of the Gospels happened only once. Only in the first four verses of Luke do we find a variant ancient translation in the medieval tradition.

The Ethiopic A-texts display a number of common characteristics -- over and above the pattern of errors arising from poor command of biblical Greek.

- Ge'ez syntax generally expects explicit subjects and objects to the verb, and the A-text supplies these; so "and then he said..." becomes "and then Jesus said to them...."

- Translators liberally add "all" and "much" into sentences, as intensifiers

- Translations show an "extreme tendency to harmonization" (Zuurmond) both where similar wording is found across synoptic parallels, and also where different narratives share a similar context (as for instance where the phrase "In the beginning..." from the Gospel of John is also found at Acts 1:1, and Mark 1:1)

- Translations also show a strong tendency to dual and multiple readings; where the same Greek term is translated or transliterated differently, even when only one or two verses apart (or indeed when the same term is translated in one verse and transliterated in the next).

- Overall the A-text of the Gospels shows characteristics of a first draft, wording is typically "free" and is inclined to simplify. Only a few short Gospel passages are translated word-for-word. The other New Testament A-text translations are generally more literal. Much of the Old Testament is considered by Knibb to be "almost slavishly literal in rendering the Septuagint Greek.

Allowance must be made for these characteristics when seeking to establish the underlying text-form Ethiopic A-text. It can readily be determined that the translation base -- for both Old and New Testaments -- was always and exclusively Greek; although it is rarely possible to retrovert to an exact Greek text with confidence, purely from the Ethiopic A-text. The textual base of the B-text is not quite so certain, other in the specific case of the Book of Acts where Niccum has determined that B-text derives from a known literal Arabic version of the Syriac. (There survives in Milan a 14th century tetraglot manuscript -- Coptic, Syriac, Arabic and Ethiopic -- containing Acts and the Catholic Epistles. The Ethiopic column there is the primary witness to the Niccum's A-text, and it is straightforwardly demonstrable that the B-text manuscripts from the 15th/16th centuries derive from the version in the Arabic column which itself translates the Syriac; not the least because a marginal note at Chapter 28 of that Arabic version is appended to the B-text to create the Ethioipic "Longer Ending" of Acts.) It is not impossible that all the other B-texts have a similar origin; although critical knowledge of Arabic versions is not yet sufficient to confirm this. The only book where this may not be the case is the Gospel of Matthew, where a B-text was produced much earlier (11th/12th century); Zuurmond has speculated that an Egyptian Greek text, adjusted to conform with with a later Arabic version, could underlie this text.

It is, however, commonly possible to cross-reference the A-text against established lists of variant readings in the New Testament Greek, so as to establish whether the Ethiopic is more likely to support one or another text-type.

Outside the Gospels, cross-referencing always demonstrates a strong affinity between the A-text and the Alexandrian text. In the Book of Acts, Niccum finds the closest correspondence is with the surviving text in 𝔓45 rather than with Vaticanus or Sinaiticus. Hofmann found the text of Ethiopic Revelation as standing closest to Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus, and Ephraemi. Uhlig has confirmed an Alexandrian text for the Pauline epistles, and (showing a greater degree of Byzantine influence) for the Catholic letters.

The position of the Gospels is different, and more varied. In the Gospel of Matthew, Zuurmond finds the A-text as more likely to support early Byzantine readings over Alexandrian readings by around 3:1. In the Gospel of John, the proportion of Byzantine readings is closer to even. In Mark, the pattern is similar to that in Matthew, except in the earliest chapters which tend to align with the Codex Washingtonensis (and hence, the Western text-type). Overall though, Zuurmond characterises the A-text in the Gospels as early Byzantine; "the A-text was based on a Greek text of mixed character, not yet completely dominated by the Byzantine type -- likely indicating this as the form of text that circulated in Egypt in the mid 4th century." This implies that, alongside the Gothic version and the Peshitta, the Ethiopic text of the Gospels provides the earliest witnesses to the form taken by the Byzantine text in the mid 4th century.

Of particular readings, the A-text always witnesses the Longer Ending to Mark (the Shorter Ending is sometimes found preceding the Longer Ending in the B-text). In Matthew, the A-text includes 16:2-3 (the red skies and the signs of the times); and also at 24:36, the A-text includes "nor the Son." The Pericope Adulterae is always absent from John 7:53-8:11. One unexpected reading in the A-text is at John 5:3-4; where Ethiopic might have been expected to have omitted the whole of the presumed secondary addition found in the Majority Text, but actually includes the verse sections 3b and 4a, "They were waiting for the disturbing of the water. For an angel of the Lord at the right time washed himself in the pool and the water was disturbed," while omitting the rest of verse 4.

