Non-Biblical Textual Criticism

Contents: Introduction * The Methods of Classical Criticism: Recensio, Selectio, Examinatio, Emendatio * Books Preserved in One Manuscript * Books Preserved in Multiple Manuscripts * Books Preserved in Hundreds of Manuscripts * Books Preserved in Multiple Editions * Textual Criticism of Lost Books * Other differences between Classical and New Testament Criticism * Appendix I: Textual Criticism of Modern Authors * Appendix II: History of Other Literary Traditions * Appendix III: The Bédier Problem

Introduction

Textual criticism does not apply only to the New Testament. Indeed, most aspects of modern textual criticism originated in the study of non-Biblical texts. Yet non-Biblical textual criticism shows notable differences from the New Testament variety. Given the complexity of the field, we can only touch on a few aspects of non-Biblical TC. But I'll try to summarize both the chief similarities and the major differences.

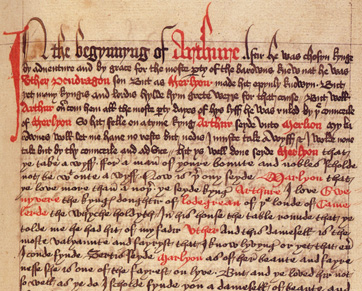

In one sense, the materials of secular textual criticism resemble those for Biblical criticism. Both are involved with manuscripts other than the autograph -- or, in a few strange cases such as Malory's Morte D'Arthur and the works of Shakespeare, with the relationship between editions and autographs. (We have only two early sources for Malory, both near-contemporary: Caxton's printed edition and a manuscript presumably close to the autograph. They differ recensionally at some points: Caxton evidently rewrote.) The works of Sir Walter Scott are an even more complex case: Scott's native language was Braid Scots; it differs in pronunciation and vocabulary, though hardly in grammar, from British English, which is the language in which his books were to be published. To a significant extent, he relied upon his publisher to correct his Scotticisms. He also produced a second edition of many of his works, making marginal emendations in the first edition. So what is the authoritative text of, say, Ivanhoe -- Scott's manuscript, Scott's first edition, Scott's interlinear folios which were the source for the second edition, or the second edition? And how do Scott's corrections to the galley proofs fit into this? Not all of his corrections were proper English, and the editors ignored some of these. Thomas Percy's Reliques have some similar problems, because there quite literally was no original manuscript. Percy assembled fragments from various sheets he had collected, tore out portions of manuscripts (yes, the man was a vandal), scribbled over it them, promised fillers but supplied them late, added material after portions of the book had been printed, and in general did everything he could to torture his poor printer. Little wonder that the book took two and a half years to publish. But what, then, is "the" text of the Reliques? The various materials Percy submitted? The corrected proofs? Something else? This is a book which was published in relatively modern times by a known author, but still there is no autograph. | The sole manuscript of Malory, British

Library Add. 59678. The top portion of folio 35, showing the change from

the first hand to the second (a change which seems to prove that it is not

the autograph). The manuscript is imperfect; eight leaves are lost at the

beginning, and probably as many at the end.

This manuscript seems to have been known to Caxton; there are

marks from his print shop in it. But the published edition differs, sometimes

dramatically, from the manuscript. It appears that Caxton rewote most extensively in the earlier portions, where Malory was, in effect, writing independent short stories; the end, in which Malory seems to be trying to create a unified narrative, is almost the same in manuscript and print book. The whole still poses an interesting challenge to textual critics, since the manuscript is not the autograph and there are hints that Caxton had some other source -- perhaps another manuscript. Copies of Caxton's first printed edition are almost as rare as manuscripts: Only two survive, and one of them imperfect. Simply being printed did not assure the survival of documents! |

The history of printed editions of classical works is often similar to that of the New Testament text following Erasmus: "[T]he early printers, by the act of putting a text into print, tended to give that form of the text an authority and a permanence which in fact it rarely deserved. The editio princeps of a classical author was usually little more than a transcript of whatever humanist manuscript the printer chose to use as his copy.... The repetition of this text... soon led to the establishment of a vulgate text... and conservatism made it difficult to discard in favour of a radically new text" (L. D. Reynolds & N. G. Wilson, Scribes & Scholars, second edition, 1974, p. 187).

There is, however, one fundamental difference between classical and Biblical textual criticism. Without exception, the number of manuscripts of classical works is smaller. Even the Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine, which in many countries was better-known than the Bible itself, exists in only about a thousand copies. The most popular classical work is the Iliad, represented by somewhat less than 700 manuscripts (though these manuscripts actually average rather older than New Testament manuscripts. Papyrus copies of Homer are numerous. As early as 1920, when the New Testament was known in only a few dozen of papyrus copies, there were in excess of a hundred papyrus texts of the Iliad known, a fair number of which dated from the first century C. E. or earlier.) But the case of Homer is hardly normal. More typical are works such as Chaucer (somewhat over 80 manuscripts of the Canterbury Tales, of which about two-thirds once contained the complete Tales; a few dozen copies of most of his other works). From this we work down through Piers Plowman (about forty manuscripts) to Thucydides, preserved in only eight manuscripts (this even though he was so well-known and admired that one of Josephus's assistants is known as the "Thucydidean hack") to the literally thousands of works preserved in only one manuscript -- including such great classics as Beowulf, the Norse myths of the Regius Codex, Tacitus (Tacitus's Annals are preserved in two copies, but as the copies are partial and do not overlap at all, for any given passage there is only one manuscript). Indeed, there are instances where all manuscripts are lost and we must reconstruct the work from excerpts (Manetho; the non-Homeric portions of the Epic Cycle; most of Polybius, etc.)

This produces a problem completely opposite that in New Testament TC. In New Testament TC, we can usually assume that the original reading is preserved somewhere; the problem is one of sorting through the immense richness of the tradition to find it. In classical criticism, the reverse is often the case: We know every manuscript and every reading in the tradition, but have no assurance that the tradition preserve the original reading. As an example, consider a reading from Gregory of Tours' History of Tours: in I.9 the manuscripts of Gregory allude to the twelve patriarchs (specifically mentioning that there are twelve) -- and then list only nine: Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Zebulun, Dan, Gad, Asher. Clearly, three names -- Naphtali, Benjamin, and either Joseph or his sons -- have been omitted. But where in the reading? And is it Joseph, or his sons? We simply cannot tell.

It will be observed that many of the documents cited above are in languages other than Greek. Textual criticism, of course, can be applied in all languages; the basic rules are the same (except for those pertaining to paleography and other aspects related to letter forms and the history of the written language). For perspective, many of our examples will be based on works written in languages other than Greek -- though, because I lack the background, none will be taken from ideographic languages.

The text which follows is littered with footnotes and parentheses. I am genuinely sorry about this, since it makes the article much more confusing. But this is a far more complex field than New Testament criticism -- there are many different sorts of documents requiring many different techniques. Most rules have long lists of exceptions. And I don't want to deceive by overgeneralizing. The only alternative is the long list of special cases.

The Method of Classical Textual Criticism

Classical textual criticism, as its name implies, goes back to the classical Greeks, who were concerned with preserving the text of such ancient works as Homer. One of the centers of ancient textual criticism was Alexandria; it has been theorized (though there is no evidence of this) that the reason for the relative purity of the Alexandrian text of the New Testament is that Egyptian scribes were influenced by the careful and conservative work of the Alexandrian school. Their textual work on Homer was not always sophisticated (indeed, their conclusions were often quite silly), but they developed a critical apparatus of high sophistication (see the discussion of Alexandrian Critical Symbols).

Modern textual criticism, however, dates back to Karl Lachmann, who would later edit the first text of the New Testament to be fully independent of the Textus Receptus. In his work on Lucretius, Lachmann defined the basic method that has been used ever since.

It is interesting to note that, while New Testament textual critics break themselves down into two groups, textual critics of vernacular works see three classes (see compare Ralph Hanna III, "(The) Editing (of) The Ellesmere Text," in Martin Stevens & Daniel Woodward, editors, The Ellesmere Chaucer: Essays in Interpretation, Huntington Linrary & Yushodo Co., Ltd., 1997, pp. 225-226). The three are Best Text editors, who largely follow the lead of Bédier and print the text of a single source almost unaltered; Eclectics, who choose between texts based on their own interpretation of the best reading; and stemmatic workers. Westcott and Hort are sometimes regarded as Best Text editors (although they were in fact more eclectic than any Best Text editor I've ever studied); Lachmann invented the stemmatic method but was unable to use it on the New Testament; every other New Testament critic since then has been some type of eclectic.

I, on the other hand, would at least like to be able to work stemmatically. So here is an outline of how it is done.

Textual criticism, in this system, proceeds through four basic steps (some of which will be neglected in certain cases, and which occasionally go by other names):

- recensio, the creation of a family tree for the manuscripts of the work

- selectio, the comparison of the readings of the various family members, and the determination of the oldest reading (this is sometimes considered to be part of recensio)

- examinatio, the study of the resultant text to look for primitive errors

- emendatio, (also called divinatio, and sometimes considered to be a part of examinatio or vice versa), the correction of the primitive errors.

Recensio

Recensio is the process of grouping the manuscripts into a stemma or family tree. Of all the steps involved in classical textual criticism, this is the one regarded as having the least direct relevance for New Testament TC. In this stage, the differences between the manuscripts are compared and a stemma compiled. (This assumes, of course, that several manuscripts exist. If there is only one manuscript, we will omit this stage, as described in the section on books preserved in one manuscript.)

The essential purpose of the stemma is to lighten our workload, and also to tell us what weight to give to which manuscripts. Let's take an example from Wulfstan's thirteenth homily (a pastoral letter in Anglo-Saxon). Five manuscripts exist, designated B C E K M, the latter being fragmentary. According to Dorothy Bethurum, these manuscripts form a stemma as follows (with lost manuscripts shown in [ ] -- a useful convention though not one widely adopted):

[ARCHETYPE]

|

-----------

| |

[X] [Y]

| |

----- |

| | |

C E B

|

[Z]

|

-----

| |

K M

That is, the archetype gave rise to two manuscripts, X and Y, now both lost. (Based on the stemma itself, it would appear that the archetype was actually the parent of X and Y, but this is by no means certain in reality.) B was copied from Y, and C and E were copied from X. Another lost manuscript, Z, was copied from C, and gave rise to K and M.

Observe what this tells us. First, K and M are direct descendents (according to Bethurum, anyway) of C. Therefore, they tell us nothing we don't already know, and can be ignored. Second, although C, E, and B are all primary witnesses, they don't have the same weight. Since C and E go back to a common archetype [X], their combined evidence is no greater than B alone, which goes back to a separate archetype. (We might find that [X] was a better witness than [Y], but the point is that C and E are dependent and B is independent. That is, the combination B-C against E is a good one, and B-E against C is good, but C-E against B is inherently weaker; it's ultimately a case of one witness against another.)

We also know that K and M have no value at all; their readings all go back to C, and since we have C, we have no need to consult K and M (unless C is incomplete, but that does not apply in this case). Such manuscripts are said to be eliminated from consideration (the process of so doing being called eliminatio.)

So how does one determine a stemma?

One begins, naturally, by collating the manuscripts (in full if possible, though family trees are sometimes based on samples). This generally requires that a single manuscript be selected as a collation base. (Unfortunately, since the manuscripts are not yet compared, the manuscript to collate against must be chosen unscientifically. One may choose to start with the oldest manuscript, or the most complete, or the one most superficially free of scribal errors; as Charles Moorman comments on page 35 of Editing the Middle English Manuscript, the determination can only be made "by guess or God." Fortunately, while choosing the right collation base makes everything easier, using the wrong base should not affect the result.)

Once the manuscripts are collated, one proceeds to determine the stemma. Methods for making this determination vary. Lachmann based his work on "agreement in error." This is a quick and efficient method, but it has two severe drawbacks: First, it assumes that we know the original reading (never a wise assumption, although critics as recent as Zuntz have sometimes used this technique), and second, it requires a fairly close-knit manuscript tradition. Both criteria were met by Lucretius, the author Lachmann studied.

According to the latest research I have seen (summarized on pp. liv-lvii of the Loeb Classical Library edition of Lucretius, the 1992 revised edition by Martin Ferguson Smith), the stemma of the Lucretius is as follows:

AUTOGRAPH

|

ARCHETYPE (with 26 lines per page)

|

---------------------

| |

O (?)

(IX; corrected |

by Dungal) ------------

| | |

(Poggio's MS) Q G+U+V

| (IX) (IX)

-------------

| |

L Other MSS (about 50, from Italy; XV-XVI)

This stemma, being so compact, is readily revealed by agreement in error. Other books are not as cooperative. Paul Maas observed that the agreement-in-error method requires two presuppositions: "(1) that the copies made since the primary split in the tradition each represent one exemplar only, i.e. that no scribe has combined several exemplars (contaminatio), (2) that each scribe consciously or unconsciously deviates from his exemplar, i.e. makes peculiar errors" (Paul Mass, Textual Criticism, translated by B. Flowers, p. 3). The first of these conditions will generally be true for obscure writings -- but it is no more true of the Iliad or the Aeneid than it is of the New Testament. As for the latter requirement, it makes scribes into badly-programmed computers -- they are not accurate, but are inaccurate in particular and repeatable ways. This can hardly be relied upon.

In addition, there is an unrecognized assumption in Maas's Point 1: That there is a "primary split" -- i.e. that the text falls into two and only two basic families. Bédier noted that the "agreement in error" method seems always to lead to trees with two and only two branches. (This is not as surprising as it sounds. First, it should be noted that most variants have two and only two readings. Thus a single point of variation can only identify two types. On this basis, if there are more than two types, the types which are more closely related, or merely more similar, will tend to be grouped as a single text-type. Thus when trying to seek new text-types, the first place to look is probably in the largest and most diverse of the established types. This is certainly true in the New Testament; the "Western" text has generally defied attempts to subdivide it, but the Alexandrian text often can be subdivided -- in Paul, for instance, the manuscripts called Alexandrian actually fall into three groups: 𝔓46+B, Family 1739, and ℵ+A+C+33+81+1175+al. For fuller discussion, see the appendix on The Bédier Problem.)

The good news is, if we do somehow construct a stemma with more than two branches, things are easy from there: majority rules, and Maas says, "where the primary split is into at least three branches, [it is possible] to reconstruct with certainty the text of the archetype in all places (with a few exceptions to be accounted for separately)."

|

In any case, for most sorts of literature we cannot identify errors with the certainty that Lachmann could. As Moorman notes (p. 50), "For what passes in recension as science is in fact art and as such depends for its success upon the artistry of the editor rather than the accuracy of the method." E. Talbot Donaldson makes this point even more cogently in "The Psychology of Editors of Middle English Texts": "It is always carefully pointed out that MSS may be grouped together only on the basis of shared error, but it is seldom pointed out that if an editor has to be able to distinguish right readings from wrong in order to evolve a stemma which will in turn distinguish right readings from wrong for him, then he might as well go on using this God-given power to distinguish right from wrong throughout the whole editorial process, and eliminate the stemma. The only reason for not doing so is to eliminate the appearance -- not the fact -- of subjectivity: the fact remains that the whole classification depends on purely subjective choices made before the work of editing begins." The student, therefore, who wishes to have a truly repeatable method and must be content to work from agreements in readings (which is slower but does not depend on any assumptions). This, if pursued consistently, is a more than adequate method (and it can be made to work even if our manuscripts are mixed, as Lachmann's were not). It can also, if a system of characteristic readings is used, identify multiple independent branches of the tree, even if two branches are more similar to each other than to a third branch. | Below:

Perhaps the single most important manuscript of Wulfstan: Cotton Nero A I,

bearing corrections perhaps by Wulfstan himself. This is the introduction

to Homily XX, the Sermon to the English. Observe the Latin introduction --

and how distinct are the alphabets used for the Latin and the Old English!