A specific uncertain reading where the contribution of Ethiopic version may be of interest, is the Western non-interpolation at Matthew 27:49, where the best and earliest Alexandrian witnesses, the commentary of Chrysostom, and the early Coptic papyri all support the text "...and someone else, taking a spear, pierced his side and there came out water and blood"; words which are otherwise absent from the Western versions, from Bezae, Alexandrinus and Washingtonensis, and from the majority of later witnesses (though far from all of them; the longer reading is consistently found in Irish gospels). There is indeed considerable evidence for the longer reading being removed from the 6th century onwards; both in the form of manuscripts where it has been marked for deletion, and also in accounts of authoritative condemnations of the longer text.

A similar passage is familiar from John 19:34, but with the order reversed, "blood and water," and with other differences in wording; but most crucially, John reports the piercing as occurring after Jesus’s death, whereas in the Matthew reading it is apparently the spearthrust itself that kills. In the Ethiopic, Garima 2 (the older of the two Axumite manuscripts) supports the exact Alexandrian wording, while Garima 1 reads the same, but with the order "blood and water"; and is followed in this by the rest of the A-text tradition.

There is little doubt that the event as described is unhistorical; Roman guards did not dispatch crucified criminals with their spears (prolonging death was the whole point), and these words are clearly an intrusion into the narrative of the crucifixion found in the Gospel of Mark. But might that addition be from Matthew himself; and if so, why? And, if not Matthew, why would anyone later insert it in such a prominent position, in clear contradiction to the Gospel of John? The witness of the Ethiopic version does not resolve these questions; but it does support the proposition that the longer reading stood in the standard text of Matthew in Egypt in the mid 4th century. In the standard critical editions, the major Coptic versions -– Bohairic and Sahidic -- are generally cited against the longer reading; but their manuscript witnesses to Matthew 27 are all much later. It may be suggested that the 4th century Bohairic and Sahidic are more likely to have included the longer reading.

That's the story according to New Testament scholars, at least, but there is dispute among secular linguists (who frankly seem to know a lot more about Georgian than the people who write about the Georgian version) whether the distinction between ẖan-meti/xanmet’i texts on the one hand and hae-meti/haemet’i on the other is chronological or dialectial -- which affects how we date our earliest fragments of the New Testament. Dialect differences would be no surprise; Modern Georgian, despite the small population, is divided into many, many dialects. (We refer to the period before the twelfth century as Old Georgian; the twelfth through eighteenth centuries constitute Middle Georgian, and the nineteenth century and after are the Modern Georgian period.) But there are too few fragments from the early period to let us know much about the dialects, and the first dictionary of Georgian was not prepared until 1716. The first printed Georgian book did not appear until the sixteenth century -- and it was prepared by outsiders; Georgia's first printing press did not open until around 1710.

The alphabet has also evolved; the earliest form, mrg(v)lovani, is a majuscule used from the fifth to ninth centuries; then came k’utxovani, an anguar minuscule with some resemblance to Armenian; starting from the eleventh century, the rounded mkhedruli/mxedruli came into use. Non-Biblical Georgian literature did not really begin until the twelfth century or so, so our only mrg(v)lovani texts are Bibles and commentaries.

By its nature it is difficult for Georgian to express many features of Greek syntax. This makes it difficult to determine the linguistic source of the version. (Nor does it help that the language itself has evolved; the translation started in Old Georgian, but later manuscripts will have been influenced by Middle Georgian and its dialects.) Greek, Armenian, and Syriac have all been proposed as translation bases -- in some instances even by the same scholar! It seems clear that the version was at some time in its history revised toward the Greek -- but since manuscripts of the unrevised text are at once rather few and divergent, we probably cannot reach a certain conclusion regarding the source at this time. The current opinion seems to be that, except in the Apocalypse (clearly taken from the Greek), the base text -- what we might call the "Old Georgian," and now found primarily in geo1 and some of the fragments -- was Armenian, and that it was progressively modified by comparison with the Greek text.