The Latin preface reads (abbreviations expanded; note the interesting use of the chi-rho for "per"): SERMO LUPI AD ANGLOS QUANDO DANI MAXIME PERSECUTI SUNT EOS, QUOD FUIT ANNO MILLESIMO .XIIII, AB INCARNATIONE DOMINE NOSTRI IESU CRISTI The five complete lines of the Old English text shown here are Leofan men, gecnawað þæt soð is: ðeos worold is on ofste, 7 hit nealæcð þam ende, 7 þy hit is, on worolde aa swa leng swa wyrse; 7 swa hit sceal nyde for folces synnan, ær antecristes tocyme, yfelian swyþe, 7 huru hit wyrð þænne |

(Note: There are cases where agreement in error is absolutely reliable. A classic instance is in Arrian. Here, one codex is missing a leaf, causing a lacuna. Every other known copy -- there are about forty -- proceeds from the last word on the page before the loss to the first word of the page after, with no indication of anything missing. Thus, one can be sure that all the manuscripts are descended from this one -- and that it lost the leaf before the others were copied. Observe that this is identical to the situation of Fp and Gp, which also have lacunae in common.)

(Additional note: It appears that this method has now been rendered truly reliable. Stephen C. Carlson's work on Cladistics seems at last to have rendered stemmatics mathematically coherent and repeatable.)

This is not entirely to dismiss agreements in error even in the New Testament tradition. I use agreements in error regularly in grouping Byzantine manuscripts. For closely-related texts such as those, it is a completely reliable method. The problem comes in when one moves away from the closely-related texts. Zuntz, for instance, classed 𝔓46, B, and 1739 together based on what he considered shared errors. But looking at overall agreements makes this appear quite wrong: 𝔓46/B and 1739 are separate types, and Zuntz's shared errors in fact give every evidence of being the original text!

It's worth stressing that there are instances where scholars have created inaccurate stemma by the above means. The Middle English work Pierce the Ploughman's Creed (Piers Plowman's Creed) exists in three substantial copies. W. W. Skeat thought all three to be derived from the same original. A. I. Doyle offered strong evidence that this is not so. An even more absurd situation occurs in the homilies of Wulfstan. There are four extant manuscripts of Homily Xc: C E I and B. N. R. Ker suggested that I contained marginalia in the hand of Wulfstan himself, and Dorothy Bethurum concedes that it offers "a more authoritative text of the homilies it contains than do any of the other manuscripts" -- yet she offers this stemma, which puts I and its marginalia at the end of the copying process:

[Archetype]

|

-----------------

| |

[X] [Y] <-- lost heads of manuscript families

| |

--------- ------

| | \ | |

C E \ I* B

\ /

\ /

I**

A possible stemma, certainly, but what are the odds that Wulfstan would work on a third generation manuscript instead of a first or second generation copy?

Even if documents do descend from the same original, it cannot automatically be assumed that they are sisters as opposed to cousins at some remove. If manuscripts are sisters, then every deviation, be it as small as a change in orthography, must be explained. These requirements are much less strict for cousins, since there could have been work done on the intervening copies. It is much easier (and probably more accurate!) to produce a sketch-stemma than a detailed stemma -- and there is really no loss. If you know which manuscripts are descended from others, no matter at how many removes, the primary purpose of recensio has been served. (And it's worth noting that sketch stemma are possible even for New Testament manuscript groupings such as Family 2138.)

Sometimes it will be found that recensio brings us back to a single surviving manuscript. For example, it is believed that all Greek manuscripts of Josephus's Against Apion are derived from the imperfect Codex Laurentianus (L) of the eleventh century. In this case we are, in effect, in the situation of having only one manuscript (or, in the case of Against Apion, one manuscript plus a Latin translation and extensive quotations from Eusebius, the latter two being the only authorities for a large lacuna in L and all its descendants). We proceed to the final stages (examinatio and emendatio) as described below.

(We should add a few footnotes to the above statement about it not mattering if there are intermediate generations between ancestor and descendant manuscripts; the statement is absolutely true only if the archetype manuscript is complete and entirely legible, and if all the descendents are immediate copies. If, for instance, the exemplar is damaged, even for just a few letters, we may need to turn to the copies to reconstruct it. This happens in the New Testament, e.g., with Codex Claromontanus and its copies. D/06 has lost its first few verses, and we use Dabs1 -- which has no other value -- to reconstruct them. Also, if manuscript B is not a daughter of manuscript A, but rather a granddaughter or later descendent, it may have picked up a handful of reading from mixture in the intervening steps. Although most places where B differs from A can be ignored as scribal errors, it is not proper to dismiss them entirely out of hand. Similarly, there may be marginal scholia in B which come from a different source, and may inform us of other readings.)

While some traditions will resolve down to a single surviving archetype, it is also common to find that all the manuscripts prove to derive from a lost archetype which is not the autograph. This is the case, for instance, with Æschylus. We have dozens of manuscripts all told (in fact, the number approaches one hundred) -- but they all contain the same seven plays or a subset. It appears that every extant manuscript derives its contents from a single manuscript of about the second century, which contained these seven and no others. (The later copies may include a few readings derived from other ancient manuscripts, but the plays they contain are based on that one manuscript.)

To critics accustomed to the riches of the New Testament, this may seem highly unlikely. But we should recall that most classical texts, including Æschylus and the other Greek dramatists, were the sole preserve of the educated -- used only in the schools to teach Attic grammar and the like (even a relatively small book cost the equivalent of a month's wage for a civil servant, and could be more; the tenth century Archbishop Arethas's copy of Plato cost 21 gold pieces when the annual salary was 72). In a number of cases of classical works, it is theorized that the ancestor of all copies was a lone uncial. In the ninth or tenth century, perhaps as a result of Photius's revival of learning, this uncial was transcribed into minuscule script. Since this transcription took real effort (the scribe had to determine accents, word divisions, etc.), all later copies would be derived from this one ninth century minuscule transcript. The only way multiple families would emerge is if two different schools transcribed their uncials. (Or, of course, if the text evolved after the ninth century, but given the limited number of copies made in that time, when the Byzantine Empire was much reduced and under severe stress, this seems relatively unlikely.) Even if other copies existed in Byzantine libraries, vast numbers were destroyed in the sacks of Constantinople in 1204 and 1453. (It is believed, in fact, that the Christian Crusaders who sacked Byzantium are more at fault than the Ottoman Turks who finally captured Constantinople in 1453. The Crusaders had no use for literature, while the Ottomans respected learning. In addition, real efforts were made to rescue surviving literature after 1204. So if an author's work was not made accessible in the years after 1204, it is probably because all copies had been destroyed by then.) Therefore, when confronted with a single lost manuscript, we reconstruct that archetype and then proceed to examinatio and emendatio.

But for documents which were widely copied (even if only a limited number of copies survive), we usually find more complex traditions, such as those shown here for Seneca's tragedies and Xenophon's Cyropædia. In these instances, there were a handful of early copies which spawned families of related manuscripts.

In these charts, extant manuscripts are shown in plain type and lost, hypothetical manuscripts are shown in [brackets]. Fragments are marked %.