The earliest Georgian manuscripts are the already alluded to ẖan-met'i fragments of the sixth and seventh centuries, followed by the hae-met'i fragments of the next century. (The names derive from linguistic features of the Georgian which were falling into disuetitude.) These fragments are, unfortunately, so slight that (with the exception listed below) they are of little use in reconstructing the text (some 45 manuscripts contain, between them, fragments of the Gospels, Romans, and Galatians only). Recently a new ẖan-met'i palimpsest was discovered and published, containing large portions of the Gospels, but the details of its text are not yet known; it appears broadly to go with the Adysh manuscript (geo1).

With the ninth century, fortunately, we begin to possess fuller manuscripts, of good textual quality, from which we may attempt to reconstruct the "Old Georgian" text. Many of these manuscripts, happily, are dated.

The earliest substantially complete Georgian text is the Adysh manuscript, a copy of the Gospels dating from 897 C.E. It appears to have the most primitive of all Georgian translations, and is commonly designated geo1.

From the next century come the Opiza Gospels (913), the Džruč Gospels (936), the Parẖal Gospels (973), the Tbet’ Gospels (995), the Athos Praxapostolos (between 959 and 969), and the Kranim Apocalypse (978), as well as assorted not-so-well-known texts. Several of these manuscripts combine to represent a second stage of the Georgian version, designated geo2. When cited separately, the Opiza gospels are geoA, the Tbet’ gospels are geoB. (The Parẖal Gospels are sometimes cited as geoC, but this is not as common.)

Starting in the tenth century, the Georgian version was revised, most notably by Saint Euthymius of Athos (died 1028). Unfortunately, the resulting version, while perhaps improved in form and literary merit, is less interesting textually; the changes are generally in conformity with the Byzantine text.

The text of the Georgian version, in the Gospels, is strongly associated with the "Cæsarean" (assuming, of course, that text-type exists). Indeed, the Georgian appears to be, along with the Armenian, the purest surviving monument of that text-type. Both geo1 and geo2 preserve many readings of the type, though not always the same readings. Blake thought that geo1 affiliated with Θ 565 700 and geo2 with families 1 and 13.

In Acts, Birdsall links the Old Georgian to the later forms of the Alexandrian text found in minuscules such as 81 and 1175. In Paul, he notes a connection with 𝔓46, although this exists in scattered readings rather than as an overall affinity. In the Apocalypse, the text is that of the Andreas commentary.

Gothic

Of all the versions regularly cited in critical apparati, the Gothic is probably the least known. This is not because it is ignored. It is because it has almost ceased to exist.

Our information about the history of the Gothic is derived primarily from secondary sources, especially Auxentius, with some additional information from the church histories of Philostorgius, Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret. Thus the reliability of our information may be limited. What follows mostly assumes these sources are correct, because we have nothing else to consult.

The Gothic New Testament was apparently entirely the work of Ulfilas, the Apostle to the Goths. His mother is said to have been Cappadocian; his father presumably Gothic, since his proper name (variously recorded as Ulfila, Wulphilas, Vulfila, Ουλφιλας, and Ουρφιλας) was clearly Wulfila, the Little Wulf/Wolf. Born perhaps in 311, he was still very young when he was appointed Bishop to the Goths around 341 (serving also as a secular leader and taking his relatively few Christian Goths away from the persecutions of the leading Gothic nations). He spent the next forty years evangelizing and making the gospel available to his people. In the process he created the Gothic alphabet used for the translation. The graphics below show that it was based on Greek and Latin models, but also included some symbols from the Gothic runic alphabets.

The Gothic version includes both Old and New Testaments. The tradition is that Ulfilas translated it all, from the Greek, reportedly excepting the book of Kings, because it was too militant for his flock. This seems to be based on legends perpetuated by Auxentius and Socrates, however; Wright declares that the part about Ulfilas not translating "the four books of Kings" (i.e. 1 Samuel-2 Kings) because they are too warlike makes no sense; Joshua and Judges are even more warlike. Wright's suggestion, following Bradley, is that Ulfilas translated the books in the order he felt most important, and that Kings was last on his list. In any case, some of the Old Testament books seem to be translated in a style distinct from the New Testament, so there were likely multiple translators.

This may not matter much, especially for our purposes, since only fragments of the New Testament survive. (At that, they are the almost only literary remains of Gothic, a language which is long since dead.) There is every reason to believe that these, at least, are all by the same translator.