[Seneca's Autograph]

|

------------------

| |

[E-Group] [A-Group]

| |

------------- -----------

| | | | | |

E R% T% α ψ A1

|

[Σ]

|

-----

| |

M N

[Xenophon's Autograph]

|

----------------------------------------------

| | | | | |

[x] [y] [z] | | |

| | | | | |

----- ----- --------- | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

C E D F A G H r% m% π2%

This situation also occurs in New Testament manuscript families. (So there is actually some relevance to this.) For example, Von Soden's breakdown of Family 13 would produce a stemma like this (note that other scholars have given somewhat different, and perhaps more accurate, stemma):

[Φ]

|

----------------------------------------------------

| | | |

[w] [x] [y] [z]

| | | |

----------- ------- --------------------- |

| | | | | | | | | | |

13 788 69 1689 983 826 543 346 230 828 124

It should be noted that stemma are not always this simple; families may have sub-families. Rzach, for instance, found two families in Hesiod's Theogony, which he labelled Ψ and Ω. But Ω, which consisted of seven manuscripts (to two for Ψ), had three subgroups, Ωa, Ωb, and Ωc.

This reminds us of Bédier's warning about finding only two branches, and also about making casual assumptions about the relationships of the groups. In the Theogony, can we be sure that the two manuscripts of Ψ actually form a group, or are they simply non-Ω manuscripts? (This problem is well known in other contexts: It's called "long branch assimilation," where two specimens far from the main mass appear to converge simply because they're so different.) Do the three subgroups of Ω actually form a larger group, or are they simply closer to each other than to Ψ? There is no assured answer to any of these questions, but it reminds us that we must be careful in constructing our stemma. One should also be aware that new discoveries can affect the stemma. (This, in fact, can apply also in NT TC; the discoveries of 𝔓46, 𝔓47, and 𝔓75 have all given us reason to re-examine the textual picture of the books they contain.)

Having determined the families, their nature must be assessed. This process has analogies in New Testament criticism (consider Hort's analysis of the "Western" and Alexandrian/"Neutral" types), except that in classical criticism it usually applies to precisely defined texts as opposed to Hort's less-well-defined text-types. (The difference being that the reading of a text, being derived from a single ancestor, can in theory be determined exactly; text-types properly speaking will not have a single ancestor, and so no pure original can be reconstructed. Text-types are a collection of similar manuscripts.)

Once the types have been assessed, it may prove that one or another group is so corrupt as to offer little more than a source of possible emendations. (This is almost the case with the families of Seneca shown above: The E text is regarded as clearly superior, so much so that A-group readings are rarely considered if the E group makes sense. This rule is also often applied, though unjustifiably, in Old Testament criticism, where the LXX usually is not even consulted unless the Masoretic Text appears defective.) But this situation where one particular family is universally superior is not usual; more often we find that each group has something to contribute -- though we may also find that different groups have different sorts of faults (e.g. one may be prone to omission, one to paraphrase, and another to errors of sight).

Once we have assessed the types, we proceed to the next step in the process....

Selectio

This phase of the critical process occurs only if recensio reveals two or more textual groupings more recent than the autograph. If we have only one manuscript, or if our manuscripts all go back to a single ancestor, selectio has no role to play. For selectio consists of choosing the most primitive of the surviving variants.

When we begin this process, we know our materials. Manuscripts have been grouped, their local archetypes more or less reconstructed, and their variants known. Now we must proceed to assess and choose between the variants.

Here one applies canons of criticism generally similar to those applied to the New Testament, though there are exceptions. So, for instance, we still accept the rule "that reading is best which best explains the others." And obviously the same basic scribal errors (homoioteleuton, etc.) still occur. But in secular works, one is unlikely to see the piling on of divine titles one often observes in the Bible (so, e.g., if a Greek author refers to "the Lord," it is hardly likely that a scribe will expand it to read "the Lord Jesus Christ"). Similarly, there is little likelihood of assimilation to remote parallels such as we find in the Gospels and Colossians (although assimilation to local parallels can and does occur). And, of course, there is no Byzantine text to influence the tradition (though there may, in some limited instances, be some equivalent sort of majority text that affects other manuscripts).

For all that we apply canons of criticism here, the usual approach is a sort of "modified majority" process (rather like the American electoral system, in which each congressperson is elected by a majority in that person's district, and laws are passed by a majority of those congressmen -- meaning that a law can actually be passed despite being opposed by the majority of the general electorate). Consider the following provisional stemma of nine manuscripts M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U. The manuscripts A (the archetype), B, C, D, and E are all hypothetical (indicated by square brackets about the letters).

[A]

|

--------------------------

| |

[B] [E]

| |

----------- |

| | |

[C] [D] |

| | |

----- ----- -----------------

| | | | | | | | |

M N O P Q R S T U

Now suppose we have two readings, X and Y. Assume these two are equally probable on internal grounds. Assume that X is read by M, N, P, and R, while O, Q, S, T, and U have reading Y. Thus, Y is the majority reading. However, reconstruction indicates that X is actually the correct reading. How do we determine this? We follow these steps:

- Observe that M and N agree (this is the only subgroup where all the manuscripts agree). Therefore C had reading X, since this is supported by both M and N.

- Observe that C agrees with one of the manuscripts of the D group (in this case, P). This implies that the original reading of D was X, in agreement with C, and that the reading of B was therefore X

- Observe that B agrees with one of the manuscripts of the E group (in this case, R). This implies that the original reading of E was X, and that the reading of A was therefore X.

The above is not absolutely certain, of course. If reading X could have arisen as an easy error for Y, then Y might be original. Or there might be mixture -- the eternal bugaboo of critics -- involved. Intelligence and critical rules must be applied. But the above shows how a text can be reconstructed where critical rules are not clear. Whatever rule we use for a particular reading, we eventually reconstruct the set of readings we believe to have existed in the archetype.

When this is done, we have achieved a provisional text -- the earliest text obtainable directly from the manuscripts. It is at this point that Biblical and classical textual criticism finally part ways. As far as Biblical TC is concerned, this is usually the last step -- though Michael Holmes has argued ("Reasoned Eclecticism in New Testament Textual Criticism," published in Bart D. Ehrman & Michael W. Holmes, editors, The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research, p. 347), that there is no fundamental reason why New Testament criticism must stop here. The general opinion of New Testament critics was expressed by Kirsopp Lake in this way (The Text of the New Testament, sixth edition revised by Silva New, pp. 8-9): "In classical textual criticism, the archetype of all the extant MSS. is often obtainable with comparatively little work, but often is very corrupt. There is therefore scope for much conjectural emendation. In Biblical textual criticism, on the other hand, it is still doubtful what is the archetype of the existing manuscripts. But at least we may be sure that it is an exceedingly early one, with very few corruptions, and therefore the work of conjectural emendation is very light, rarely necessary[,] and scarcely ever possible.")

Thus it is only in classical criticism that we proceed to...

Examinatio

This process consists, simply put, of scanning the text for errors. This step, though it may be distasteful, and certainly difficult, is necessary. Classical manuscripts were no freer of errors than were Biblical manuscripts, and are often further removed from the archetype, meaning that there have been more generations for errors to arise. So the scholar, armed with knowledge of the language and (if possible) of the style of the writer, sets out to look for corruptions in the text. If they are found, the editor proceeds to...

Emendatio

If examinatio consists of looking for errors, emendatio (also known as divinatio) consists of fixing them. This, obviously, requires the use of conjectural emendation. This is no trivial task! Take the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf as an example. The Chickering text (Howell D. Chickering, Jr., Beowulf, Anchor, 1997) includes about 280 readings not in the manuscript (of which some 200 are conjectural emendations), and other editors have proposed many emendations not adopted by Chickering. The case of the Old English poem "The Seafarer" is even worse: in 124 lines of four to ten words each (usually toward the lower end of that range), the edition of I. L. Gordon adopts 22 emendations (I. L. Gordon, The Seafarer, Methuen's Old English Library, 1960). Thus the effort involved in correcting these texts can often be greater than that of simply comparing manuscripts.

One will sometimes see the final stage, of constituting or seeking for the original text, referred to as constitutio.