The gospels are preserved primarily in the Codex Argenteus, which is thought to be of the sixth century although there are very few datable Gothic manuscripts for paleographic comparison. (A curious manuscript in many ways; it has been conjectured, e.g., that the letters, rather than being written with a pen, were engraved or perhaps painted.) Even this manuscript has lost nearly half its pages (177 survive, out of about 330 in the original), but enough have survived to tell us that the books are in the "Western" order (Matthew, John, Luke, Mark), and that the manuscript included Mark 16:9-20 but omitted John 7:53-8:11. The image of the manuscript at right demonstrates this; the page contains John 7:52, 8:12-17.

Other than the Argenteus, all that has come to light of the gospels are a small portion of Matthew (parts of chapters 25-27) from a palimpsest and a few fragmentary verses of the Luke on a Gothic/Latin leaf, Codex Gissensis, destroyed during the Second World War. There is also a scrap of a commentary on John, from which Wright manage to produce a text of most of John 12, all of 14-15, and 17. It has been claimed that Wright's fragments are older than Argenteus, but the reliability of the dating is open to question. Among the interesting readings in those chapters of John, Wright credits it with reading "Judas son of Simon Iscariot" in 12:4. He includes 12:8 (omitted by D). It has the longer reading with "you know the way" in 14:4.

According to Metzger, nothing has survived of the Acts, Catholic Epistles, and Apocalypse. Of Paul there are several manuscripts, all fragmentary and all palimpsest; all thought to be derived from Bobbio. The only book for which we can assemble a complete text is 2 Corinthians (though the fragments of Romans, 1 Corinthians, Ephesians, and 1 and 2 Timothy are very substantial), and Hebrews is entirely lacking. It has been speculated that Ulfilas, for theological or other reasons, did not translate Hebrews, but Vincent Broman informs me that Gothic Hebrews has been quoted in a commentary. Broman also tells me that the Old Testament is almost all lost, though there is a fragment of Nehemiah large enough to indicate a Lucianic ancestor. We have a few other scraps as well, e.g. of Ezra. These are from a manuscript in the Ambrosian Library at the Vatican.

Ulfilas's version is considered literal (critics have called it "severely" literal, preserving Greek word order whether it fits Gothic or not). It is very careful in translation, striving to always use the same Gothic word for each Greek word. Even so, Gothic is a Germanic language, and so cannot distinguish many variations in the Greek (e.g. of verb tense; some word order variations are also impermissible). It is also possible, though by no means certain, that Ulfilas (who was an Arian preaching to Arians) allowed some slight theological bias to creep into his translation. Nonetheless there is some variation in translation style in the Gospels, with Matthew regarded as having a more "primitive" translation style (more literal, and with more calques) than Luke and Mark; John is somewhere in between. The obvious suggestion is that Matthew was simply the first book translated, and that Ulfilas's work became more fluid as he gained practice, but some have seen Old Latin influence in Luke and Mark; others have suggested that Luke and Mark, as we now have them, are Visigothic, Matthew and John Ostrogothic. I've even seen one suggestion that there were four stages of revision between Ulfilas's original and the most recent texts. Given the limited amount of evidence, we probably cannot hope for certainty -- since there is almost no text that exists in more than one copy, any such stages of recension are clearly hypothetical.

In the Gospels, the basic run of the text is very strongly Byzantine, although von Soden was not able to determine what subgroup it belongs with. (The other suggestions about its kinship are too methodologically poor to even bear mentioning.) Burkitt found a number of readings which the Gothic shared with the Old Latin f (10), though scholars are not agreed on the significance of this. Some believe that the Old Latin influenced the Gothic (see the note above about translation style); others believe the influence went the other way. Our best hint may come from Paul. Here the Gothic is again Byzantine, but less so, and it has a number of striking agreements with the "Western" witnesses. It has been theorized that Ulfilas worked with a Byzantine Greek text, but also made reference to an Old Latin version. Presumably this version was either more "Western" in the Epistles, or (perhaps more likely) Ulfilas made more reference to it there. This would make the Gothic, in effect, an Old Latin rather than an independent witness, but given the value of the Old Latin, this is not entirely bad.

It has also been suggested that Ambrosiaster's writings influenced the Gothic, and that there are also readings influenced by Pelagius, Augustine, and Jerome, although these presumably came later. It might be, however, that this is more the influence of an Old Latin like b or perhaps d, both close to Ambrosiaster, since others have seen a kinship to d.