Of course, the way one proceeds through the four steps of classical criticism depends very much upon the actual materials preserved. We say, for instance, that emendatio is the final step in the process. But it should use the results of the other steps. The variants at a particular point, for instance, may give a clue as to what was the original reading. If, for example, we were to find two variants, "He went to bet" and "He went too bad," a very strong conjecture would be that the original was "He went to bed." Therefore we must perform each step based on the materials available. Nor is emendation a trivial task. To repair a damaged text requires deep understanding of the language and the author's use of it (a better understanding than is required simply to read the text; when reading, you can look up a word you don't know. How can you look up a word which may not even exist?). It also requires great creativity -- and knowledge of all the materials available. The following sections outline various scenarios and how critics proceed in each case.

It is perhaps worth noting that not all textual critics have been equally skilled in all of these areas. A good example is J. R. R. Tolkien in his role as a professor of philology, in which he edited several texts. His work on Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which existed in only one manuscript, was considered excellent; there was literally no one in the world who understood the Gawain-poet's dialect and viewpoint better than Tolkien, so he was able to edit the text with an insight no one else could match. But when he set to work on Chaucer's "Reeve's Tale," he turned into the most radical of radical eclectics, basically ignoring manuscript relationships and adopting any reading he could find that conformed to his notions of fourteenth century dialects, and even occasionally emending when he didn't see the reading he thought correct. Having many manuscripts did't bring him closer to the original text; in effect, it gave him more chances to fiddle with it. On the other hand, Manley and Rickert, who are the only editors to have tried to truly classify the dozens of manuscripts of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, spent so much effort classifying manuscripts that their text was perhaps not as well-considered as it should have been. Thus, although the tendency historically has been to have one person edit a text, a strong case could be made, when there are many manuscripts, for having two, or even three, editors of a text, one in primary charge of recensio and selectio and one primarily responsible for examinatio and emendatio. If there are three, one might even split recensio and selectio, with a good solid mathematician type in charge of recensio, a true linguist in charge of examinatio and emendatio, and someone with intermediate skills in charge of selectio.

Books Preserved in One Manuscript

In terms of steps required, this is the easiest of the various sorts of criticism. There is no need for recensio or selectio. One can proceed immediately to examinatio and emendatio.

|

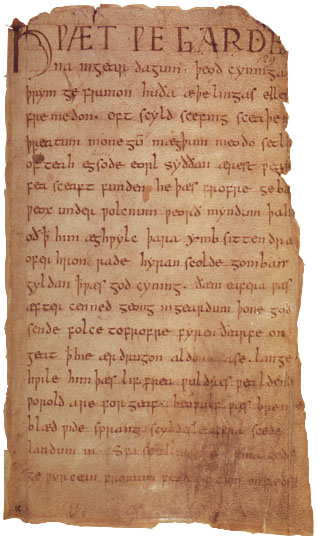

But there are complications. For one thing, when there is only one manuscript, one is entirely dependent upon that manuscript. There is nothing to fall back on if the manuscript is illegible. And this can be a severe problem. Taking the case of Beowulf, the only surviving manuscript was burned in the Cotton Library fire, and is often illegible. So we are largely dependent on two transcripts made some centuries ago, both of which have problems of their own. Other manuscripts may present equivalent or even greater difficulties. The manuscript may be a palimpsest. Or it may use a non-standard orthography. In a handful of instances we may not even be able to read the script of the original (e.g. the Greek Linear A writings, but also some Persian inscriptions and even Old English writings in odd forms of the runic alphabet.) Thus it is more likely, in the case of a single-copy text, that the scholar will have to pay particular attention to the seemingly simple task of just reading the manuscript. The second problem of texts preserved in a single copy is that we have no recourse in the event of an error. If a Biblical manuscript has lost a line, we can determine its reading from another copy. But if the ancestral copy of the Antigone has lost a line (and we can tell that it is missing because the surrounding lines make nonsense), how can we correct it? I use this as an example because this is a case where we can show this happened; the text of Antigone 1165-1168 makes nonsense in all the manuscripts. We know the correct reading only because Eustathius's commentary preserves the missing line. In the case of multiple manuscripts, even if all of them have an error, the nature of the mistakes may tell us something about the original. Not so when there is only one copy. | The sole manuscript of Beowulf, Cotton Vitellius A.xv. The first

page of the poem. The photograph, digitally adjusted to increase

legibility, still shows the scorch marks at the bottom of the page;

the outer margin has also been eaten away by the fire, with some

loss of text (corrections in []). For a better view of the actual manuscript,

see the British Library site; there it an image

here.

The first seven lines of the text read as follows (the

*, equivalent to a raised point in the Old English, indicates the end

of a metrical line; these are not always marked in the manuscript; where

they are not, {*} is used; suspended letters are spelled out. The word division

matches the manuscript as I read it, though modern editions consider this defective):

HWÆT WE GARDE |

Thus the task of editing a book preserved in only one manuscript is arguably the most complex and difficult in textual criticism, for the scholar must reconstruct completely wherever the scribe has failed. We have already seen that these manuscripts often need vast numbers of emendations. They also require particularly clever ones.

There is a minor variation on this theme of emendation in the case of works which exist in only one manuscript, but for which we also have epitomes or other works based on the original source. (An example would be the portions of Polybius which overlap the surviving portions of Livy. Livy used Polybius, often quoting him nearly verbatim but without identifying the quotations.) These secondary sources can supply readings where the text is troubled. However, since the later sources are often rewritten (this is true even of the epitomes), and may be interpolated as well, it is usually best to use them simply as a source for emendations rather than to use them as a source of variant readings.

This theme has a variation in the case of editions copied from other editions: This applies in the case of Malory above, and also some of Shakespeare's plays, where we have two semi-independent editions. Caxton surely consulted British Library Add. 59678, but he must have consulted something else, too, even if it was only his own head. In the case of Shakespeare, we can take A Midsummer Night's Dream as an example: There are two texts, the quarto (properly, the first quarto, but the second quarto was copied from the first quarto and is not an independent witness) and the folio, copied from the second quarto but with corrections seemingly from an authoritative second source. The interesting question here, then, is how authoritative is the text in the places where our two sources agree: Does this agreement have as much strength as an instance where two genuinely separate sources agree (meaning that we trust the joint reading as much as a reading supported by two different manuscripts), or is it a case where one corrector or another didn't notice a divergence? This question, unfortunately, has no simple answer -- but one need to bring it up and be aware of the problem.

Another variation is the criticism of inscriptions. Although an inscription is, of course, the original inscription, it is not necessarily the original text. When Darius I of Persia ordered the making of the Behistun inscription, he certainly didn't climb the rock and do the carving himself -- rather, he composed a message and left it to the workers to put it on the rock. Thus the inscription will generally be a first-generation copy of the original. This is still much better than we expect for literary works -- but it is not the original.

Still another variation is the Gilgamesh Epic. This exists in multiple pieces, recensionally different, in multiple languages, from multiple eras, with some of the later versions incorporating material originally separate, and not one of the major recensions is complete. Here one has to step back from the problem of deciding how to reconstruct and first settle what to reconstruct.

Books Preserved in Multiple Manuscripts

This is the case for which Lachmann's technique is best suited. It is ideal for traditions with perhaps five to twenty manuscripts, and can be used on larger groups (though it is hardly practical if there are in excess of a hundred manuscripts).

We begin, of course, with recensio. This can have three possible outcomes:

- All manuscripts are descendents of a single manuscript, which survives. In this case we simply turn to that manuscript, and proceed to subject it to examinatio and emendatio.

- All manuscripts are descendants of a single manuscript now lost. In this case we reconstruct the archetype (this will usually consist simply of throwing out errors, since all the manuscripts have a recent common ancestor), and proceed as above, subjecting this reconstructed text to examinatio and emendatio.

- The manuscripts fall into two or more families. In this case, we proceed through the full process of selectio, examinatio, and emendatio.

Books Preserved in Hundreds of Manuscripts

This is an unusual situation; very few ancient works are preserved in more than a few dozen manuscripts. But there are some -- Homer being the obvious example. (Another leading example, the Quran, is rarely considered as a subject for textual criticism. At least one major edition of the Quran, in fact, was not even taken from manuscript; it was compiled by comparing the recitations of 20 or so Quranic scholars. The primary tradition of the Quran is considered to be oral, not written.) The Iliad, which is preserved in somewhat more than 600 manuscripts, is believed to be the most popular non-religious work of the manuscript age. (Of course, it should be noted that the works of Homer were regarded as scripture by the Greeks -- but certainly not in the same way that the New Testament was regarded by Christians!)

In the handful of cases where manuscripts are so abundant, of course, the stemmatics used for most classical compositions become impossible. We have the same problem as we do with the New Testament: Too many manuscripts, and too many missing links. We are forced to adopt a different procedure, such as looking for the best or the most numerous manuscripts.

Since the methods used are fundamentally similar to those used for New Testament criticism, we will not detail them here. It is worth noting, however, that most critics consider the Byzantine manuscripts of Homer to be more reliable than the assorted surviving papyri. The papyri will occasionally contain very good readings -- but in general they seem to contain wild, uncontrolled texts. Whereas the Byzantine manuscripts reflect a carefully controlled tradition, presumably going back to the Alexandrian editors who standardized Homer.

This fact should not be taken to imply anything about New Testament criticism; the situations are simply not parallel. But it serves as a reminder that a late manuscript need not be bad, and an early one need not be good. All must be judged on their merits.

It should be noted that computers have been used to work on a stemma for Chaucer manuscripts, which number in the dozens if not in the hundreds. So there is hope that we will see stemma for texts such as Homer.

Books Preserved in Multiple Editions

| A special complication arises when books are preserved in multiple editions. This is by no means rare; an author would often be the only scribe available to copy his own work, and should he not have the right to expand it? (We may even see a New Testament parallel to this in the book of Acts, where some have thought that the author produced two editions, one of which lies behind the Alexandrian text and the other behind the text of Codex Bezae.) Even authors who were not their own scribes would often expand their work. The Vision of Piers Plowman, for instance, exists in three stages (perhaps even four, though the fourth is probably a prototype and was not formally published). The first stage, known as "A," is 2500 lines long, and does not appear to have been finished. Some years later the "B" text, of 4000 lines, was issued (this is the text most often published and is the basis for most modernized versions). A final recension, the "C" text (only slightly longer, but considered to be of poorer quality) followed a few years later. All were probably by the same author (though this is not certain), but it is believed that, in revising the "B" text to produce the "C" version, the poet used a manuscript that was produced by a different scribe. What became of the original copy of the "B" text is unknown; perhaps it was presented to a patron. | Near-contemporary but not really a witness: Piers the Plowman, the upper portion of folio 9 in Cotton Vespasian B.xvi (cited in critical editions as "M"). Thought to date from the late fourteenth century, which, since the "C" text dates from around 1385 and the author died within a year or two of that date, was copied within a generation of the author's death. But, since it is a revision of the "C" text, itself a revision of the "B" text, it tells us nothing useful about the "A" text shown in the stemma at left. Note how different this hand is from the Anglo-Saxon hands used for Beowulf and Wulfstan. Note also the elaborate use of coloured inks: the red dots to indicate line breaks, the red in the first letter of almost every line, the coloured first letters of sections, and the marginal squiggles which also mark section breaks. Finally, observe how very different is the hand scribbling in the margin. |

This also poses a problem for the scholar working on a stemma. The edition of the "A" text of Piers Plowman by Thomas A. Knott and David C. Fowler, for instance, gives the following stemma (somewhat simplified), with actual manuscripts denoted by upper case letters (sometimes with subscripts or two-letter abbreviations) and ancestors in lower case letters:

|----x-----V H

|

Archetype---|----y--|--y1----T H2 Ch D

| |

| |--y2----U R T2 A M H3

| |

| |--y3----W N Di

| |

| |--------I

| |

| |--------L

|

|----------------B text

Thus, for Piers Plowman, a later recension must be used as one of the three witnesses to the earlier recension -- a practice which, if we were to do it in another context, we would not call "reconstruction" but "contamination" (or, if we want to make it sound nicer, "harmonization").

Even more curious is the case of the Old English poem The Dream of the Rood, which exists in a long form, in the Roman alphabet, in the tenth century Vercelli Book, and in a much shorter form, in a runic script, inscribed on the eighth(?) century Ruthwell Cross. (In this instance it is not really clear what the relationship between the texts is.)

We could cite many other instances of works existing in multiple editions (e.g. Julian of Norwich; for that matter, we know that even Josephus issued multiple editions of his works). Indeed, there is a modern equivalent, even if I hate to mention it: Consider the movie, which often has a "studio cut" and a "director's cut." But citing examples is not our purpose here; our interest is in what we learn from these examples.

In addition to editorial work, multiple editions can come about as the result of ongoing additions to a document. This typically occurs in chronicle manuscripts. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, for instance, begins with a core created by King Alfred of Wessex (reigned 871-899). But from then on, the various foundations maintaining it kept their own records, often comparing the documents. In addition, a new foundation might make a copy of an older Chronicle then add its own additions (so, for example, with Chronicle MSS. A and A2). And, since the Chronicle was updated sporadically, it is theoretically possible for a manuscript to be "its own grandpa" -- the first part of A2 is copied from A, but later parts of A might (barely possibly) be derived at some removes from A2 or another lost descendant. To add to the fun, the manuscript A is in a different dialect of Anglo-Saxon from all other Chronicle manuscripts. The different recensions cannot be considered translations -- the dialects were still one language -- but adjustments had to be made to conform the text in one dialect to the idiom of another.

When multiple editions of a work exist, of course, it is not proper to conflate the editions to produce some sort of ur-text. The editions are separate, and should be reconstructed separately. The question is, to what extent is it legitimate to use the different editions for criticism of each other?

Although the exact answer will depend on the circumstances, in general the different editions should not be used to edit each other. (They can, of course, be used as sources of emendations.) They may be used as witnesses for one or another variant reading -- but one should always be aware of the tendency to harmonize the different editions.

Textual Criticism of Lost Books

At first glance, textual criticism of a lost book may seem impossible. And in most cases it is; we cannot, for instance, reconstruct anything of Greek tragedy before Æschylus.

But "lost" is a relative term. The "Q" source used by Matthew and Luke is lost, but scholars are constantly reconstructing it. The situation is similar for many classical works. Consider, for example, the Egyptian historian Manetho. We have absolutely nothing direct from his pen. So much of his work, however, was excerpted by Eusebius and Africanus (and sometimes by Josephus) that Manetho's work still provides the outline of the Egyptian dynasty list.

This is by no means unusual; many classical works have perished but have been heavily excerpted. Polybius is another good example. Of his forty-volume history, only the first five books are entirely intact (we also have a large portion of book six, and a few scattered fragments of the other books). But most of the information from Polybius survives in the writers who consulted him -- Livy and Diodorus used him heavily, and Plutarch and Pliny occasionally.

The problem in Polybius's case -- as in Manetho's -- lies in trying to determine what actually came from the original author and what is the work of the redactor. (We can perhaps grasp the scope of the problem if we imagine trying to reconstruct the Gospel of Mark if we had only Matthew and Luke as sources.) This is made harder by the fact that the redactors often introduced problems of their own. (A comparison of Africanus's and Eusebius's use of Manetho, for instance, shows severe discrepancies. They do not always agree on the number of kings in a dynasty, and they often disagree on the length of the reigns. Even the names of the kings themselves sometimes vary.)

Thus it is often possible to recover the essential content of lost books. However, one should never rely on the verbal accuracy of the reconstructed text.

There are variations on this theme. When the second part of Don Quixote was long delayed, an enterprising plagairist published a continuation in 1614. This was not an actual work of Cervantes (who published his correct continuation in 1615), but it thought to have been based at least in part on a manuscript Cervantes allowed to circulate privately. The result is at least partly genuine Cervantes -- but not something the author wanted published, and not entirely in his own words, either.