It is much to be regretted that the Gothic has not been better preserved. While the Gospels text is not particularly useful, a complete copy of the Epistles might prove most informative. And it is, along with the Peshitta, one of the earliest Byzantine witnesses; it might provide interesting insights into the Byzantine text.

The handful of survivals are also of keen interest to linguists, as the Gothic is the earliest known member of the Germanic family of languages, predating the earliest Old English texts by a couple of centuries; it is also of significance as the only attested East Germanic language (the Germanic group is thought to have three families: The West Germanic, which includes all languages now called "German," plus English, Dutch, Frisian, and Yiddish; the North Germanic, which gave rise to Icelandic, Faroese, Swedish, Danish, and Norwegian, which are still mostly mutually intelligible and amount to hardly more than a single source; and the East Germanic, which consists solely of Gothic). Thus the Gothic is very important in reconstructing proto-Germanic -- and, indeed, Indo-European.

Personally, I am surprised there aren't more Gothic scholars among textual critics. Based on the samples in Joseph Wright's Grammar of the Gothic Language (which contains a complete copy of Mark in Gothic, with a Greek parallel of several chapters, plus 2 Timothy and some other selections), Gothic appears quite easy for a modern English speaker to learn, especially one who has some Greek.

The alphabet is a modified Greek alphabet with a runic sort of look; the table below shows the actual Gothic if you have the right unicode fonts and approximates it in more common characters if you don't:

| True Gothic | 𐌰 | 𐌱 | 𐌲 | 𐌳 | 𐌴 | 𐌵 | 𐌶 | 𐌷 | 𐌸 | 𐌹 | 𐌺 | 𐌻 | 𐌼 | 𐌽 | 𐌾 | 𐌿 | 𐍀 | 𐍂 | 𐍃 | 𐍄 | 𐍅 | 𐍆 | 𐍇 | 𐍈 | 𐍉 |

| Looks (a little) like | ᵔA | B | Γ | Δ | ϵ | u | z | h | ψ | ï | K | Λ | M | N | G | n | Π | R | S | T | Y | F | X | Θ | ᴥ |

| phonetic | a | b | g | d | e | q | z | h | þ | i | k | l | m | n | j | u | p | r | s | t | w | f | χ | ƕ | o |

To demonstrate the point about the ease of understanding Gothic once you can read the alphabet, consider, e.g., the first two verses of Mark in phonetic form:

(1) Anastōdeins aíwaggēljōns Iēsuis Xristáus sunáus guþs. (2) Swē gamēliþs ist in Ēsaïsin praúfētáu: sái, ik insandja aggilu mainana faúra þus, saei gamanweiþ wig þeinana faúra þus.

Incidentally, although this version seems always to be called the "Gothic," Glanville Price, Encyclopdia of the Languages of Europe, 200, p. 210, says that the translation is Visigothic -- but the manuscript copies are from Ostrogothic areas. This makes it likely that there have been some errors in, or adjustments to, or variations in, the spelling as Ostrogothic scribes tried to deal with the Visigothic dialect.

Latin

Bonifatius Fischer's Vetus Latina Institute, now more than a half a century old, has done tremendous work on both the Old Latin and Vulgate translations of the Bible. Their publications have made a vast amount of data available. But, ironically, they have not produced a good general introduction to the Latin versions. What follows cannot substitute for that, especially since I do not have access to all the VLI publications. But it attempts to give a general overview.

Of all the versions, none has as complicated a history as the Latin. There are many reasons for this, the foremost being its widespread use. The Latin Vulgate was, for more than a millenium, the Bible of the western church, and after the fall of Constantinople it was the preeminent Bible of Christendom. There are at least eight thousand Latin Bible manuscripts known -- or at least two thousand more Latin than Greek manuscripts.