Other differences between Classical and New Testament Criticism

We have already alluded to several of the differences between Classical and New Testament criticism: The difference in numbers of manuscripts, the use of stemmatics, etc. There are other differences which much sometimes be kept in mind:

- The Age of the Manuscripts. Our earliest New Testament manuscripts

are very close to the autograph. Based simply on its age, it is theoretically

possible (though extremely unlikely) that

𝔓52 is the autograph of

the gospel of John. Certainly it is only a few generations away from the

original. Even the great uncials B and ℵ

are only a few centuries more recent than the autographs. Manuscripts

of the versions or their recensions may be even closer to the original -- as, e.g.,

theo of the Vulgate may have been prepared under the supervision of

Theodulf himself.

Such near-contemporary manuscripts are extremely rare for classical works (with the obvious exception of documents written in the few centuries before the invention of printing). While we often have very early manuscripts of classical works, they are still many years removed from the originals (e.g. the earliest manuscript of the pseudo-Hesiodic Shield of Heracles is P. Oxyrhynchus 689 of the second century -- a very early copy, but likely 500 or more years after the composition of the original). The problem is less extreme for some post-Biblical works (e.g. we have seventh-century manuscripts of Gregory of Tours, who wrote in the sixth century), but even these works usually exist only in very late copies. Related to this is: - The Possibility of an Autograph. Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae exists in some 200 copies (a sad testament to the tendencies of ancient scribes, since this is a piece of bad fiction disguised as history). The book was written probably shortly before 1140. Three copies are individually dedicated to Earl Robert of Gloucester (died 1147), who may have been Geoffrey's patron; to King Stephen (reigned 1135-1154), and to Stephen's close supporter Galeran of Meulan (died 1166?), respectively. Could one of these be the autograph? Or at least an autograph -- a copy in Geoffrey's own hand? The editions at my disposal don't say one way or the other -- but there is no obvious reason why it couldn't be so.

- The Evolution of the Language. Languages change with time, and manuscripts

can change with them. In Greek, the obvious example is the disappearance of the

digamma (ϝ).

We know that Homer used this obsolete phoneme, and Hesiod seems to have used

it as well (though it was less important by his time). But our extant manuscripts

do not preserve it. The scholar who reconstructs an early Greek text must therefore

be careful to note the possible effects of its disappearance.

This effect can also be seen, to some extent, in the New Testament (e.g. in the form of Atticising tendencies). However, the mere fact that the New Testament was the New Testament kept this sort of modernization to a minimum. (See also the next item.)

There are variations on this theme -- notably changes in the alphabet. Gregory of Tours records that the Frankish King Chilperic of the Franks attempted to add four new letters to the (Roman) alphabet, and ordered books written in the old alphabet to be erased and rewritten (HF V.44). This attempt at linguistic revision did not succeed -- but it may well have resulted in the destruction of important manuscripts and in less-accurate copies of others.

Something similar certainly happened with ancient Greek literature. In the early Classical period, there were numerous versions of the Greek Alphabet. Some of the differences were just graphical -- e.g. the Ionic alphabet used a four-stroke sigma (ᛊ) while the Attic used a three-stroke sigma (Ⰽ). But some were more significant: The Ionic alphabet had used the letter Omega, but the Attic didn't, and Corinth used M for the s sound. It wasn't until 403/2 B.C.E. that Athens formally adopted the Ionic alphabet, and some older writers probably continued to use the Attic alphabet for some time. Thus the earliest copies of most of the Greek tragedies, and very likely Homer and Hesiod as well, were originally written in alphabets other than the Ionic, and had to be converted. This means, first, that there could be errors of visual confusion in the text based on both Ionic and Attic forms, and second, that there could have been errors in translation between the alphabets.

The Semitic languages show another version of this: The addition of vowels. Each language added vowel symbols at different stages in its development, often imperfectly at first (e.g. Jacob of Edessa's system of Syriac vowels included only four symbols).

The illustration above shows a very simplified diagram of the evolution of most current alphabets. Solid lines indicate direct descent, dashed lines indirect descent. Any change in alphabetic form (including more minor ones such as changes in handwriting style, not shown here) will likely affect the history of the text of a manuscript. Above illustration adapted from page 255 of the article "The Early Alphabet" by John F. Healy in Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet. - Dialect and Spelling. It's quite certain that modern NT editions do not

use the actual orthography of the original autographs. However, there is a

recognized dialect and set of spelling rules for koine Greek. Thus, except in

the case of homonyms, there is no question of how to reconstruct a particular

word.

Not so in non-Biblical works! If the manuscripts are any indication, Chaucer did not use consistent spelling -- and even if he did, there were no conventions at the time, and his spelling would not match that of Gower or Langland or the Gawain-poet. Indeed, Chaucer and the Gawain-poet used dialects so different as to be almost mutually incomprehensible. And a particular copyist might personally speak a different dialect than the one used in the work he was copying, and so misunderstand or alter the text. We see this also in Herodotus, who evidently wrote in his own Ionic dialect with some ancient forms. In the manuscripts, however, we find forms "that it seems unlikely Herodotus could ever have written" (Concise Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, p. 265).

This imposes two burdens on the critic. First, there is the matter of properly reconstructing the original. Then there is the matter of orthography. Should one use the orthography in the manuscripts? Should one reconstruct the author's orthography (which may differ substantially from that found in the manuscripts)? Should one use an idealized orthography? An idealized dialect? What if the manuscript exists in two dialects (as, e.g., happens with most Old English works preserved in multiple copies)? There is no correct answer to this, but the student must be aware of the problem.

This can get really interesting when combined with the problem of different recensions. Piers Plowman, as noted above, exists in three recensions, all of which exist in multiple copies. But several of these manuscripts have been modified to conform to a particular dialect. It is possible, under certain circumstances, that the modifications in dialect could cause texts of different recensions to come closer together, which could confuse the manuscript stemma. (We see hints of this in the case of the Old Church Slavonic version as well, as this version has undergone steady assimilation toward the developing South Slavic dialects.)

In some traditions (particularly French literature) there has been a tendency to use dialects as a critical tool -- i.e., if a document exists in multiple dialects, then the manuscript(s) in the author's original dialect must be closest to the original. This may be true in some instances, but is far from assured. The manuscripts in the original dialect may have suffered severely in transmission, while one of the translated works may have been carefully preserved apart from that. Or the manuscripts in the original dialect may possibly have been subjected to double translation, in which case they are no guide to the original language. In neither case can we be sure of the value of manuscripts in the original dialect. - The state of the Early Printed Editions. For the New Testament, we have no real need to refer to either Erasmus's text or the Complutensian Polyglot, which are (for all intents and purposes) the only early editions. We have all of Erasmus's manuscripts. We don't know the manuscripts behind the Polyglot, but the text contains very little in the way of unusual readings. If these editions had not existed, we would be no worse off (indeed, given the regrettable influence exercised by the Textus Receptus, we probably would be better off if they had not existed). Not so with classical works! Early editions of Josephus seem to be based on manuscripts no longer known. Caxton's and Thynne's edition of Chaucer tend to represent witnesses which no longer survive -- usually not the best types, but not valueless, either. The case is similar for many other works. Scholars, therefore, should examine ancient editions with some care to see if they add to our knowledge.

- Books which Occupied More than One Volume. The New Testament, of course, is commonly divided into four separate sections, Gospels, Acts and Catholic Epistles, Paul, Apocalypse. These sections have separate textual histories, and sometimes even the books within the sections have separate histories. Because the books are relatively short, however, and were usually copied in codex form anyway, there are few if any instances of Biblical books being subdivided and the individual sections having separate textual histories. Here again the rules are different for non-Biblical documents. Many of the manuscripts of Josephus's Antiquities, for instance, contain only half the work -- and even those which contain both halves may be copied from distinct manuscripts of the two halves. The halves may well have separate textual histories. Scholars must be alert for such shifts.

- The Language of the Scribe. Most copies of the New Testament were made by scribes whose native language was Greek (usually Byzantine rather than koine Greek, but still Greek). There are exceptions -- L, Θ, and 28; also perhaps some of the polyglot manuscripts -- but these were exceptions rather than the rule. By contrast, most of our copies of Latin manuscripts were made by scribes whose native language was not Latin. They knew Latin -- but it was church rather than Classical Latin, and in any case it was a second tongue. So one should always be aware of the errors an Italian scribe, say, would make in copying a classical work (and be aware that a French or English or Spanish scribe might make different errors).

In addition, there were polyglot manuscripts. There is, for instance, the British Museum manuscript Harley 2253, containing items in French, Latin, and Middle English. The scribe clearly had familiarity with all three languages (by no means unusual for an educated English scribe around 1340), but there is no certainty that the scribe's copying methods or sources were the same for the three different languages. - The Conversion from Oral Tradition. The New Testament originated in written form, so it never had to make the painful transition from oral tradition to a written text. But other documents assuredly did -- and may have changed in the process. Homer is the most obvious example, but most languages have parallels, from Beowulf to the plays of Shakespeare (where the earliest printed editions seem to have been made from actors' memories) to Grimm's Fairy Tales. In a few cases, there was also the problem of inventing an alphabet to take down the tradition. Orally transmitted material is not transmitted in quite the same way as written (see the article on Oral Transmission). In addition, it leaves a textual problem: Does one attempt to reconstruct the version that was originally taken down, or the original oral composition (this is another of those unanswerable questions).

- The Need to Reconstruct from Fragments. We have many, many continuous manuscripts of the New Testament. If a new manuscript turns up, we need but fit it into the fabric of the surviving tradition.

This need not be so with classical works. We may well have multiple fragmentary manuscripts, with no complete copy to put the fragments in place.

Perhaps even worse is the case where we have a fairly complete copy, but with no indication of order. (This can happen, e.g., when a scroll is recovered from the wrappings of a mummy. It can also happen with a palimpsest, particularly if, as sometimes happened, the page numbers of the original writing were written in a coloured ink and did not adhere well to the paper.) - The problem of Spurious Additions. There is significant debate about doctrinal modifications of the text of the New Testament. However, it is generally conceded that, with the possible exception of the text of Codex Bezae and the lost New Testament of Marcion, the New Testament documents did not undergo significant rewriting. They were sacred, not to be modified.

Certain scribes felt free to modify classical texts, however. And if, as often happened, this modified text was the basis for all surviving copies, we have no ways to tell from the manuscripts that the passage is spurious. An obvious example is the famous reference to Jesus in Josephus (Antiquities XVIII.iii.3, or XVIII §63-64 in the Loeb enumeration). This passage cannot be original as it stands; it calls Jesus the Anointed -- and then spends three more sentences on him and ignores him thereafter. At the very least, the declaration of his Christ-hood must be spurious, and probably the whole passage. But it occurs in all manuscripts, and Eusebius was aware of it. So it is a very early insertion. Less certainly spurious, but even more difficult, is the ending of Æschylus's drama "The Seven Against Thebes." This drama comes to a logical tragic conclusion with the death of Eteocles -- whereupon we are presented with another 125 lines featuring Antigone, Ismene, and the Chorus. It is widely (though not quite universally) believed that this section -- over 10% of the play -- is spurious.

Normally we might say that it is not a problem for the textual critic. But this can be a problem. For instance, the Antigone/Ismene section of the Septem requires a third actor (the Herald/Messenger). This is the only portion of the Septem to use a third actor. Logic says that, had Æschylus been writing a three-actor play, he would have made better use of him than this! So if the final section is original, we need to examine the rest of the play to find a role for the third actor (keeping in mind that the speakers are not marked in the copies, only the change of speakers). This will affect our reconstruction of the play. (See the next point on Missing Elements.) - Missing Elements in specialized documents. A New Testament is complete in and of itself. It doesn't need anything except the text. But a drama, for instance, consists of more than just the text spoken by the actors. It also includes such things as stage directions and indications of who is the speaker. Our sources, however, often do not include such elements. This is true of the earliest Greek dramas (a change in speakers is marked with a special symbol, but the speaker generally is not indicated), but continues until quite recent times. Although the speakers are marked in the "Second Shepherd's Play" of the Wakefield Cycle of mystery plays, there are only four stage directions, in Latin; they are not sufficient to explain the action. This continues to be a problem, to a lesser extent, even in Shakespeare.

Once again, it is not the task of the textual critic to reconstruct the stage directions (which may never have been written down) or the speakers; that must be done after the text is established. But a knowledge of who is doing what can be essential in choosing between variants.

Stage indications are not the only thing which can be missing from a manuscript. Music is another obvious example. For poetry, there are also line and stanza divisions -- while printing poetry in this way is a modern invention, the line-and-stanza structure is ancient. And in non-metrical verse, it is not always obvious where line breaks fall. Correct reconstruction can be very important in cases such as Old English alliterative poems. If the line breaks are not correctly placed, one may not be able to tell which is the alliterating letter, meaning that errors can propagate for many lines and perhaps force bogus conjectural emendations. See also the item on Drawings and other non-textual contents. - Metrical or Other Poetic Corrections. Much of classical literature

is poetic, following particular conventions of metre and perhaps rhyme. If a scribe encountered a reading which appeared unmetrical (perhaps due to changes in the language;

see the section above), he/she might change it. Such a change, if done well,

may be indetectable -- but a poor change may require emendation. This requires

great sensitivity to the original author's style and dialect. (One should also

note that scribes may have been more sensitive to errors in metre or rhyme

than the authors they were copying.)

A special case of this is the so-called vitium Byzantium. Byzantine poetry resembled classical tragedy in using a twelve-syllable line. But the metre was different: The Byzantine poets were expected to place a stress on the penultimate syllable of a line, while the tragedians faced no such expectation. Scribes seem often to have adjusted the tragic texts to meet the Byzantine standard (possibly unconsciously). Even prose was somewhat affected by such conventions; sentence breaks in the Byzantine era were expected to be marked by several unstressed syllables. Thus we find many earlier works adjusted to meet these later stylistic rules.

Other rules may apply to poetry. For example, early poetic works in the Germanic languages used the alliterative metre -- each line consisted of four feet, each foot having a stressed syllable and varying numbers of unstressed syllables, with a slight pause (caesura) between the first two and the final two feet. At least two, and usually three, of the stressed syllables had to alliterate. But there were variations on this basic design. Some poems required more exact numbers of syllables. Other had more precise alliteration schemes (e.g. one scheme might allow only two syllables to alliterate, one on each side of the caesura, while stricter schemes might not only require three stressed syllables but require a pattern such as aa/ax). A scribe used to one particlar alliterative style might conform a work in a different style. - Corrections of offensive passages. A Christian scribe might well

regard the works of, say, Aristophanes or Ovid as obscene. There was doubtless

a temptation to bowdlerize.

Evidence of this happening is surprisingly slight. We do not find cleaned-up copies of Aristophanes. This trend seems to be more modern. But there are copies of Herodotus which omit an account of sacred prostitution (I.199). So if there are two major traditions, and one contains an account of something sexually explicit or offensive, while the other omits it, chances are that the account which includes it is original. - Drawings and other non-textual contents. A geometrical treatise

obviously could be expected to contain pictures. And such a drawing, unlike

a picture, could contain text. (It might also contain line segments which would

extend into the text, and affect its meaning -- e.g. by crossing an omicron

and turning it to a theta, though this is not very likely.) These captions

could sometimes wander from the drawing into the text. Much the same is true

of a work on geography if it contained maps. There is also the

problem of assuring an accurate rendering of the original drawing -- a

task where the rules of textual criticism are less applicable. (The whole