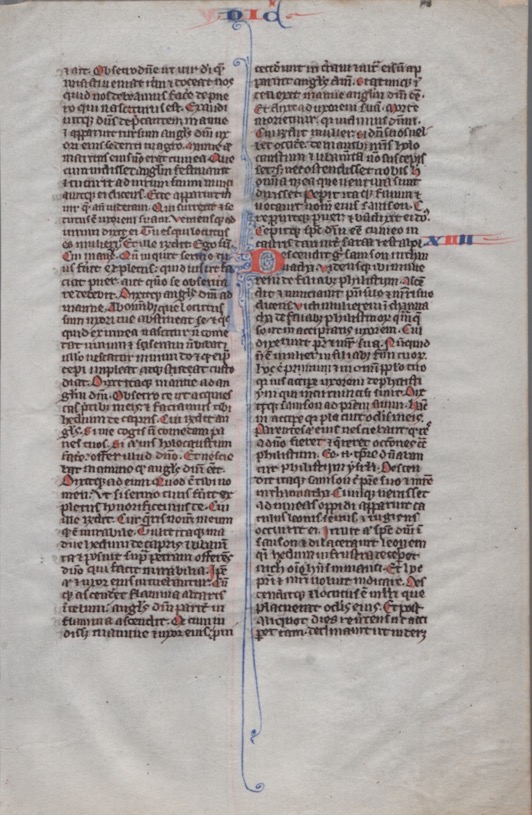

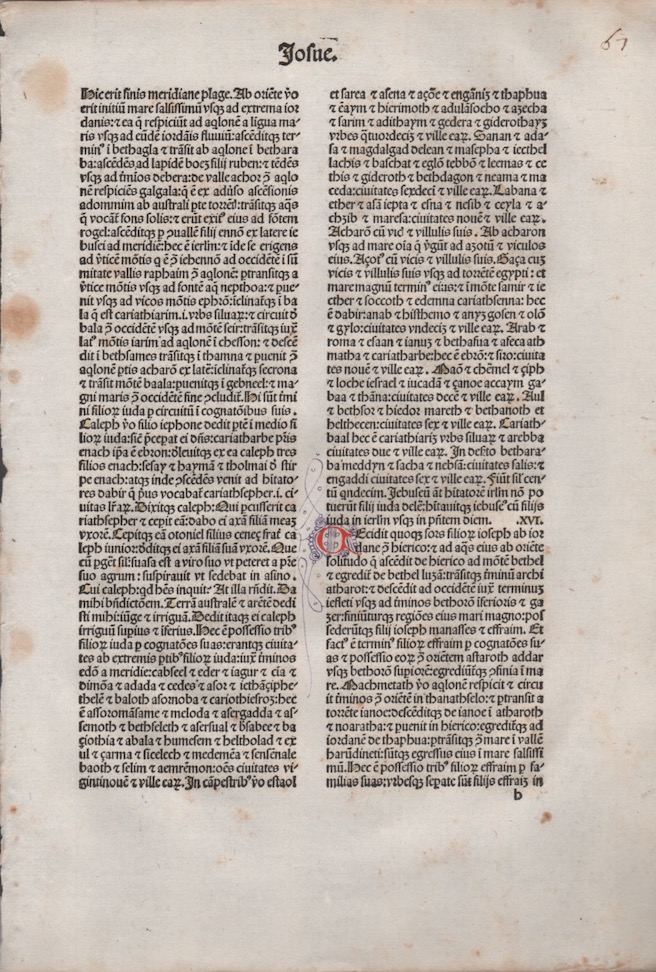

| The first reference to what appears to be a Latin version dates from 180 C.E. In the Acts of the Scillitan Martyrs, one of the men on trial admits to having writings of Paul in his possession. Given the background, it is presumed that these were in a Latin version. | Below: An Old Latin manuscript, Codex Sarzensis (j), on purple parchment, much damaged by the gold ink used to write it. Shown in exaggerated color |

But which Latin version? That is indeed the problem -- for, in the period before the Vulgate, there were dozens, perhaps hundreds. Jerome, in his preface to the Vulgate gospels, commented that there were "as many [translations] as there are manuscripts." Augustine complained that anyone who had the slightest hint of Greek and Latin might undertake a translation. They seem to have been right; of our dozens of non-Vulgate Latin manuscripts, no two seem to represent exactly the same translation.

Modern scholars have christened these pre-Vulgate translations, which generally originated in the second through fourth centuries, the "Old Latin." (These versions are sometimes called the "Itala," but this term is quite properly going out of use. It arose from a statement of Augustine's that the Itala was the best of the Latin versions -- but we no longer believe we know what this statement means or which version(s) it refers to.)

The Old Latin gospels generally, although by no means universally, have the books in the "Western" order (Matthew, John, Luke, Mark) -- an order found also in D and W (as well as in the Gothic version) but otherwise very rare among Greek manuscripts.